Uncovering the origins of the sandstone used in the construction of ancient monuments offers a unique glimpse into the interplay between natural resources as well as human craftsmanship and interaction. On Sai Island, nestled in the Nile between the 2nd and 3rd cataracts in Northern Sudan, lies Temple A, an 18th Dynasty Egyptian structure. The sandstone used in its construction, sourced from the island’s abundant deposits, has long piqued the curiosity of archaeologists and geologists alike. A recent study delves into the mineralogical and geological characteristics of these sandstones, seeking to uncover their precise origins and the choices made by ancient builders.

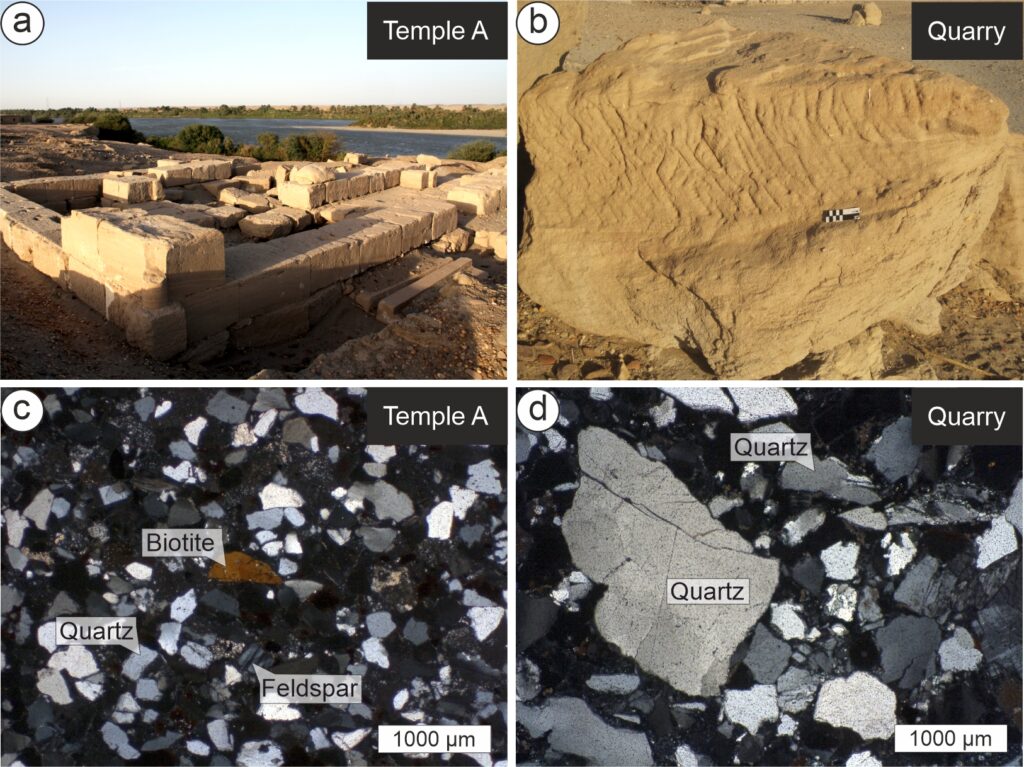

The investigation centered on sandstone samples taken from Temple A, and three nearby quarries. Using advanced analytical tools such as polarization microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and micro-Raman spectroscopy, we were able to analyze the stones in detail. The sandstone clasts were found to be composed predominantly of quartz, making up 90–95%, with minor contributions from feldspar and lithoclasts. Clay minerals like kaolinite and illite were present in varying amounts, forming part of the stone’s matrix. The stones also contained traces of iron-titanium oxides, which had undergone alterations over time due to natural chemical processes.

The study revealed that the sandstone used in Temple A was more finely sorted and contained smaller grain sizes compared to the samples from the quarries (Figure 1a-d). This finding suggests that the builders deliberately selected stones with uniform characteristics to ensure consistency in the temple’s appearance. The lighter color and moderate sorting of the temple sandstone contrast with the darker, poorly sorted stones found at the quarry and outcrops. This selective quarrying points to a sophisticated understanding of the properties of building materials and a meticulous approach to construction.

However, determining the exact source of the sandstone used in Temple A proved challenging. Despite the similarities in composition between the temple stones and the natural occurrences, the analysis could not definitively link the building materials to a specific quarry. We suggest that the stones likely originated from the same geological formation but does not rule out the possibility of multiple extraction sites within the island.

The presence of minerals such as kaolinite and illite in the sandstone’s matrix provided further insights into the geological history of these rocks. These minerals form under specific environmental conditions and suggest that the sandstone underwent stages of weathering and burial over geological time. Iron-titanium oxides, including ilmenite and its altered forms, indicated processes of chemical transformation as the stones interacted with water and other environmental factors. These transformations reflect the dynamic geological history of Sai Island, where tectonic forces and sedimentary processes shaped the materials long before they were quarried for use in ancient architecture.

While the exact quarrying practices remain unclear, the findings underline the care and intentionality that went into selecting construction materials. The builders of Temple A seemed to prioritize not only structural integrity but also the aesthetic qualities of the stone.

The study of the sandstone from Sai Island is a window into the decisions and practices of colonial Egypt in Nubia during the New Kingdom. Through understanding the material choices of the past, we gain a greater appreciation for the deep relationship between humanity and the natural world. Further investigations, including detailed geological mapping and isotopic analyses, could reveal even more about the origins of these stones and the history they carry.

Sai Island’s sandstone is more than a building material—it is a testament to the resourcefulness and artistry of its ancient inhabitants. Each grain of sand holds a story, shaped by eons of natural forces and, ultimately, by human hands. By unraveling these stories, we not only connect with the past but also deepen our understanding of the intricate connections between geology, culture, and time.