November is usually one of the busiest months of the year. This holds especially true when one has just returned from fieldwork in Egypt and even more since some conferences are now organised as hybrid events, allowing in person attendance.

Though it will be quite a challenge, I am extremy grateful to have been invited to two events in the next days of which the topics are very close to my special fields and also to WP 3 Material culture of the DiverseNile project.

Today, I will be heading towards Mainz in Germany. Tomorrow and on Saturday the international workshop „Excavating the extra-ordinary 2. Challenges & merits of working with small finds“ will take place.

My own presentation on Saturday has the title: „What makes a pottery sherd a small find? Processing re-used pottery from settlement contexts“.

Re-cut pot sherds are among my favourite small finds and they occur in great numbers at domestic sites in both Egypt and Sudan (e.g. Qantir, Elephantine, Amarna and Sai Island). As multi-functional tools they attest to material-saving recycling processes.

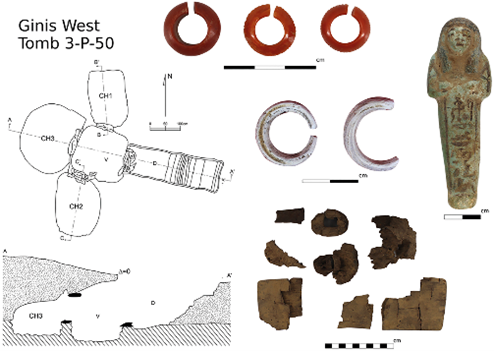

Re-used pottery sherds offer many intriguing lines of research, first because of the recycling process and questions related to objects biographies. Second, the multiple function of tools created from re-cut sherds allows to investigate diverse sets of tasks and practises in settlement contexts. Third, lids and covers created from pottery sherds illustrate the blurred boundaries between categories of finds in the archaeological documentation, especially between ceramic small finds and pottery. Lids are also commonly part of ceramic typologies when produced as individual vessels. Can we determine if it made a difference to the ancient users whether a lid was made from a re-used sherd or as a new vessel? I will use the nice example of a complete Kerma vessel found with a stone lid in situ in one of our tombs in cemetery GiE 003 as case study to discuss these points.

My lecture in Mainz mainly aims to address some terminological and methodological issues arising from processing re-used pottery sherds as small finds as well as dating problems. I will outline the recording procedure established in the framework of the ERC AcrossBorders project for New Kingdom Sai and how we have adapted this workflow for the ERC DiverseNile project.

On Sunday, I will be heading to Cairo for the next event, the conference “Living in the house: researching the domestic life in ancient Egypt and Sudan”. The conference is organized by Dr. Fatma Keshk on behalf of the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale and the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Research Center in Cairo. The main focus of this event is settlement archaeology in its multi- and interdisciplinary aspects in ancient Egypt and Sudan. Chloe will also join the conference and we are expecting much input for the DiverseNile project, especially WP 1, settlements.

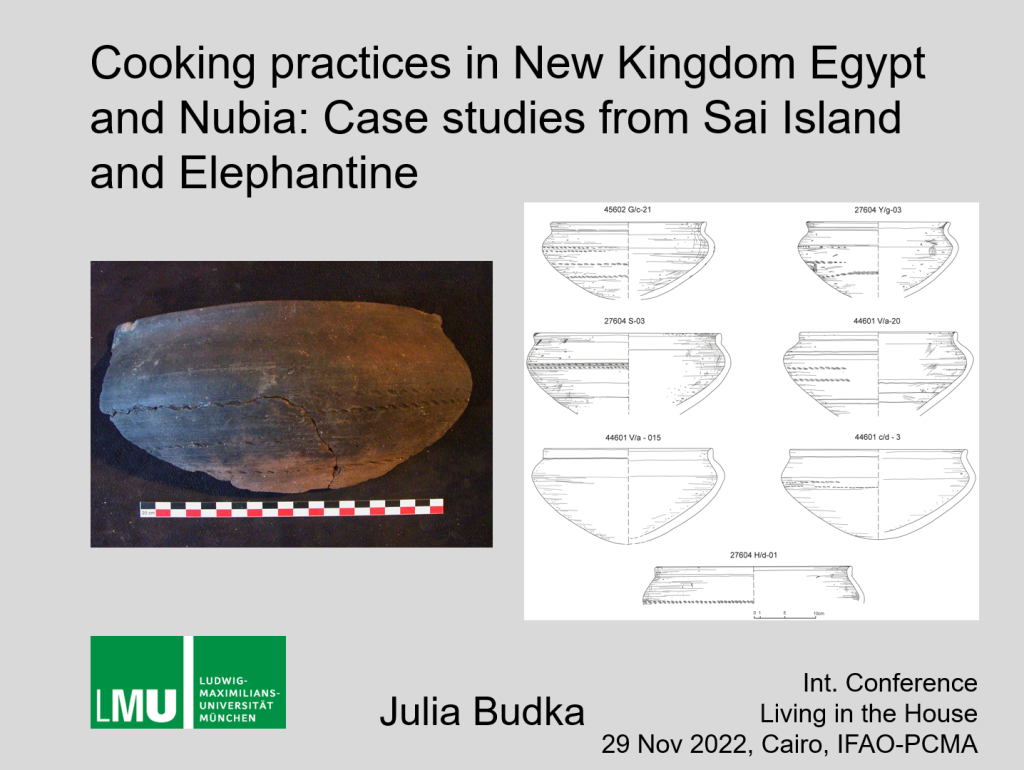

At the “Living in the house” conference, my lecture on Monday will again focus on ceramics, but this time on cooking ware.

I will present some results from the ERC Project AcrossBorders comparing cooking practices in two contemporaneous sites of the New Kingdom, Elephantine in Egypt and Sai Island in Nubia. I will also show a few examples from the MUAFS concession and how they fit to the other evidence. Preliminary results from organic residue analysis from Egyptian-style and Nubian-style cooking pots allow us to ask questions about diet and culinary traditions. My aim is to illustrate that dynamic and diverse choices within the New Kingdom reflect a high degree of cultural entanglement and challenge previous assumptions, for example of the role of Nubian cooking pots as cultural markers.

I am very much looking forward to these two workshops and especially the exchange and discussion with many colleagues.