The post-excavation processing of the Kerma cemetery GiE 003 is in full swing (see also an earlier blog post). There are some interesting observations regarding the diachronic development of the site and also its spatial organisation. A case study on the latter is presented below.

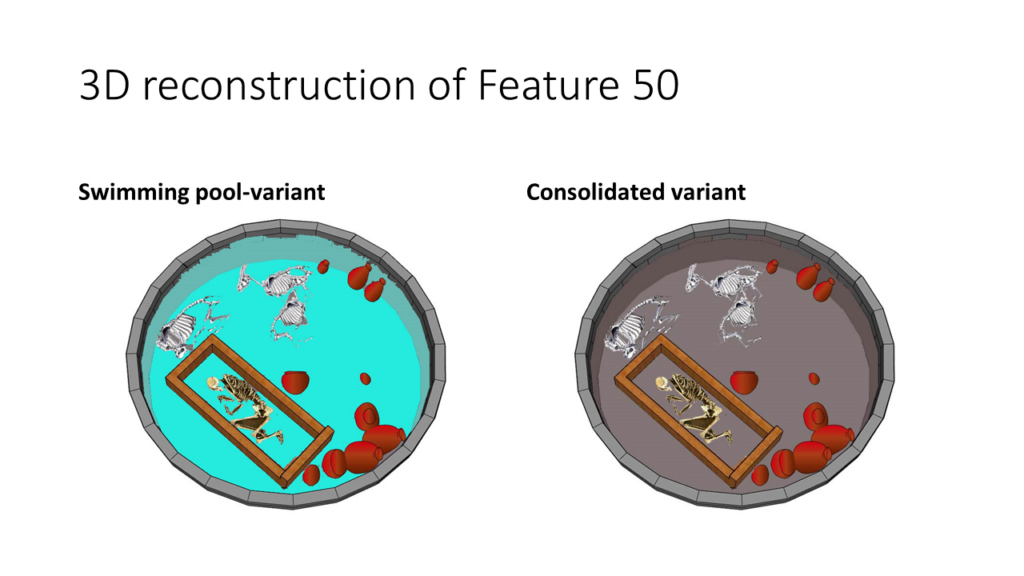

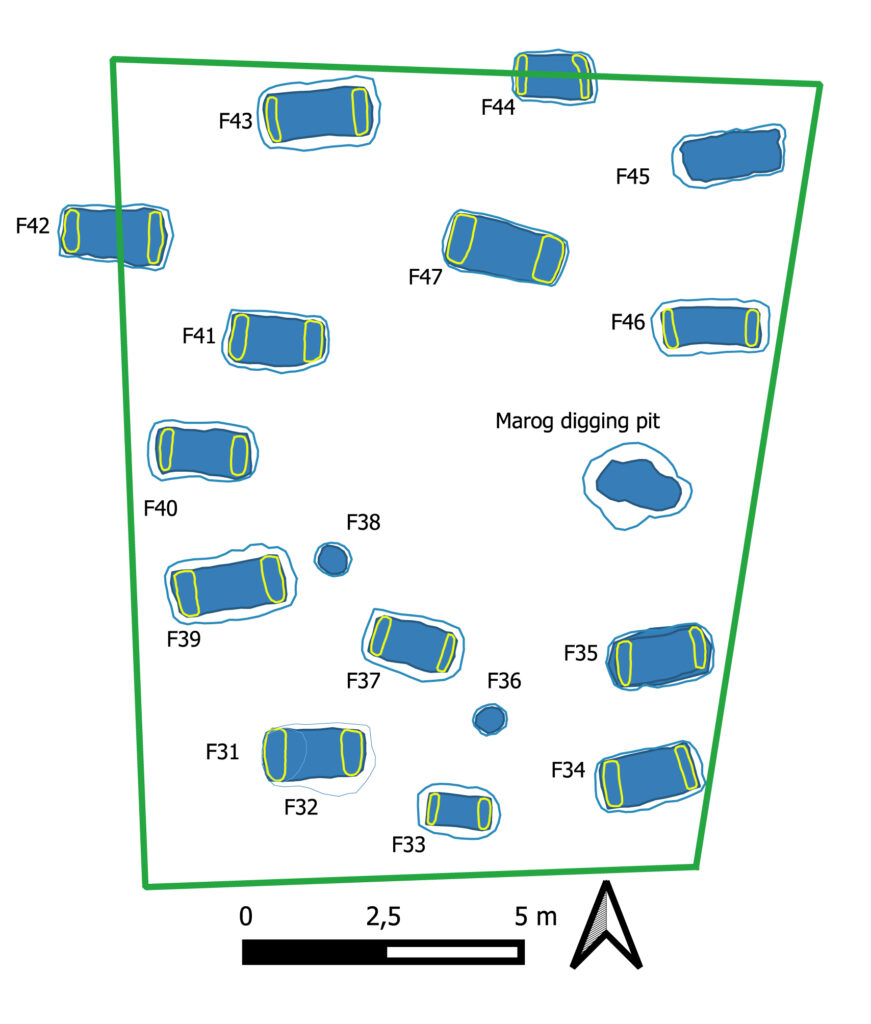

Trench 3 excavated in GiE 003 yielded Classic Kerma burial pits (Budka et al. 2023, Budka 2024). The trench is situated in the northwestern extent of our excavations at the site. It shows a relatively large area on its eastern side in which no burial pits were found. This apparent ‘gap’ contrasts with the surrounding areas, which show dense burial activity and graves laid out very regularly in the same orientation. Such a deliberate avoidance of this area raises some questions about ceremonial practices associated with the cemetery’s use.

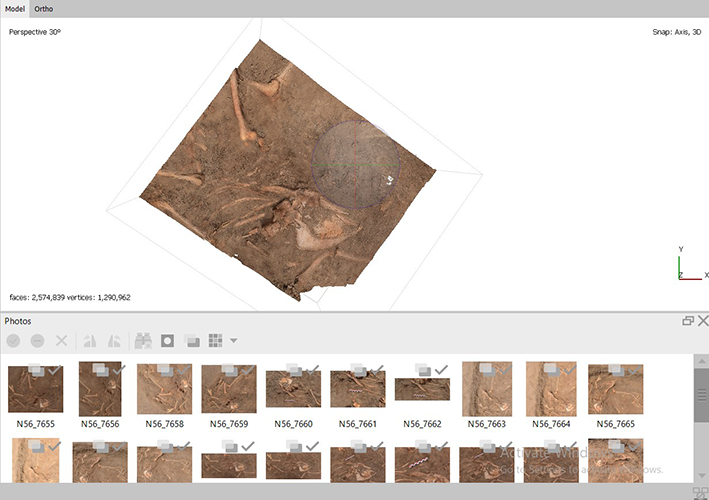

In the middle of the area in question, a shallow depression with an irregular outline was found. First thought to be an unfinished burial pit, it might in fact be a marog-digging pit. Its dimensions are 1.97 meters in length, 1.67 meters in width, and 0.23 meters in depth.

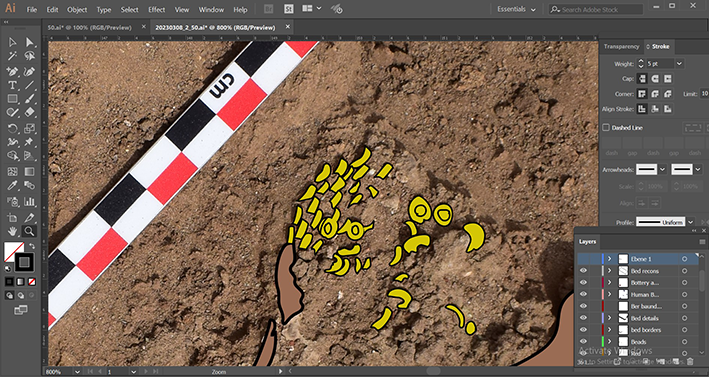

The pit was dug into the alluvial soil and found filled with compacted sand, containing numerous brownish-grey clay clumps, medium to large in size,. Some human remains were found in the northeastern part of the pit − most likely coming from nearby burial pits. Most of the burials in Trench 3 appear to have been looted and dispersed human bones were found across the surface of the trench.

Of course, it is also possible that the pit itself was cut by the ancient looters (maybe in Medieval times) when they were looking for burial pits at the site.

Nevertheless, the gap between the otherwise evenly aligned east-west graves is unlikely to be coincidental. One possible explanation for the gap in burial pits in Trench 3 is that we have cut into an area used for funerary practices and intentionally kept clear of graves. Although, as we have not excavated the entire cemetery, this is still difficult to fully judge.

Interestingly, similar spatial patterns can be observed at Ukma, another provincial Kerma cemetery, where areas void of graves are in particular present in the southern part between Classic Kerma burial pits which are comparable to those at GiE 003 (see Vila 1987, general plan of the site). These recurring patterns suggest that such gaps were common in Kerma cemeteries.

Further analysis, including additional excavations of GiE 003 and comparison with other Kerma cemeteries, might allow us to better understand the reasons for these gaps. A better comprehension of the spatial dynamics of Trench 3 within the context of GiE 003 could provide new insights into patterns of funerary practices during Kerma times.

References:

Budka et al. 2023 = Budka, J., Rose, K., Ward, C., Cultural diversity in the Bronze Age in the Attab to Ferka region: new results based on excavations in 2023, MittSAG 34 (2023), 19–35.

Budka 2024 = Budka, J., Introduction. Regionality of resource management in Bronze Age Sudan: an overview and case studies, in: J. Budka and R. Lemos (eds), Landscape and resource management in Bronze Age Nubia: Archaeological perspectives on the exploration of natural resources and the circulation of 751 commodities in the Middle Nile; Wiesbaden 2024, 19–33.

Vile 1987 = Vila, A. (avec les contributions de Guillemette Andreu et de Wilhem van Zeist), Le cimetière kermaïque d’Ukma Ouest, Paris 1987.