Walking through Munich in these warm and sunny days, one could think that nothing happened, that there is no worldwide pandemic. As an archaeologist working in Egypt and Sudan, this illusion seems completely unreal to me. I am still checking the covid-19 data from the two countries in the Lower and Middle Nile on a daily basis and news from friends and colleagues arrive via twitter, whatsapp and email. Since a few weeks, there are unfortunately also corona cases in the region of Abri, thus close to our MUAFS concession, and the situation in Luxor, Egypt, is far from being under control. Especially in view of the current travel warnings to Sudan and Egypt, I have cancelled the planned season in Luxor for the Ankh-Hor project. And we still have no idea when we can go back to the Attab to Ferka region – very thought-provoking times indeed and my thoughts are first of all with all Egyptians and Sudanese who are now facing major challenges which go far beyond health issues.

Well – with the Luxor field season cancelled and the Sudan field season on hold, my team is currently working on different tasks and we are especially focused on the analysis of our past seasons and on preparing publications. We still are working partly in home office and our monthly jour fixe meetings for the ERC DiverseNile project are run digitally via zoom.

With the summer term of LMU coming towards an end and the summer break approaching, I thought it would be beneficial for our team spirit to meet again in person – of course wearing masks and keeping the appropriate distance.

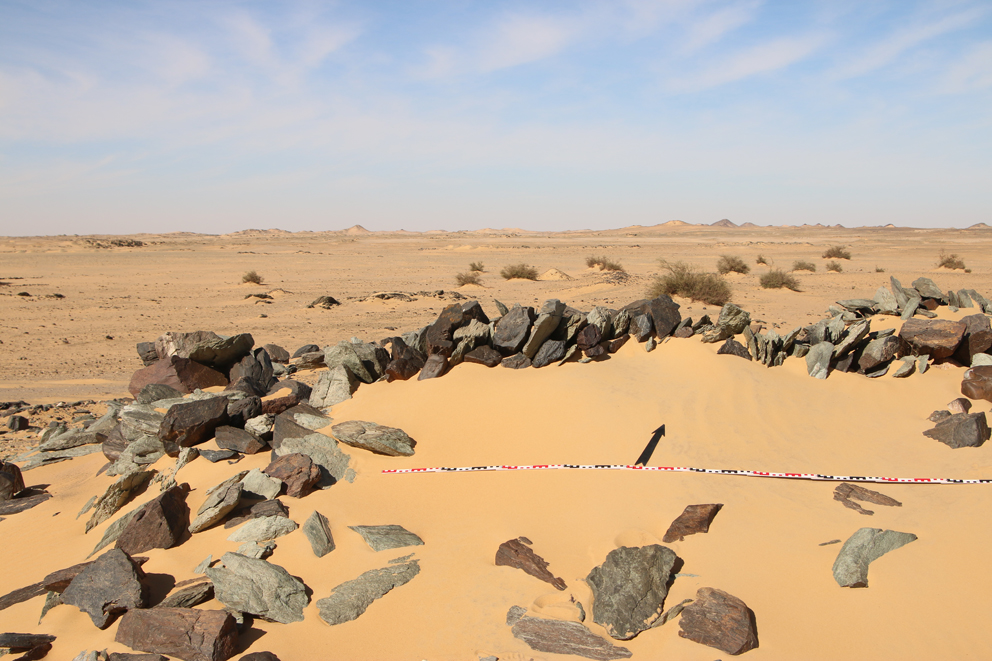

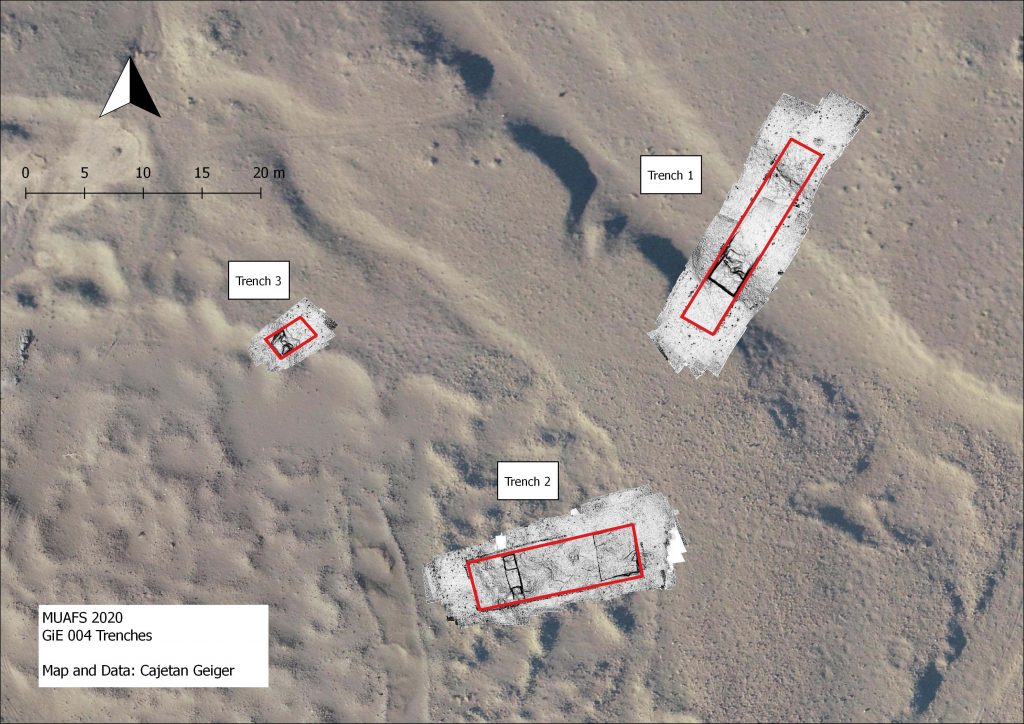

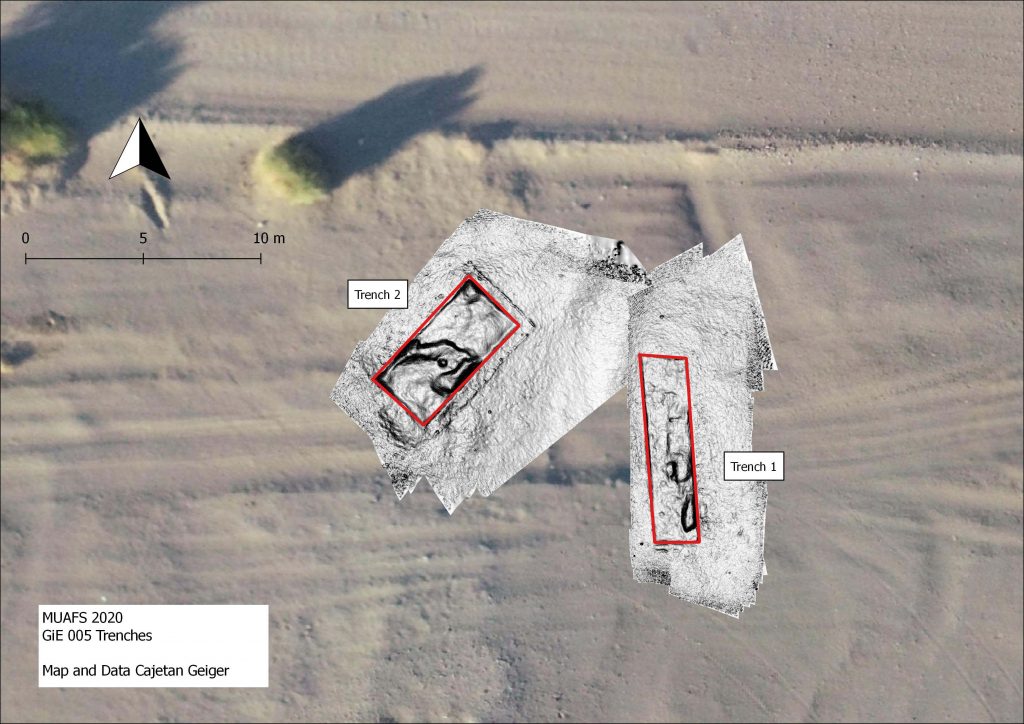

This weekend, we therefore had a very stimulating meeting focusing on digital archaeology. This is nothing brand-new for us – my former ERC AcrossBorder project used many computer-based tools such as spatial analysis, 3D modelling, image analysis etc. Our workflow in the field included a digital documentation system which was already introduced to the MUAFS project in 2020. It is based on a geodetical survey by a total station instrument and image-based 3D modelling via “Structure from Motion” (SfM). Because of the utilization of standard equipment already present on excavations (total station, digital camera and regular mobile computers) the system is robust and flexible. We employed it for three main tasks of various scales and contexts at Sai: 1) excavations in single-context surfaces, 2) excavations in subterranean rock-cut chambers, 3) kite aerial photography for establishing a digital landscape model of the area of interest.

Although we are very happy with our digital documentation system (of which we owe a lot to Martin Fera from Vienna), some work steps could be improved and especially Cajetan invested already much time in thinking about alternations and new solutions to improve the workflow. With our new project, we want to go a bit further, for example by using field-suitable mobile devices. And this is something where we now, due to covid-19, have much time to plan before the next field season.

During our team meeting this weekend, we discussed and tried several new tools and settings, especially our new pen tablets and displays. Patrizia has already great skills working with these tablets, first of all for the digitalization of drawings. But there are so many other possible applications! Patrizia showed us several apps and useful software and we already had some great ideas to incorporate these new tools into the workflow for our projects in both Egypt and Sudan.

DiverseNile is clearly on a new level using computer-based tools compared to AcrossBorders – timely of course, and also of much benefit not just for research, but also for teaching. The upcoming winter term at LMU will be again a digital term – with e-learning and online tools for safety reasons. We are quite well prepared, also for teaching our introduction to archaeological fieldwork via zoom and with mobile devices like tablets and smart phones – we will thus bring the latest developments in digital archaeology to our students.

Much in archaeology does, however, not only depend on the equipment but especially on the skills of the team – we will therefore continue with team building activities in these challenging times in order to be best prepared for the upcoming successful digs in Egypt and Sudan. All fingers and toes crossed that these digs will be possible soon!