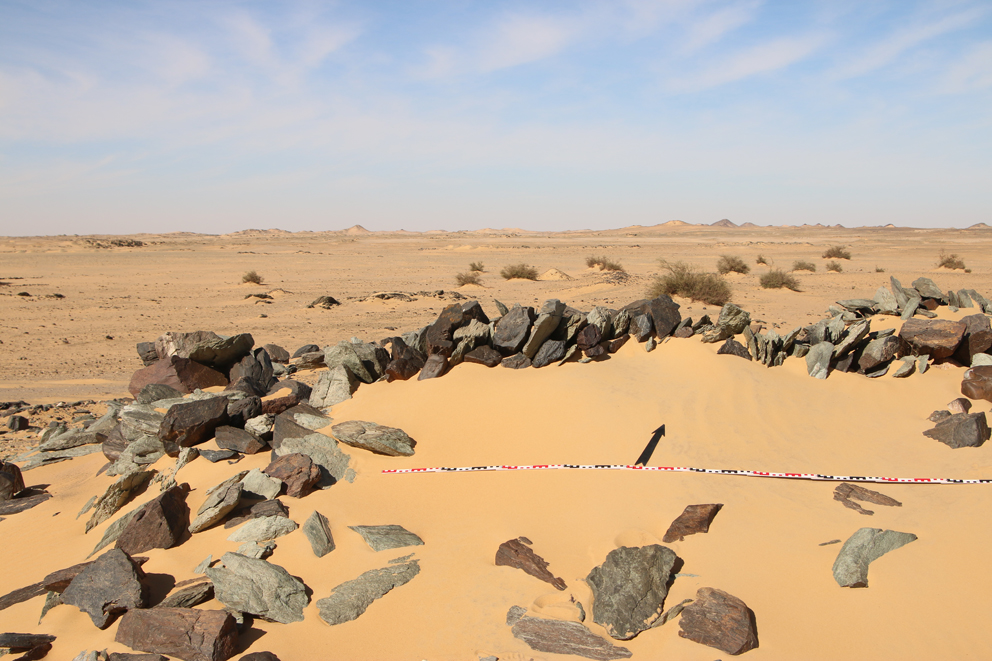

My ERC project DiverseNile focuses on the Attab to Ferka region as a peripheral zone in the neighbourhood of Amara West and Sai Island. However, I do not apply the problematic core-periphery concept for our case study of the Bronze Age, but I have introduced the contact space biography approach.

This morning, I just read a very inspiring paper I found in a new open access journal: Federica Sulas and Innocent Pikirayi wrote about “From Centre-Periphery Models to Textured Urban Landscapes: Comparative Perspectives from Sub-Saharan Africa”.

They review the relations between ancient capital centres in Africa and their peripheries, using Aksum and Great Zimbabwe as case studies. They include a very good introduction about the history of research from central-place theory and world-system theory to network theories and stress that „archaeological research on centre–periphery relations has largely focused on the structure of integrated, regional economic systems“ (Sulas and Pikirayi 2020, 67). Like DiverseNile, they advocate to take the dynamics of interactions into account, the fluidity of what is considered “centre” and what “periphery”.

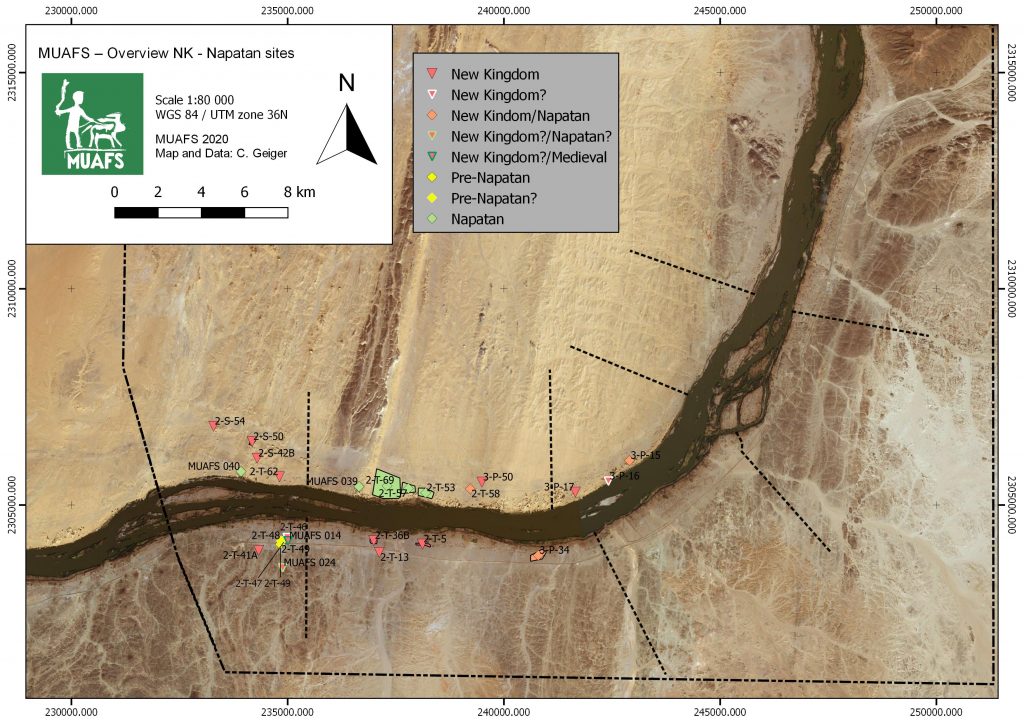

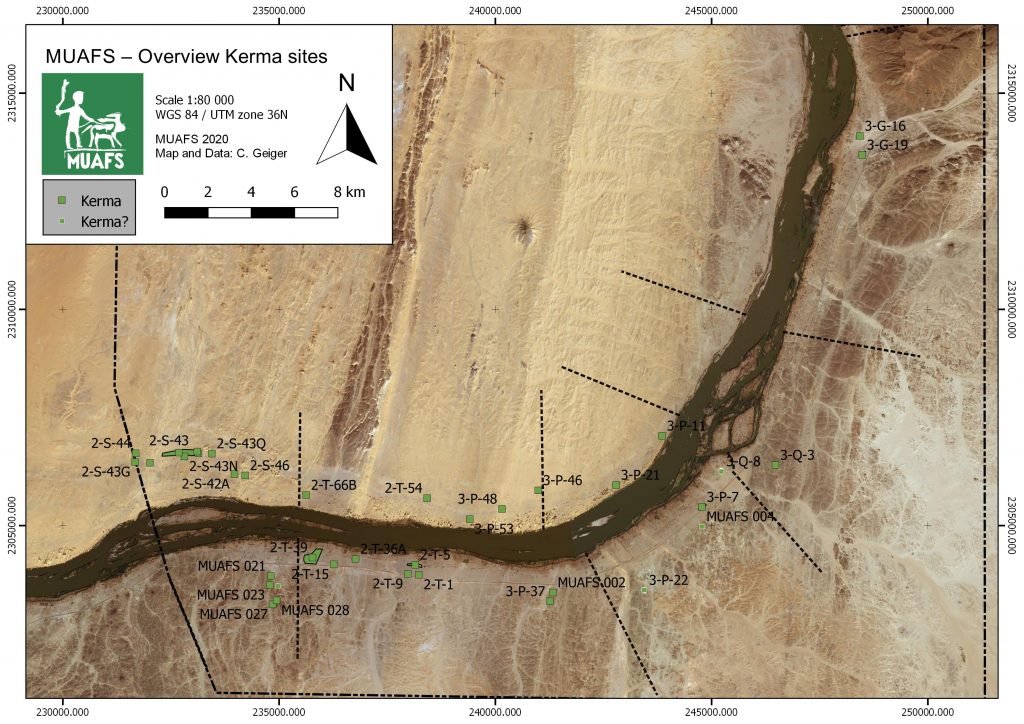

In Nubian studies and Egyptology, there is a considerable gap of work at sites in the periphery of major settlements (see Moeller 2016, 25). At present, despite of much progress on settlement patterns in Nubia during the New Kingdom (see e.g. Budka and Auenmüller 2018) we still know almost nothing about the surroundings of administrative centres set up by the Egyptians in the Middle Nile and the cultural processes within this periphery. The urban centres of this period in the Middle Nile are the Egyptian type towns Amara West, Sai, Soleb, Sesebi and Tombos and Kerma City as capital of the Nubian Kerma Kingdom. Very little rural settlements have been investigated up to now, creating a dearth of means to contextualise the central sites (Spencer et al. 2017: 42). Sites classified as ‘Egyptian’ apart from the main centres are almost unknown (Edwards 2012) and there are only two case studies for Kerma ‘provincial’ sites with Gism el-Arba (Gratien et al. 2003; 2008) and H25 near Kawa (Ross 2014).

If we want to understand the proper dynamics of Bronze Age Middle Nile, this bias between studies of urban centres and rural places in the so-called peripheries needs to be addressed. However, such a new study should avoid the problematic issues of a hierarchy of sites associated with the centre-periphery relations. Thus, DiverseNile intends to offer a new model focusing on the landscape and consequently human and non-human actors in a defined contact space.

Our new approach: beyond core and periphery

Within the DiverseNile project, we understand the Attab to Ferka area as a dynamic, fluid contact space shaped by diverse human and non-human actors. My main thesis is that we need to investigate cultural relations and coalitions between people on a regional level within the so-called periphery of the main urban centres in order to catch a more direct cultural footprint than what the elite sources and state built foundations can reveal. I expect that cultural refigurations reflected in material remains are partly less, partly more visible than in the centres shaped by elite authorities, where dynamic cultural developments are often disguised under an ‘official’ appearance. However, I completely agree with Sulas and Pikirayi that: “Peripheral settlements are always an integral part of the core, as these play a crucial part in enhancing the dynamics exhibited at the centre” (Sulas and Pikirayi 2020, 80). Thus, our new work in the Attab to Ferka region will allow us to contextualise the findings at sites like Amara West and Sai further.

There is still much work to do and data to assess, but I am positive that in the next few years, we will be able to propose a new understanding of ‘centres’ and ‘peripheries’ in Bronze Age Middle Nile (see already the stimulating article by Henriette Hafsaas-Tsakos 2009).

References

Budka, Julia and Auenmüller, Johannes 2018. Eds. From Microcosm to Macrocosm. Individual households and cities in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Leiden.

Edwards, David N. 2012. The Third-Second Millennia BC. Kerma and New Kingdom Settlements, 59–87, in: A. Osman and D.N. Edwards (eds.), Archaeology of a Nubian frontier. Survey on the Nile Third Cataract, Sudan. Leicester.

Gratien, Brigitte et al. 2003. Gism el-Arba, habitat 2. Rapport préliminaire sur un centre de stockage Kerma au bord du Nil, Cahiers de Recherches de l’Institut de Papyrologie et d’Égyptologie de Lille 23, 29–43.

Gratien, Brigitte et al. 2008. Gism el-Arba – Habitat 2, Campagne 2005–2006, Kush 19 (2003–2008), 21–35.

Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette 2009. The Kingdom of Kush: An African Centre on the Periphery of the Bronze Age World System, Norwegian Archaeological Review 42, 50–70.

Moeller, Nadine 2016. The Archaeology of Urbanism in Ancient Egypt. From the Prehistoric Period to the End of the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge.

Ross, T.I. 2014. El-Eided Mohamadein (H25): A Kerma, New Kingdom and Napatan settlement on the Alfreda Nile, Sudan & Nubia 18, 58‒68.

Spencer, Neal et al. 2017. Introduction: History and historiography of a colonial entanglement, and the shaping of new archaeologies for Nubia in the New Kingdom, 1‒61, in: N. Spencer, A. Stevens and M. Binder (eds.), Nubia in the New Kingdom. Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions. British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 3. Leuven.

Sulas, Federica and Pikirayi, Innocent 2020. From Centre-Periphery Models to Textured Urban Landscapes: Comparative Perspectives from Sub-Saharan Africa, Journal of Urban Archaeology 1, 67–83 https://www.brepolsonline.net/doi/epdf/10.1484/J.JUA.5.120910