Recently, I happened to have a conversation with a group of friends and colleagues who come from different parts of the world about the meaning and the various cultural and ontological implications of the question “Where are you from?”.

In seven years, that I have lived abroad, working in an international team, my way to approach and answer this question has perhaps changed as my point of view on the concepts of identity, nationality, and ethnicity which compound the complexity of us as humans.

Certainly, asking someone “Where are you from?” opens a multitude of different and equally acceptable answers. Most of us will reply indicating the place from where they were born providing to the interlocutor as many details on their specific provenance (state, region and even city) as they want to affirm and communicate their roots. Others will possibly prefer to answer with the place they currently live as this information might better fit with their actual perception of cultural identity.

Not by chance, these arguments are closely related to the work I am doing within our DiverseNile project and particularly, in my case, as specialist in provenance and technological studies on pottery, with the significance of materiality – and ceramic objects – for addressing questions on contact space biographies, cultural identity and encounters.

In our times, objects and goods mostly carry with them labels that inform us about the place of manufacture and from where their design come from (i.e., Designed in X, Made/Manufactured in X). These claims are regulated and controlled according to rules established by National and International commissions. Hence, the acronym COO stands for “Country of Origin” and represents the country or countries of manufacture, production, design, or brand origin where an article or product comes from (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Country_of_origin). A document called certificate of origin will then authenticate that the product sold or shipped was manufactured in a particular country (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Certificate_of_origin).

In the past such labels did not exist. However, already in the late Predynastic period in Egypt (c. 3000 BCE) markings of vessels appeared as well as sealings on jar stoppers which refer to the provenance and owner of the contents (cf. e.g. Engel 2017). Markings of objects, especially amphorae, were more common in the Second Millennium BCE giving us information about the provenance and owners of the content as well as places of manufacture. However, most of the ceramic vessels intended for private use was not “registered”. Hence, the main task of ceramologists and archaeometrists consists in investigating on (and decoding) the place/s of origin and manufacture of ceramic objects, by means of the differentiation and classification of their characteristic stylistic, morphometric, technological, and compositional features.

Perhaps the concepts itself of provenance and origin of an object comprise several acceptations. First, there is the provenance/s of the raw materials (which in the case of ceramics includes both the clay raw materials and tempers), in the second instance, the place of manufacture, then the place (or places) of use of the object, and lastly that of discard (which might differ from that of use). To this list are added all the information concerning the “provenance” and “cultural identity” of the potter who produced the vessel and those regarding the people who used and discarded that object.

Overall, the notion or idea of “identity” includes many areas that are still unexplored or that would otherwise require a thorough discussion. For many years, both in the field of archaeology and cultural anthropology, static and crystallized visions of identity have unfortunately dominated. Identities were often perceived as if they are closed monothetic entities or categories without reciprocal and fluid relations with the others. Recently, we have witnessed attempts to lighten such positions, through what could be defined as a deconstruction of the ontology of identity. Remarkably interesting, in this respect, is an essay by the cultural anthropologist Remotti (2010). He believes that the concept itself of “identity” can be dangerous as it might represent a kind of (artificial) opposition between “us” and the “others”.

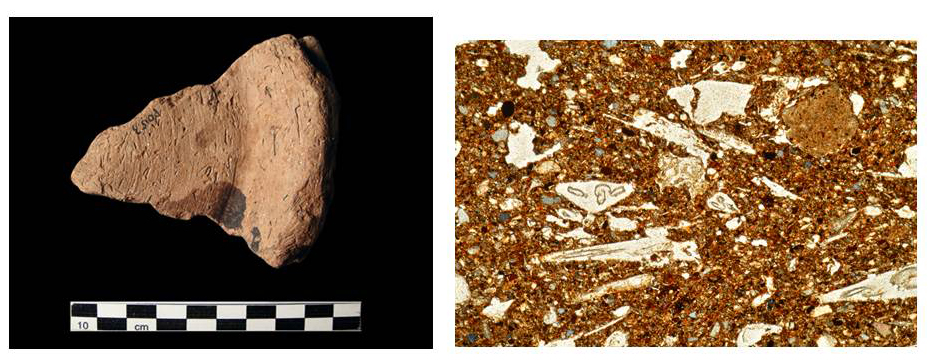

The case study of Sai Island (as well as other central Egyptian towns in Nubia) (see e.g. Budka 2018; Carrano et al. 2009; D’Ercole and Sterba 2018; Ruffieux 2014; Spataro et al. 2015) has shown the interesting coexistence in the archaeological record of Egyptian-style objects produced with Nubian raw materials (we would now say Designed according to the Egyptian-style and Made in Nubia), objects produced entirely according to the Nubian style in Nubian raw materials (Designed and Made in Nubia), imported Egyptian objects (Designed and Made in Egypt) and also hybrid products (Designed in a mixture of Egyptian and Nubian style and Made in Nubia). So-called hybrid pottery types are however difficult to separate from the first category of Egyptian-style objects.

The autoptic stylistic and morphological classification of pottery together with the chemical and technological laboratory analyses carried out on selected samples are fundamental tools to access this information. However, while the compositional data relating to the origin of the clay raw materials is in all respect’s objective and quantifiable (values and proportions of specific diagnostic major, minor and trace chemical elements), the visual stylistic and technological information are more ephemeral and critical to access.

O. Gosselain (2000: 193) stated that “Decoration belongs to a category of manufacturing stages that are both particularly visible and technically malleable, and likely to reflect wider and more superficial categories of social boundaries. Fashioning, on the other hand, constitutes a very stable element of pottery traditions and is expected to reflect the most rooted and enduring aspects of a potter’s identity”. Hence, decoration, more than technological behaviours and manufacturing choices, is a fairly permeable category, susceptible to change and innovation (Gosselain 2010). This is well traceable in the decoration of Egyptian ceramics which partly adopted Nubian ways of decoration. Differently, a change and contamination in the technological and manufacturing stages of pottery (e.g., surface treatment, forming/fashioning) often indicates a stronger and deeper level of cultural communication and social transmission. In this respect, the so-called hybrid Egyptian-Nubian products from Sai and elsewhere perfectly embrace the extraordinary complex and intertwined dynamics of cultural encounter between Nubians and Egyptians in New Kingdom Nubia.

The main purpose of my work task within the DiverseNile project is the understanding of these dynamics through a scientific and objective analysis of the various identity codes and “provenance attributes” of the ceramic objects found in the area between Attab to Ferka, and their comparison with the pottery corpus of the central sites like Sai. Also, it is possible that the categories themselves of “provenance”, “identity” and “cultural belonging” will be re-calibrated and newly shaped according to a new and more fluid vision of the materiality of the human culture. Possibly, when asked “Where you come from?”, objects will then surprise us with a new range of answers.

References

Budka, J. 2018. Pots & People. Ceramics from Sai Island and Elephantine, 147–170, in: J. Budka and J. Auenmüller (eds.), From Microcosm to Macrocosm. Individual households and cities in Ancient Egypt and Nubia, Leiden.

Carrano, J.L., Girty, G.H. and Carrano, C.J. 2009. Re-examining the Egyptian colonial encounter in Nubia through a compositional, mineralogical, and textural comparison of ceramics. Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 785–797.

D’Ercole, G. and Sterba, Johannes H. 2018. From Macro Wares to Micro Fabrics and INAA Compositional Groups: The pottery corpus of the New Kingdom town on Sai Island (Northern Sudan), 171–184, in: J. Budka and J. Auenmüller (eds.), From Microcosm to Macrocosm. Individual households and cities in Ancient Egypt and Nubia, Leiden.

Engel, E.-M. 2017. Umm el-Qaab VI: Das Grab des Qa’a, Architektur und Inventar. Mit einem Beitrag von Thomas Hikade. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 100. Wiesbaden, Harrassowit.

Gosselain, O. 2000. Materializing identities: an African perspective. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 7, 187–216.

Gosselain, O. 2010. Exploring the dynamics of African pottery cultures, 193–226, in: R. Barndon, A. Engevik and I. Øye (eds.), The Archaeology of Regional Technologies: Case Studies from the Palaeolithic to the Age of the Vikings. Edwin Mellen Press, Lampeter.

Remotti, F. 2010. L’ossessione identitaria. Laterza, Rome.

Ruffieux, P. 2014. Early 18th Dynasty Pottery Found in Kerma (Dokki Gel), 417–429, in: J.R. Anderson and D.A. Welsby (eds.), The Fourth Cataract and Beyond. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies, British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 1, Leuven.

Spataro, M., Millet, M. and Spencer, N. 2015. The New Kingdom settlement of Amara West (Nubia, Sudan): mineralogical and chemical investigation of the ceramics. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 7.4, 399–421.