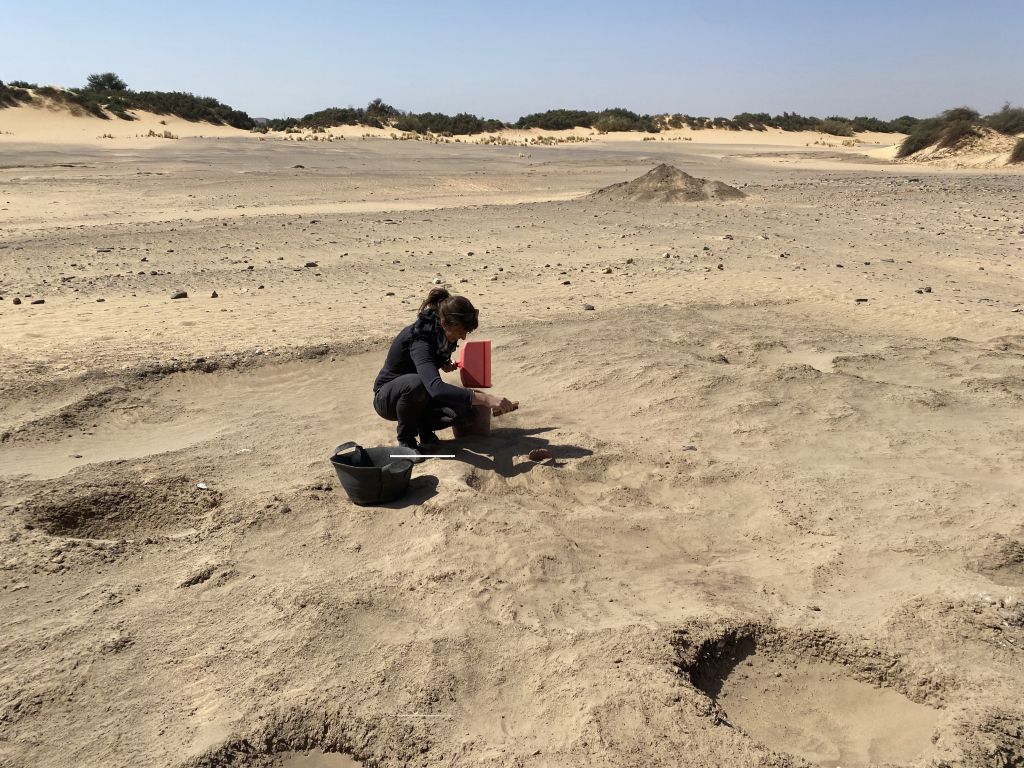

The excavation season of the fourth MUAFS campaign lasted from January 23 to March 18 2023, and focused on aims of the ERC Project DiverseNile, investigating Bronze Age sites (Kerma and New Kingdom) and cultural diversity in the region. The team was supported by Huda Magzoub Elbashir as Antiquities Inspector from NCAM. Our major activities in the 2023 season are summarised in the following.

Excavations

We focused on Bronze Age sites in the area of Ginis and Attab. Our selection included two settlement sites, AtW 001 and site 2-S-54, and one cemetery, GiE 003. Work was carried out with the support of a team of 12 local workmen from Ernietta, Ginis and Attab.

AtW 001

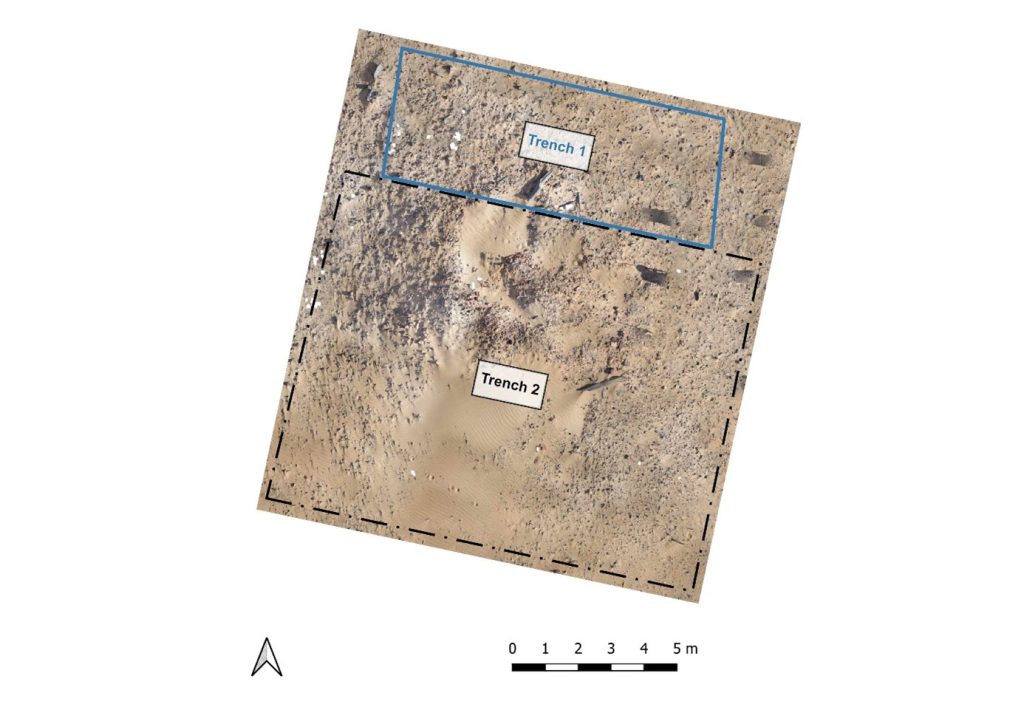

In 2023, the complete mound of this site in Attab West was excavated (Trench 2). Substantial layers of mud brick collapse were found as well as several phases of poorly preserved mud brick structures.

The domestic character of the site is also obvious from many ashy spots, rubbish deposits including much animal bones and charcoal as well as loads of broken pottery and a surprisingly large number of intact and almost intact vessels. In addition, several round and oval-shaped storage pits were documented, some of them with traces of firing/ash and possibly also connected with heating/cooking.

Most importantly, the same ashy layer on the alluvial surface like in 2022 was reached in the northern part of Trench 2. It is now clear that apart from a slight natural slope, most of the mound-like appearance of site AtW 001 was composed of settlement debris and especially mud brick debris in several layers, all dating to the 18th Dynasty.

Vila site 2-S-54

Structure 1 at site 2-S-54 is a domestic building measuring 6.5 x 3.5m on the interior and preserved to more than 80cm in height, datable to the 18th Dynasty. We cleaned it from windblown sand and exposed a substantial layer of mud brick debris as well as internal mud brick structures. The feature seems to have been divided in at least three parts, presumably with an open courtyard in the centre. It is still unclear where the main entrance of the structure was originally located (one side entrance seems to have been on the east side in the centre, leading into the open courtyard). Ceramics and collapsed mud bricks were also found on the slope towards the south and this area still needs to be fully cleaned and documented.

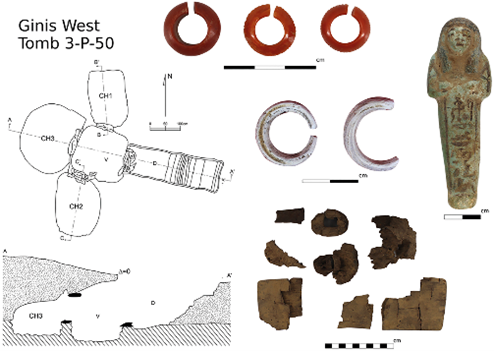

GiE 003

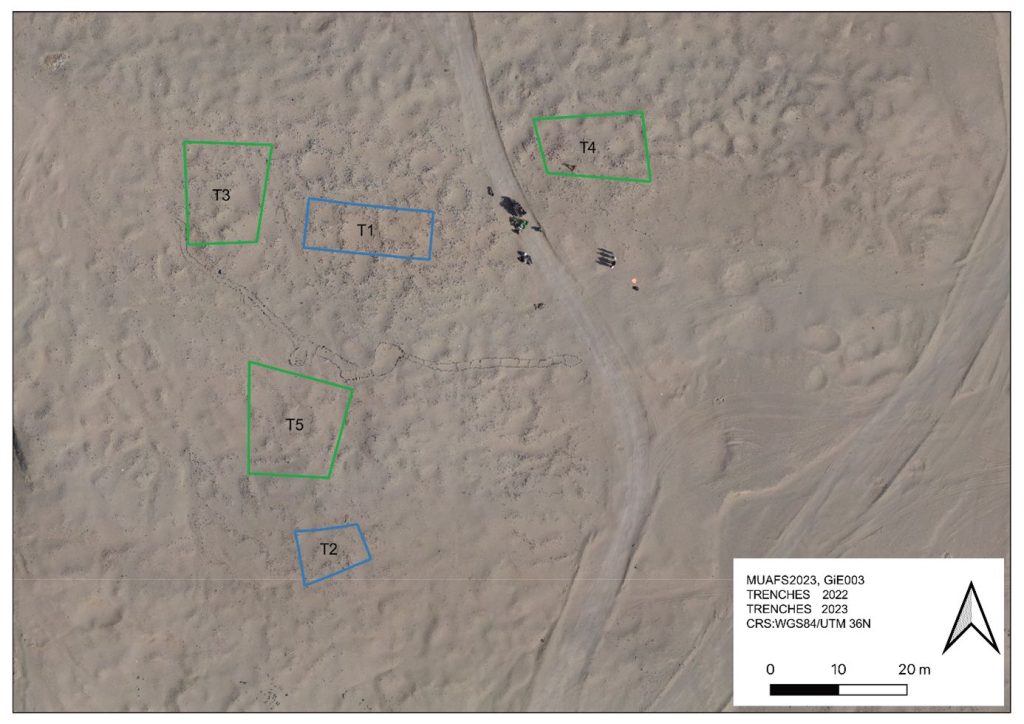

We excavated three new trenches (Trenches 3, 4 and 5) to check the extension of this Kerma cemetery, the distribution of burial types and chronological aspects.

The oldest material was exposed in Trench 5, just north of the Middle Kerma burials in Trench 2. One Middle Kerma circular pit (Feature 53) and a total of four pits associated with Pan-grave style material were discovered.

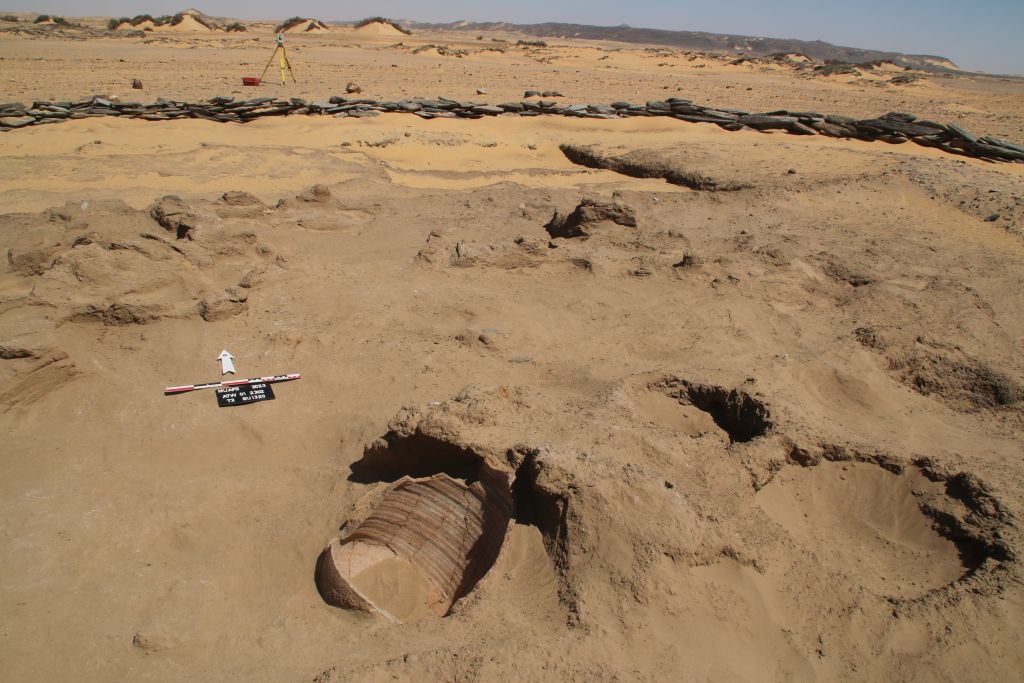

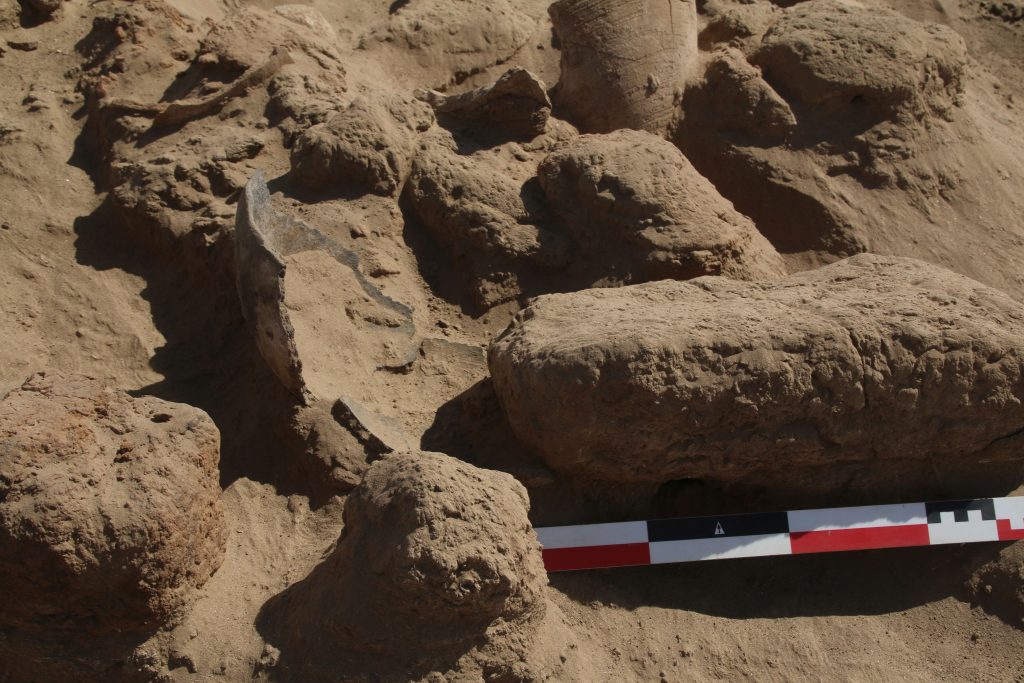

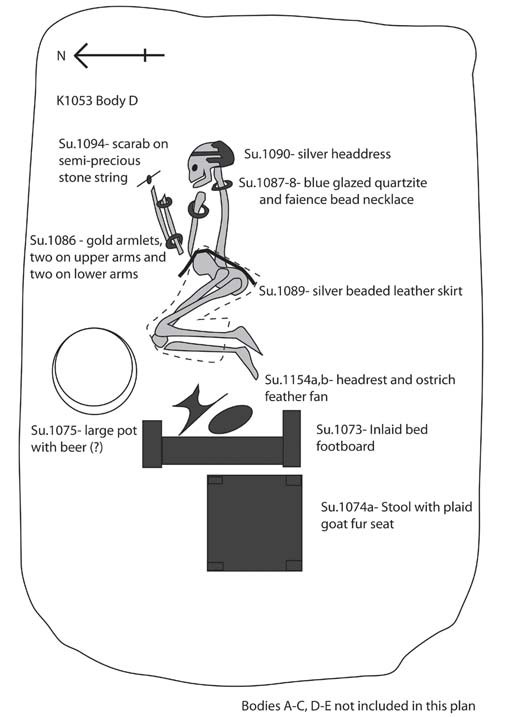

The largest pit, Feature 50, contained the remains of a wooden bed frame, the remains of a human contracted burial, several goat offerings and a considerable number of intact pottery vessels, comprising Black-topped fine wares as well as incised and impressed decorated vessels.

Trench 3 yielded a total of 14, Trench 4 ten new Classic Kerma burial pits, closely resembling our results from 2022 in Trench 1. These burials are rectangular east-west oriented burial pits with rounded corners, vertical walls, and two depressions in the east and west for the funerary bed of which wooden remains were found in some of the features. Two niche burials in Trench 4 also seem to date to the Classic Kerma time.

Drone Aerial Photography

Kate Rose was busy conducting Drone aerial photography (DAP) at the excavated sites and on a larger scale at Attab West, Attab East, Ginis East and Ferka East. Many precise measurements were taken with our new Trimble Catalyst GNSS Antenna and extensive mapping of drystone walls in Attab and Ginis West was carried out as well.

Find documentation

We used a total of 566 find bag numbers in the 2023 spring season. 229 finds were registered, photographed and recorded in detail in the Filemaker Database.

Simultaneously to the excavations, I carried out the recording of the pottery. The numerous settlement material from AtW 001, accounting to more than 10.000 sherds, was very time consuming to process, especially since a large number of pottery vessels could be reconstructed from fragments to complete vessels like an amazing hybrid cooking pot. A total of 43 vessels was documented by drawing in 2023.

The 2023 season survey

Two Vila sites in Attab West and one in Kosha East were newly identified and documented as well as seven new MUAFS site in Attab East, Attab West and Kosha East. A number of these sites is difficult to date and might be sub-recent.

In sum, our 2023 season was very successful, achieving all planned work tasks despite of the looting events and the destruction of site 2-S-54. Especially cemetery GiE 003 with its mixed material culture of Middle Kerma, Pan-Grave and Classic Kerma illustrates cultural encounters between various Nubian groups in the region. The living aspect of these cultural encounters seems to be traceable at sites like 2-S-54 where both Egyptian and Nubian ceramics were found, rectangular and circular buildings appear side by side and mud bricks were used jointly with dry-stone architecture.

Plenty of post-excavation work is now waiting for us and updates will follow soon.