As a team member of the first MUAFS season 2018/2019 responsible for magnetic investigations I would like to introduce the geophysical methods used for archaeological purposes. These methods will also be highly relevant for the DiverseNile project.

In the last decades, geophysics became a substantial part of archaeological projects. Depending on several factors, the most suitable geophysical method is chosen: the environment (desert, steppe, swampland etc.), the archaeological period and the used archaeological materials (stone, mudbrick etc.), but also the questioning (settlement layout and extension, cemetery detection etc.). Additionally, the decision is influenced by available time, financial means and sometimes the season.

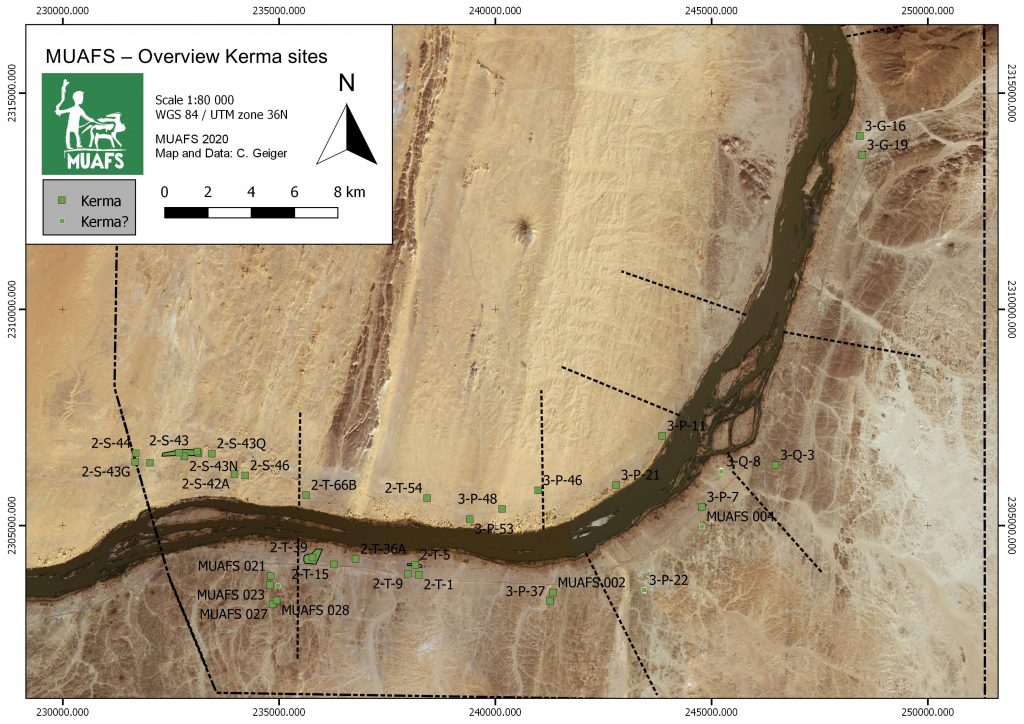

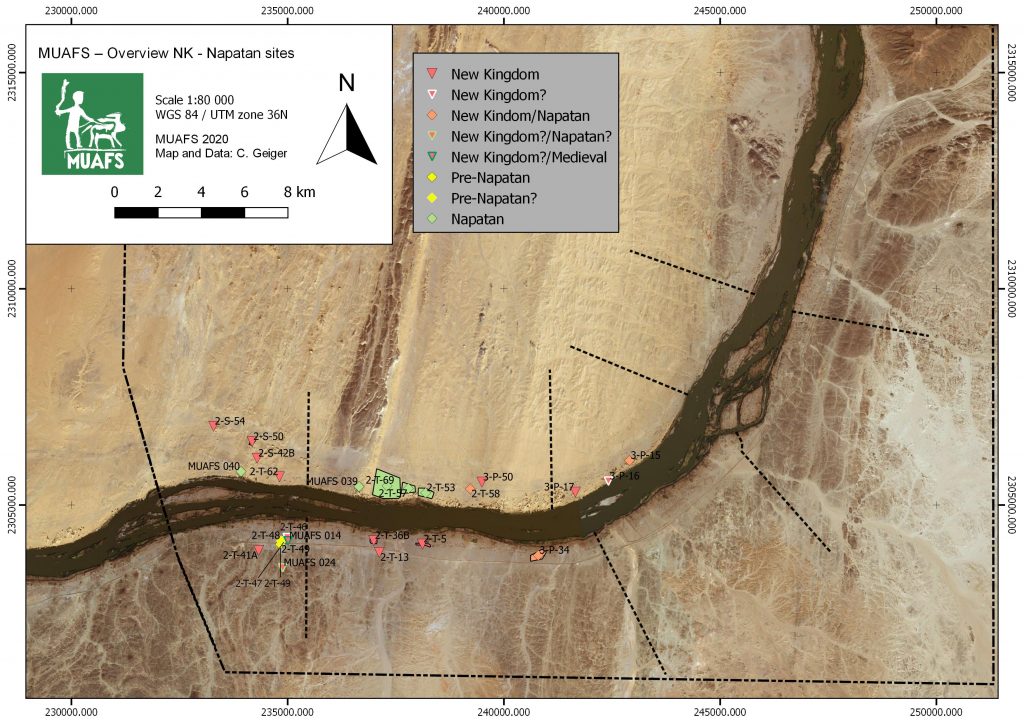

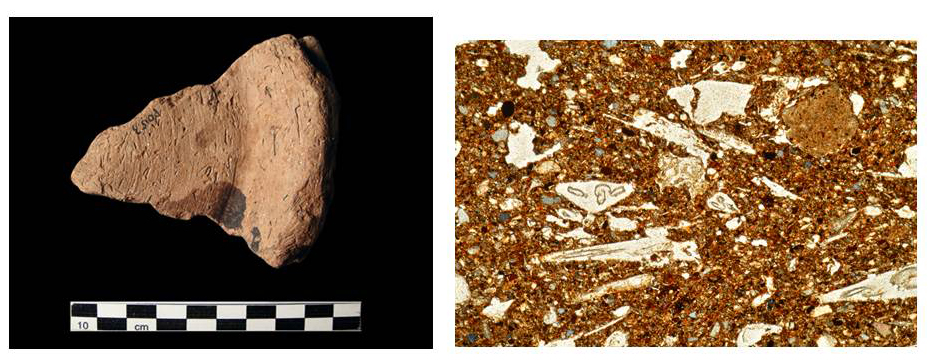

Still the fastest and most effective geophysical method in archaeology is magnetometry. It provides getting an overview of a site as well as its environment, extension and layout. Magnetic prospecting enables us to distinguish between settlement and burial sites, their structure, special buildings, open areas, as well as fortifications. Depending on the chosen sensors, we can learn more about the geology and environment and their changes over time. Accompanying measurements of magnetic susceptibility deliver information about magnetic properties of scattered objects and building materials as well as archaeological sediments and can be used in archaeological excavations as well.

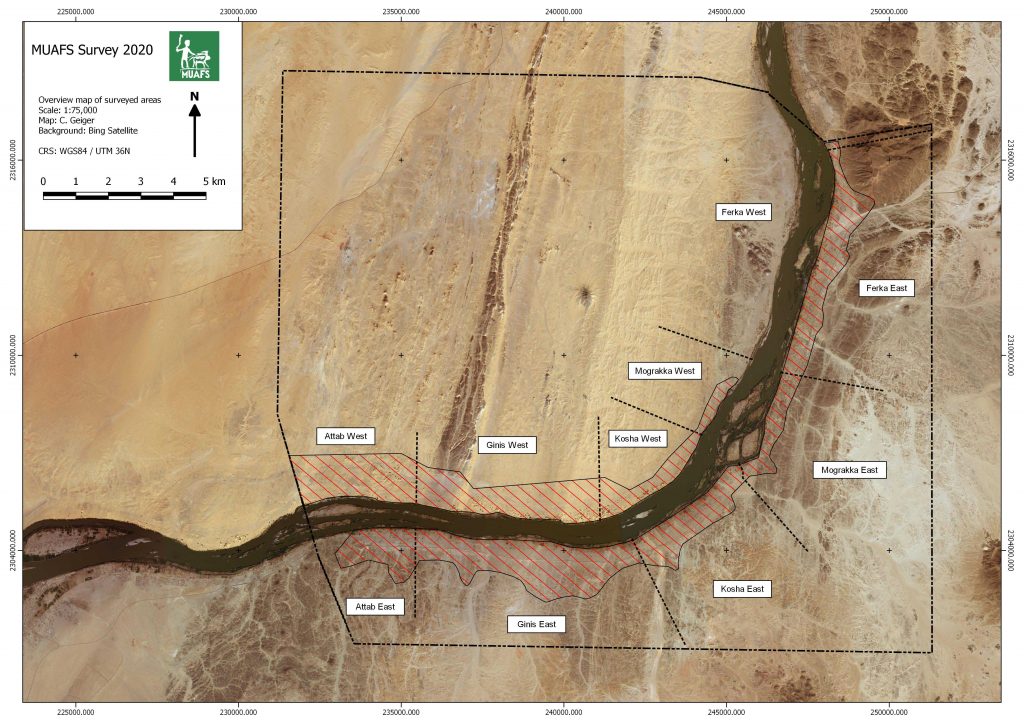

But how does it work? Magnetometers are recording the intensity of the earth magnetic field with high-resolution. Nowadays, the earth magnetic field in the Attab to Ferka region has an intensity of around 39.400 Nanotesla (nT). With sensitive total field magnetometers, magnetic anomalies of less than 1 nT can be detected during archaeo-geophysical surveys, displaying even archaeological features like mudbrick walls or palisades.

Magnetic investigations benefit from varying magnetic properties of archaeological soils and sediments as well as materials. Every human activity regarding the surface is detectable because of different magnetic response. For example, digging a ditch, building a wall or using a kiln is changing or disturbing the actual earth magnetic field. What else can be detected? Architecture, streets, canals and riverbeds, ditches, pits and graves can be revealed just as palisades, posts and fire installations. Additionally, more information about geological and environmental conditions can be collected using magnetometry, e. g. paleo channels or former wadis.

For detecting stone architecture and for example voids, resistivity (areal or profile) and Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) methods are applied, partly in addition to magnetic investigations. While magnetometry gives an overview about buried features beneath the surface in a ‘timeless picture’, GPR and ERT (Electrical Resistivity Tomography) provide more information about the depth and preserved height of the features. Of course, more than one geophysical method can be applied to get a comprehensive dataset for more complete interpretation of the results. Combined with archaeological work – survey and excavation – we can increase our knowledge and understanding of physical properties of archaeological and geological features as well as improve our interpretation.

Geophysical prospecting was originally developed for military purposes to detect submarine boats, aircrafts or gun emplacements. Furthermore, natural and especially mineral resources can be located. Geophysical methods and first of all magnetometry are used in archaeology since the late 1950s, when Martin Aitken detected Roman kilns in the UK. In Sudan, magnetometry is used since the late 1960s when Albert Hesse started investigations at Mirgissa in Lower Nubia. Since then, instruments as well as software programs for data collecting, processing and imaging have been developed and improved and offer detailed mapping of sites. First, geophysical prospecting can be applied fast, nondestructive and comprehensive. For magnetic prospection there is a variety of configurations to use, from handheld one/two-sensor instruments to motorized and multisensory systems but also different types of sensors. Through geographic information systems (GIS) geophysical investigations are benefiting from integrating high-resolution satellite images, drone images and models, survey and excavation data for a comprehensive interpretation of results.

After collecting magnetic data in the field, the files are downloaded and processed to get an idea of the first results. With that the field measurement proceeding can be adjusted as well as excavation trenches can be chosen. The detailed processing and analyzing of the collected field data are conducted back home on the desk.

References

Campana, Stefano; Piro, Salvatore (eds.) (2009): Seeing the Unseen. Geophysics and Landscape Archaeology. London: Taylor & Francis.

Dalan, R. (2017): Susceptiblity. In: Allan S. Gilbert, Paul Goldberg, Vance T. Holliday, Rolfe D. Mandel and Robert Siegmund Sternberg (eds.): Encyclopedia of Geoarchaeology. Dordrecht: Springer Reference (Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series), 939–944.

Fassbinder, Jörg W. E. (2017): Magnetometry for Archaeology. In: Allan S. Gilbert, Paul Goldberg, Vance T. Holliday, Rolfe D. Mandel and Robert Siegmund Sternberg (eds.): Encyclopedia of Geoarchaeology. Dordrecht: Springer Reference (Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series), 499–514.

Herbich, Tomasz (2019): Efficiency of the magnetic method in surveying desert sites in Egypt and Sudan: Case studies. In: Raffaele Persico, Salvatore Piro and Neil Linford (eds.): Innovation in Near-Surface Geophysics. Instrumentation, Application, and Data Processing Methods. First edition. Amsterdam, Oxford, Cambridge: Elsevier, 195–251.

Schmidt, Armin; Linford, Paul; Linford, Neil; David, Andrew; Gaffney, Chris; Sarris, Apostolos; Fassbinder, Jörg (2015): EAC Guidelines for the Use of Geophysics in Archaeology. Questions to Ask and Points to Consider. Namur: Europae Archaeologia Consilium (EAC Guidelines, 2).