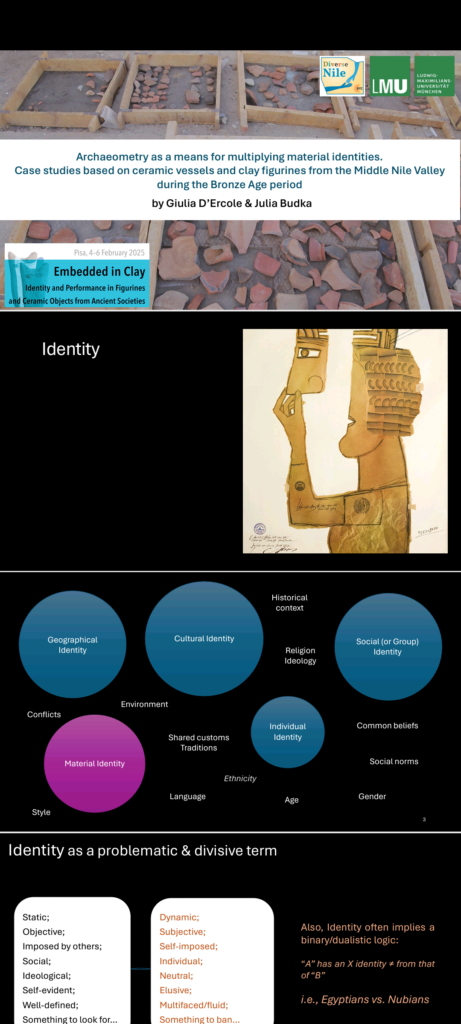

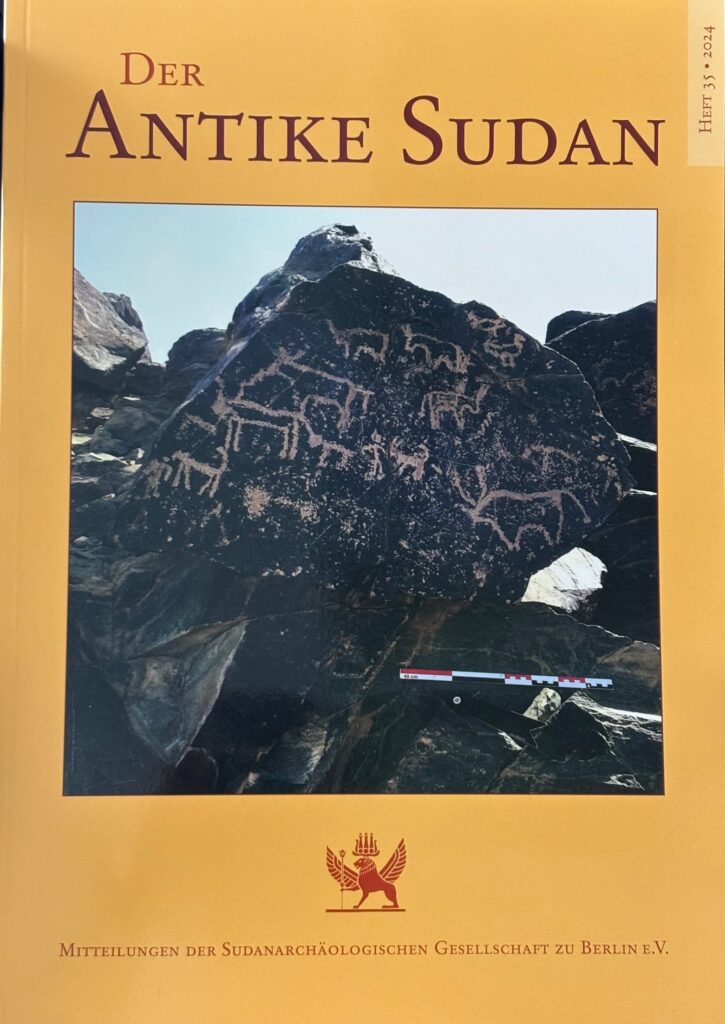

As rock art in Sudan continues to be one of my favourite research topics, I am very pleased that a new article of mine on the rock engravings of Kerma in the MUAFS concession has just been published and that one of the beautiful boulders with cattle depictions has also made it onto the front page of MittSAG 35!

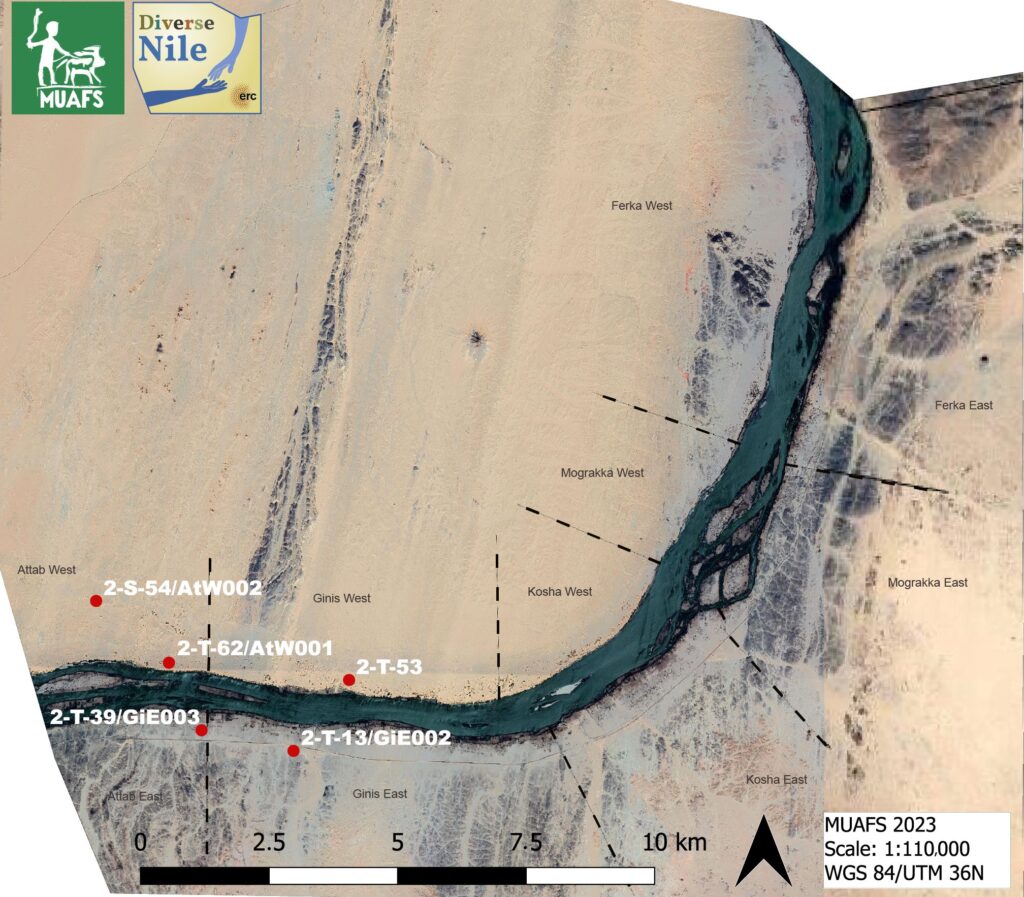

In the paper “Cattle motifs in Nubian rock art of the Bronze Age – a preliminary update from Kosha, Mograkka and Ferka” (Budka 2024), my aim was to show the potential of the little-known rock art from the MUAFS concession, especially for the Kerma period. During this period, cattle motifs are particularly prevalent in rock art in Sudan.

Among other sites, I highlighted some aspects of the largest rock art cluster within the MUAFS concession, 3-P-5, located on the border between Mograkka and Kosha. This remarkable site comprises more than 400 individual rock carvings.

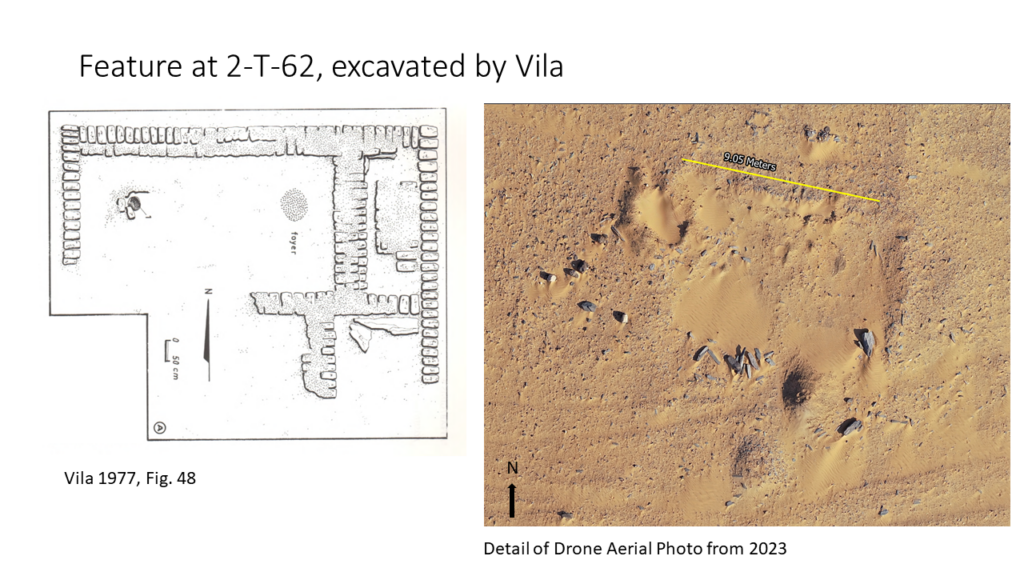

The rock art boulder which made it to the cover of the MittSAG is a prominent rock which shows human-animal interaction and is likely to be interpreted as a ‘pastoral scene’ (see Polkowski 2021). It was already documented by Vila in the 1970s (Vila 1976, 86, fig. 37.3). In various lines, with different styles and shapes of horns, not only cattle, but also birds (probably geese) as well as a goat, a possible calf (or another goat?) and a dog are depicted. Such scenes find plenty of parallels, especially in the Third and Fourth Cataract regions, for which I give the details in the article. It is reasonable to assume that this panel depicts the daily life of pastoralists. All in all, the important role that livestock, particularly cattle, played for people in the Kosha region – during the Bronze Age, but also later – is very clear at site 3-P-5.

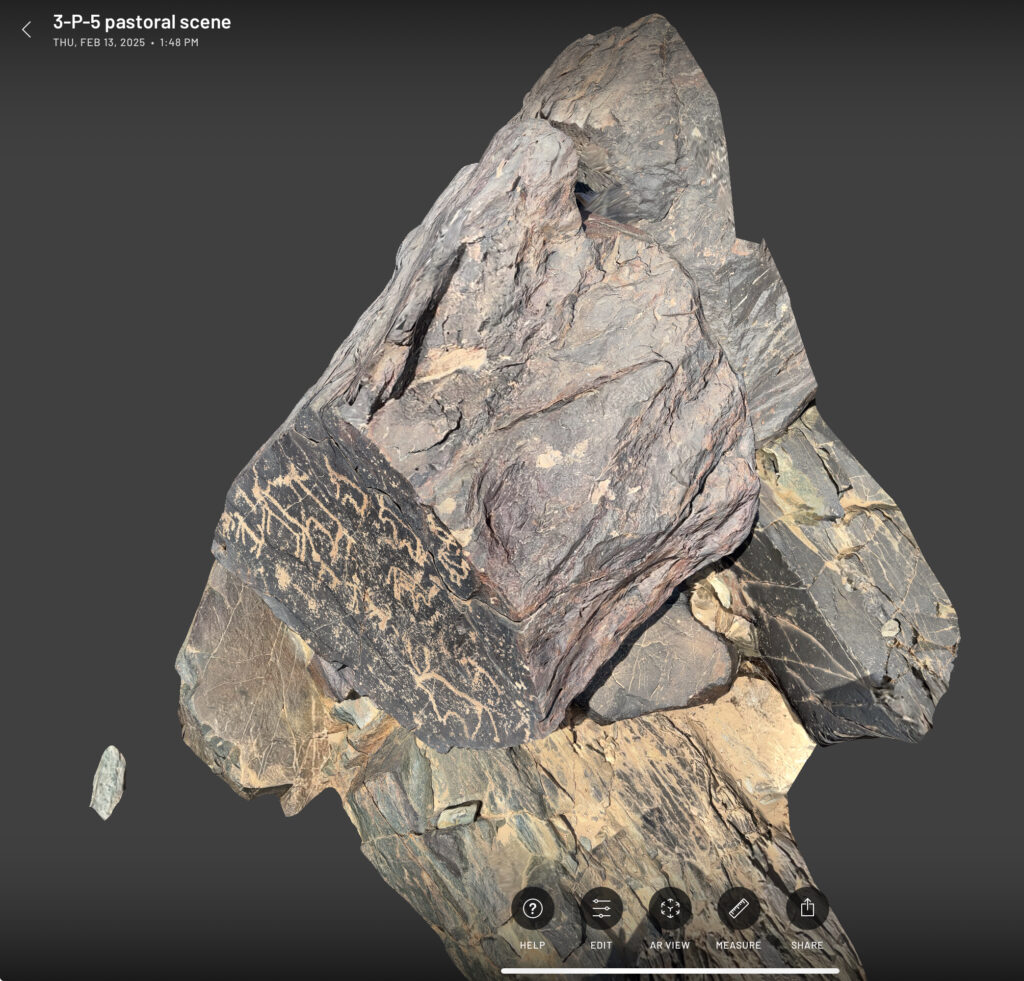

In February 2025, I was very fortunate to be back in the Attab-Ferka region and had the chance to revisit the intriguing site 3-P-5. The aim was to test new ways of documentation of the rock art – introducing 3D scanning with the ultrafast, highly accurate mobile app Scaniverse – a tool, we have been using in Egypt and for our ceramics here in Munich in the past two years. 3D modelling in rock art research in general has made great progress worldwide in recent years – from standard image-based techniques to more sophisticated methods such as terrestrial 3D laser scanners. Given the situation in Sudan, where war is still raging, my focus was on testing the quality of an ultra-fast scanning technique.

The results of documenting rock art with Scaniverse were simply amazing – the app makes it possible to capture not only details, but above all the complete shape and position of the boulders. Larger areas were quickly captured with the iPad, smaller boulders and details are well suited to the smaller iPhones.

Here is a screenshot of the 3D scan of the panel that was first published by Vila in the 1970s, relocated by us in 2020, re-photographed and published in 2024, also becoming a cover star (see above), and now 3D scanned in 2025. The high-resolution scan allows extreme zooming in for details and you can measure every tiny detail.

This example shows very nicely the progress in the documentation of rock art in recent years and makes me very positive about the possibilities of tackling new relevant questions on this fascinating research topic in the near future.

References

Budka, J. 2024. Cattle motifs in Nubian rock art of the Bronze Age– a preliminary update from Kosha, Mograkka and Ferka, MittSAG – Der Antike Sudan 35, 9‒19.

Polkowski, P. L. 2021. “Cattle in the Nile Fourth Cataract rock art: the site of El-Gamamiya 67 as an example.” In Bayuda and its neighbours, ed. by A. Obłuski, H. Paner and M. Masojć, 71-91. Turnhout: Brepols.

Vila, A. 1976. La prospection archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise). Fascicule 4: District de Mograkka (Est et Ouest), District de Kosha (Est et Ouest). Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.