Time flies by, especially when you are enjoying and/or are very busy! This clearly holds true for our last days here – they were extremely demanding but also very pleasant and full of important results and discoveries.

We managed to close the excavation in Kerma cemetery GiE 003. The original aims for the 2023 season there, building on our work from 2022, were to clarify its dating, the distribution of certain burial pit types and to check for aspects of cultural diversity. All of this worked out perfectly and more details will follow soon. For now, the most important result is the discovery of a Pan-Grave style burial in Trench 5, located just north of Trench 2 from 2022 (with Kerma Moyen burials). Since some of our pottery from 2022 was already indicating that we might have the presence of what is normally called Pan-Grave horizon, this did not come as a big surprise, but simply as what I was really wishing for.

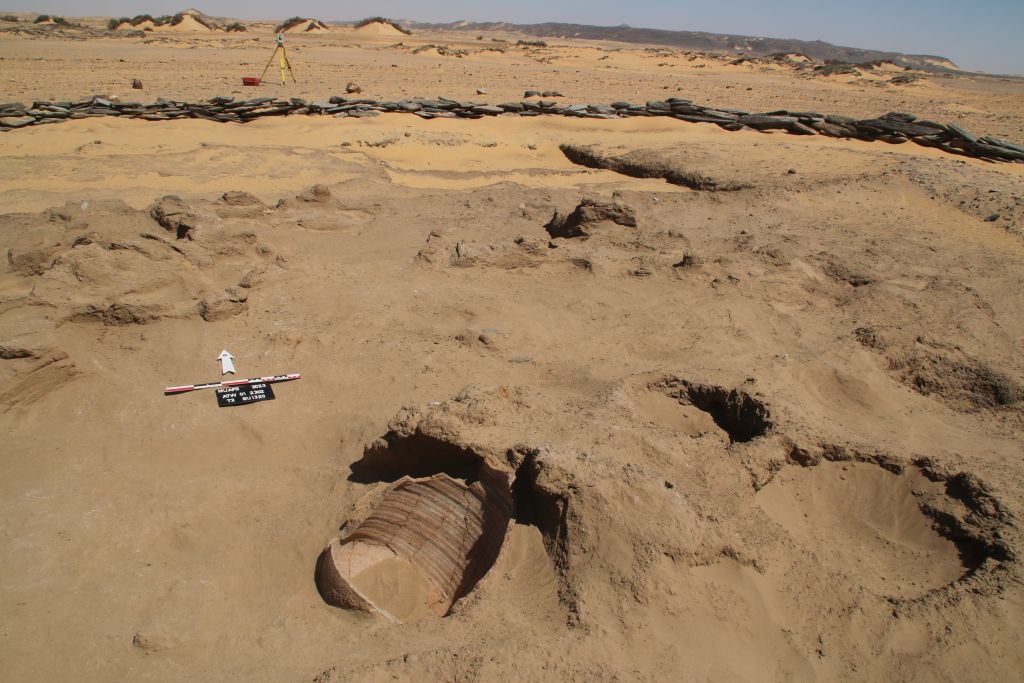

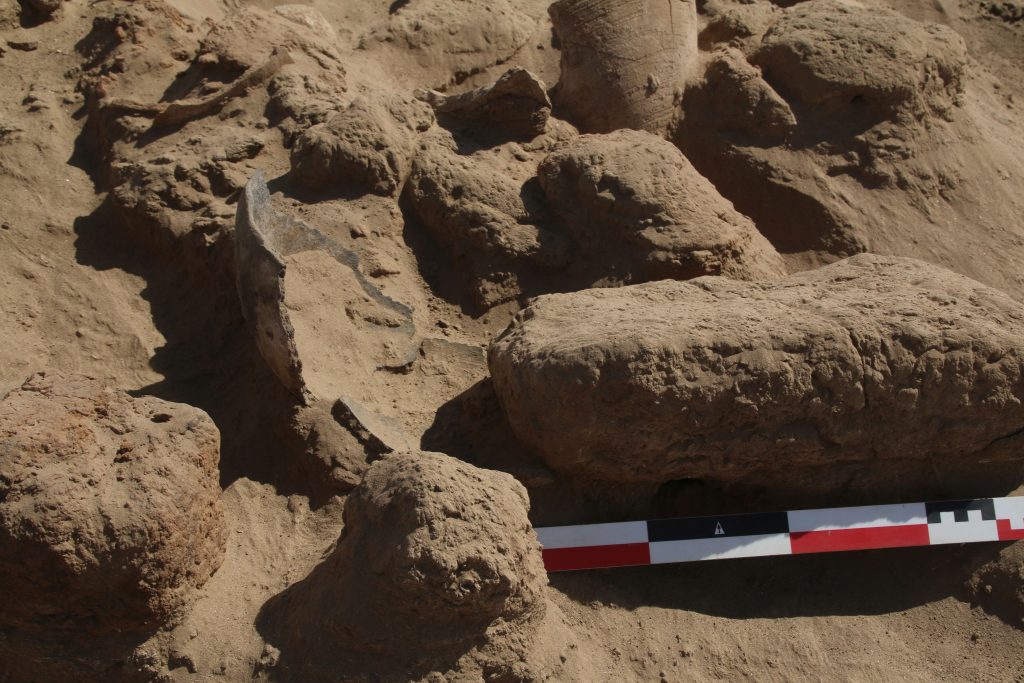

Feature 50, the Pan-Grave burial pit, yielded not only the remains of a funerary bed, of goat offerings as well as jewelry and ivory objects but also several intact pots. This complete beaker with some repair holes is a typical Black Topped ware associated with the Pan-Grave horizon.

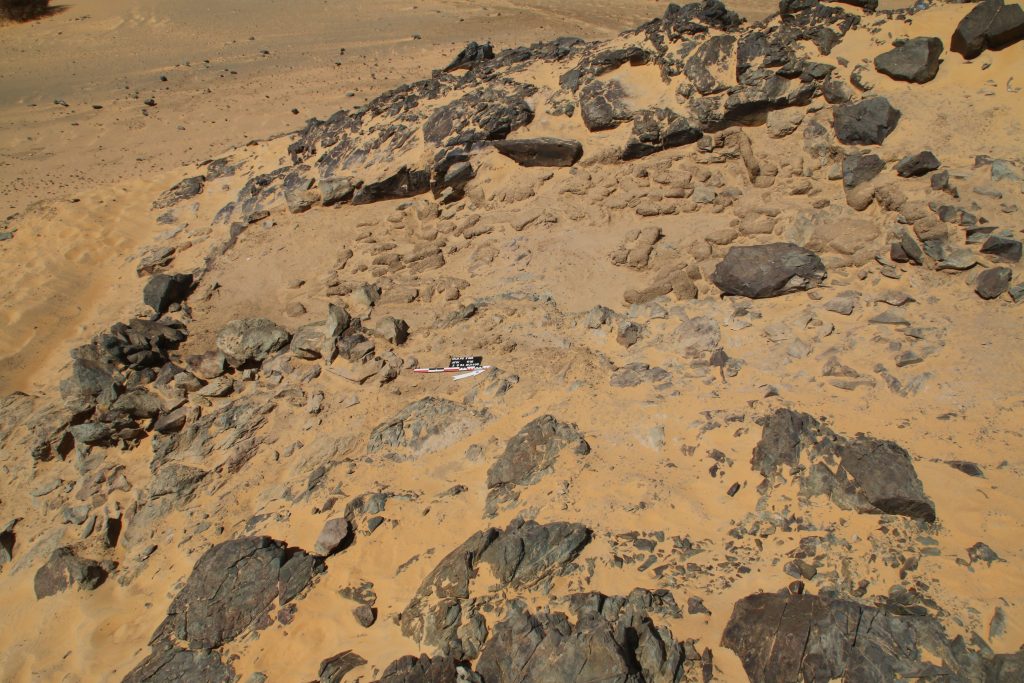

In Trench 4, there were two important niche tombs cutting Classic Kerma burial pits. At least Feature 66 (which was discovered just before closing for the weekend last week) is clearly associated with Classic Kerma material culture as well – thus providing much food for thought about who decided when (and why) to be buried in a niche tomb rather than in the more common rectangular burial pits? The burial of Individual 18 found in Feature 66 was unfortunately looted, but it can be reconstructed as a contracted burial which was placed in the oval niche without a funerary bed with the head in the West and the feet in the East.

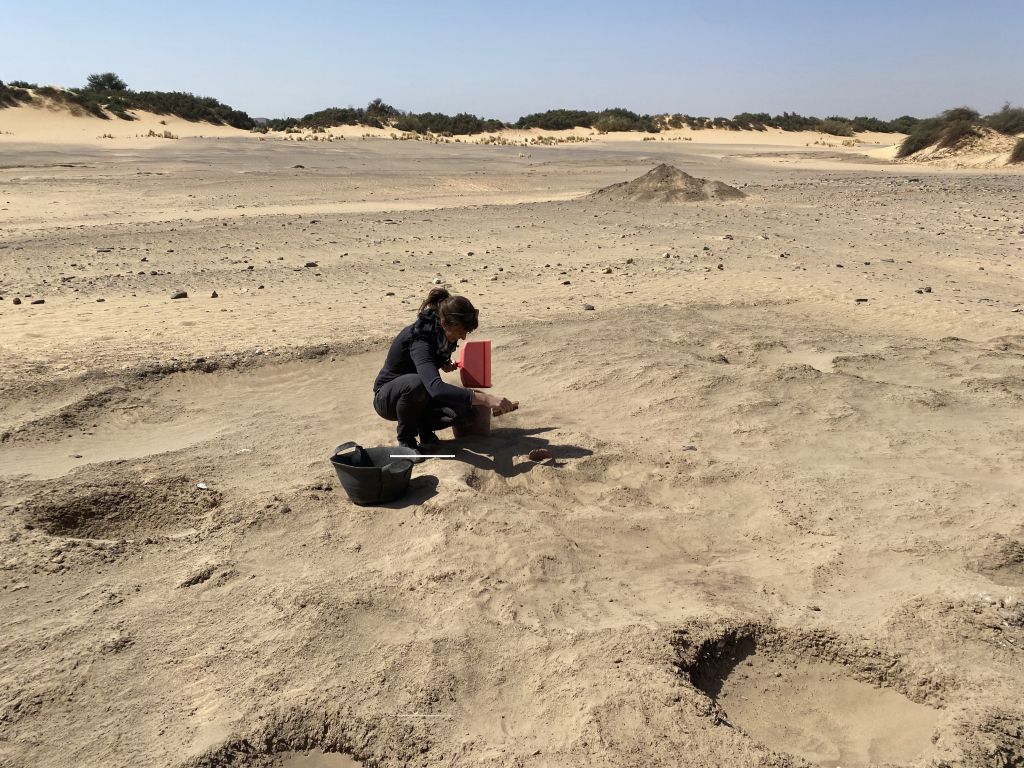

Furthermore, we finished sampling of pottery from AtW 001, GiE 003 and the Vila site 2-S-54. Giulia did prepare more than 100 samples which we will hopefully analyze together with Johannes Sterba of the Atominstitut Wien by iNAA, just like the samples we took already in 2022. Our focus was on a range of Nubian wares and Egyptian-style Nile clay wares.

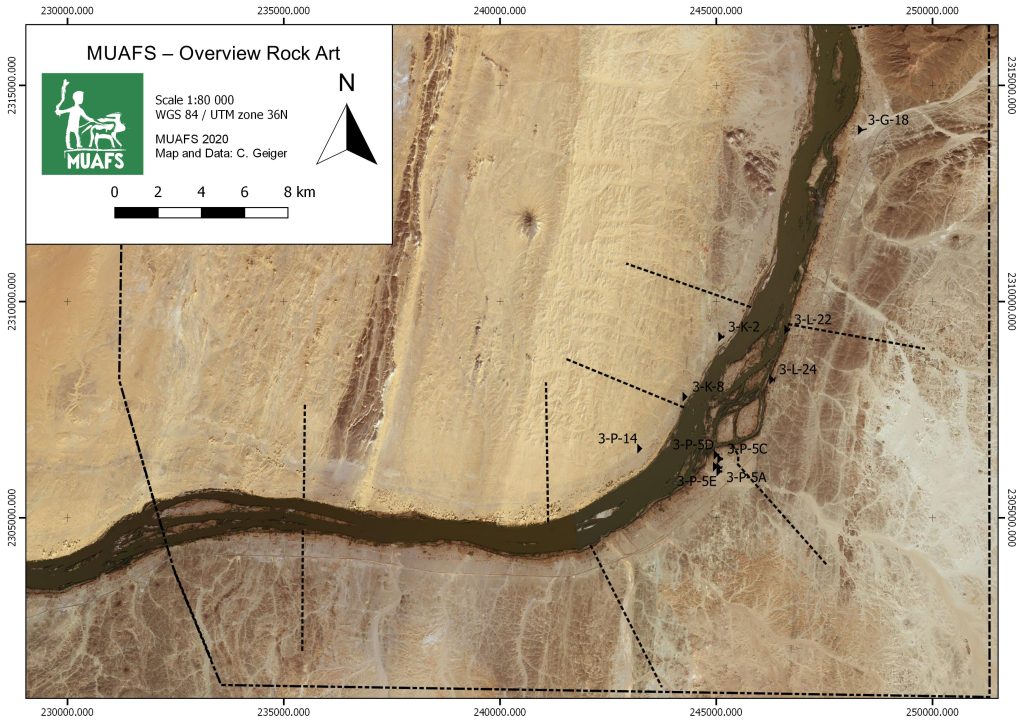

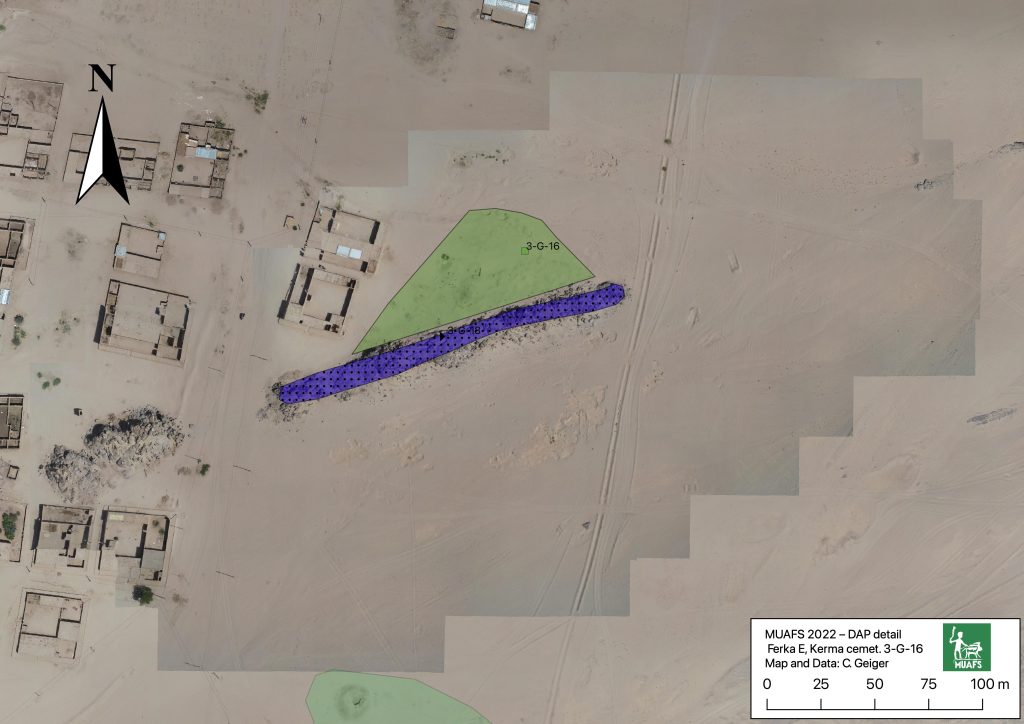

Thanks to the support of NCAM and our colleague Sami, Kate managed to conduct at least three days of Drone Aerial Photography after the crash of our own Phantom 4 Pro. I also managed to squeeze in some surveying on the west bank – with the discovery of some amazing new 18th Dynasty sites – very promising for the next season!

By now, most of our team members have already left – many thanks to all of them! It was a particular pleasure to welcome Mohamed and Tasabeh from Al-Neelain University – hope to see you again next year!

The remaining small team of Jose, Sofia, Huda and I will be busy finalizing everything here in Ginis before our own departure early next week. More updates about our results of the 2023 season will follow soon insha’allah.