David Edwards‘ recent publication of ‚Pharaonic‘ remains in the Batn el-Hajar provides an important comparison point for us to understand the evidence from DiverseNile’s concession area from Attab to Ferka. From a mortuary landscape perspective, Edwards criticises archaeology’s traditional focus on elite tombs in the Middle Nile saying that we „should not narrow our perspectives, to the exclusion from our narratives of the vast majority of the population who were buried otherwise“ in areas other than the centres of foreign colonial power in Nubia (Edwards 2020: 396).

Until recently, a similar picture could be drawn for Egypt. Despite large non-elite cemeteries being known since the early 20th century (e.g., Matmar or Gurob), a monumental/elite bias characterised historical narratives about New Kingdom Egypt (see Richards 2005). Only recently, with the identification and excavation of large non-elite cemeteries at Amarna (Kemp et al. 2013), more scholars are paying attention to other social realities beyond the imposition of elite social spaces.

The long history of archaeology in the Middle Nile has been strongly marked by colonisation, ancient and modern. Nubia’s history, especially in the New Kingdom, has remained, for a long time, in the shadow of Egypt’s history. This manifested as the discipline’s Egyptocentric focus on sites of colonial administration, its textual sources and elite cemeteries, which yielded Egyptian-style objects interpreted as essentially ‚Egyptian’—a manifestation of the alleged acculturation of passive local communities placed in lower ranks of ‚civilisation‘. Traditional, Egyptocentric research agendas contributed further to silencing past colonised groups, which only appear in Egyptian textual sources in inferior positions.

As a result, we still know barely anything about the majority of the population of New Kingdom Nubia, which inhabited areas other than the major colonial centres of power, e.g., Aniba, Sai, Soleb. The cemeteries at these sites house a small number of monumental tombs that, although used collectively, still represent a tiny fraction of society across the history of ancient colonial Nubia.

Who were the majority of the population of New Kingdom Nubia? Where did those people live and where were they buried? Where did they come from? Under what conditions did they live (and die)? Although research is moving forward to address new topics (see Spencer et al. 2017), these are questions that haven’t been explored for Nubia yet, mostly due to archaeology’s focus on acculturation/Egyptianisation in the New Kingdom.

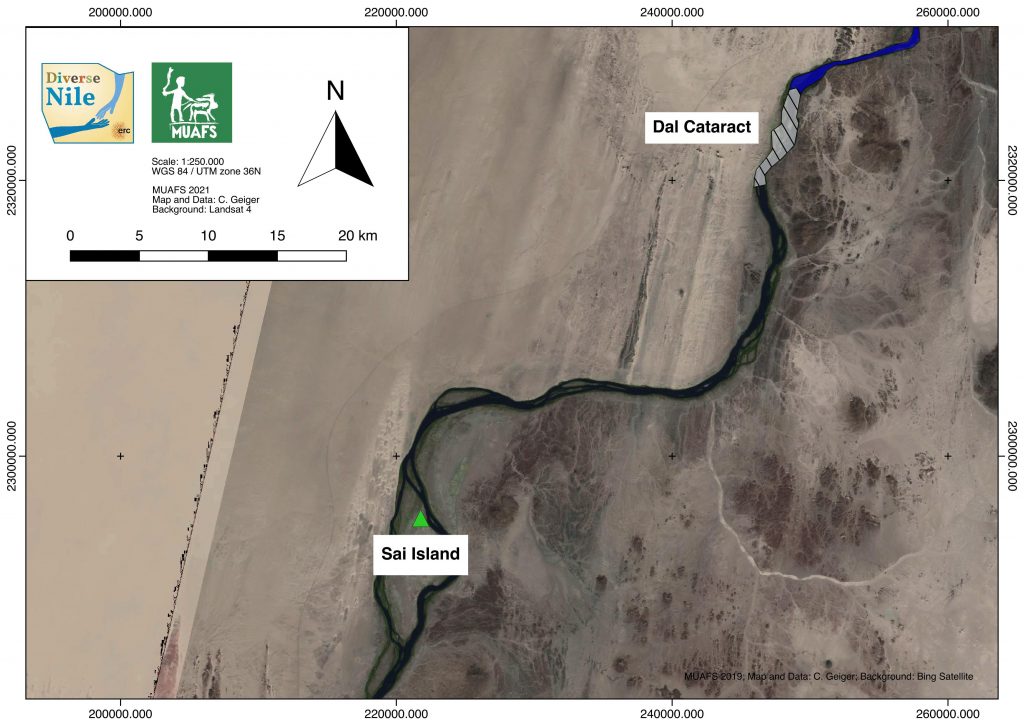

Areas such as the Batn el-Hajar and the region south of Dal cataract, including DiverseNile’s concession from Attab to Ferka, are unlikely to yield monumental elite tombs. However, peripheral, today inhospitable desert areas along the Middle Nile hold an enormous potential to impact our narratives about ancient Nubia’s colonial past, shedding light on alternative histories, experiences and forms of being-in-the-world beyond Egyptological/Egyptocentric research interests grounded on sites of Egyptian colonial administration in the New Kingdom. So, where did the majority of the population live and die in New Kingdom Nubia? Likely in the geographical and social gaps along the Nile still to be fully explored.

Even at colonial administrative centres, such as Aniba, Sai and Soleb, social relations were more complex than simply being ‚Egyptian‘. Recent work confirmed, through isotopic analysis, that local individuals lived at those sites and worked in colonial administration; e.g., the master of goldsmiths Khnumose and other individuals close to him (Budka 2021). My previous work on the distribution and use of Egyptian-style objects in local contexts in colonial Nubia, which included subversive transformations of stylistic and use patterns, also show that things weren’t homogenous in colonial Nubia (Lemos 2020).

Currently, we know very few non-elite cemeteries in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. If social relations were far from being uniform at colonial centres of power, at non-elite cemeteries there was even more room for negotiations, which resulted in the shaping of alternative material realities and experiences of colonisation. Examples from non-elite cemetery of Fadrus in Lower Nubia allow us to understand better such negotiations, which could result in alternative social relations other than imposed colonial hierarchies (e.g., collective engagement and collaboration), as I have argued in a forthcoming paper (Lemos forthcoming).

Fadrus alone doesn’t fill the gap in our knowledge about the vast majority of the population of New Kingdom colonial Nubia, neither does the collective use of elite tombs at the centres of colonial administration. In both elite, administrative sites and non-elite sites, Egyptian-style material culture opens windows to complexity and diversity beyond previous homogenising interpretations of New Kingdom colonial Nubia that reflect disciplinary colonial traditions and interests. Therefore, turning our attention to ‚peripheral‘ regions previously neglected holds an immense potential for us not only to detect this vast mass of population left out of historical narratives, but also to uncover alternatives to colonial homogenisation (ancient and modern) through people’s diverse experiences of landscape, society and culture.

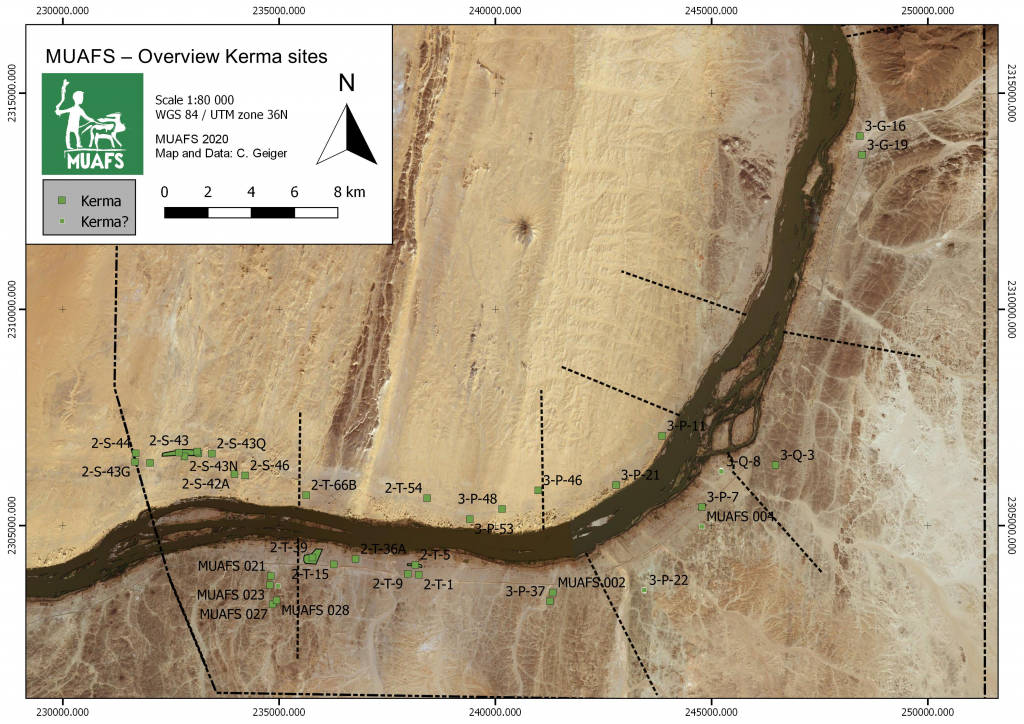

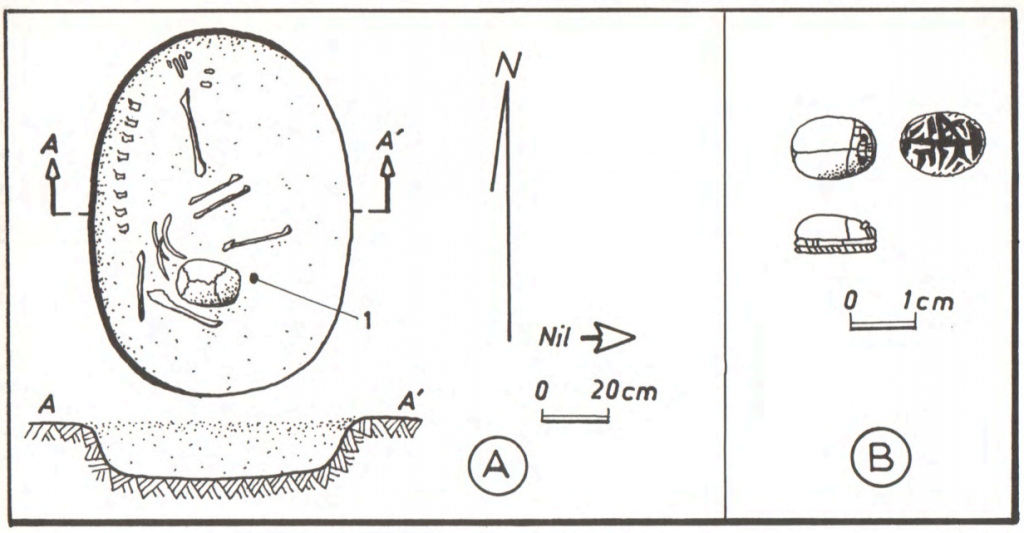

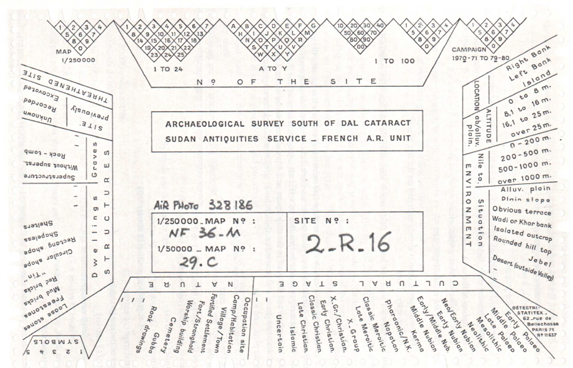

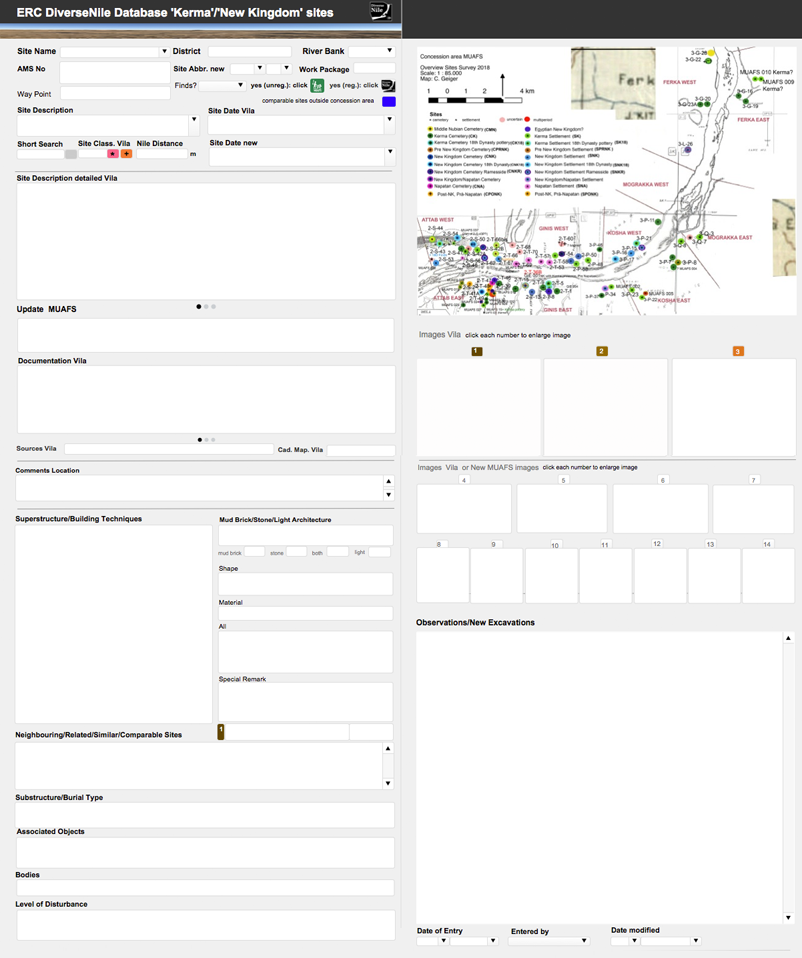

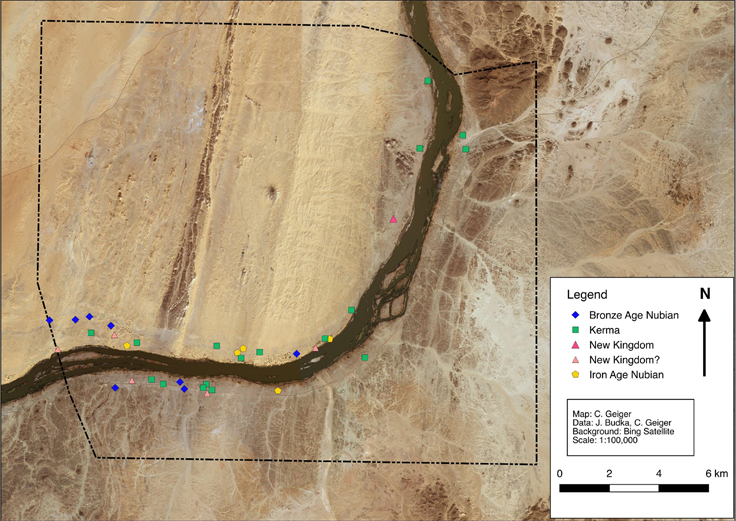

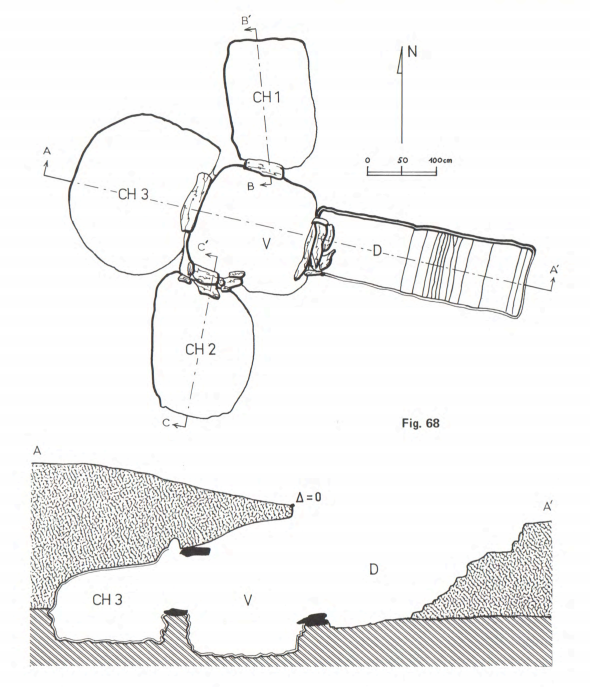

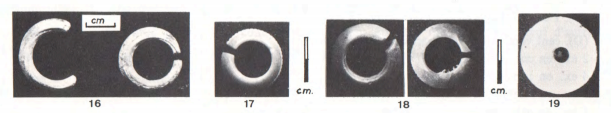

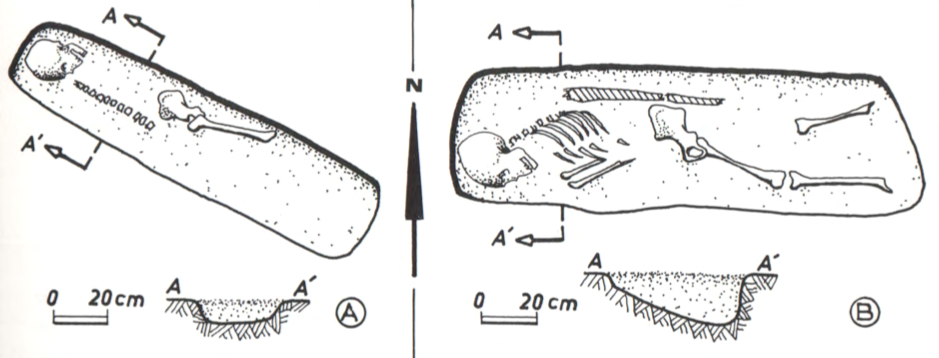

Vila’s survey identified several burial sites, which are comparable to non-elite cemeteries, although most of the Vila sites don’t seem to be large „formal“ cemeteries like Fadrus (figure 1). DiverseNile’s focus on the regions where the majority of the population of the New Kingdom colonial Nubia lived and died is an important step towards understanding diversity and complexity in heterogeneous New Kingdom Nubia. Exploring such sites in comparison with other sites in Nubia holds a huge potential for us to rewrite Nubia’s diverse history in the New Kingdom, which was characterised by various, sometimes competing material experiences of colonisation, especially considering the creative potential of people living and dying at the fringes of society.

References

Budka, J. forthcoming 2021. Tomb 26 on Sai island: A New Kingdom elite tomb and its relevance for Sai and beyond. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Edwards, D. 2020. The Archaeological Survey of Sudanese Nubia, 1963-69. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Kemp, B. J. et al. 2013. Life, Death and Beyond in Akhenaten’s Egypt: Excavating the South Tombs Cemetery at Amarna. Antiquity 87: 64–78.

Lemos, R. 2020. Material culture and colonization in ancient Nubia: Evidence from the New Kingdom cemeteries. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, ed. C. Smith. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1.

Lemos, R. forthcoming 2022. Heart Scarabs and other heart-related objects in New Kingdom Nubia. Sudan & Nubia 25.

Richards, R. 2005. Society and death in ancient Egypt. Cambridge: CUP.

Spencer, N. et al. 2017. Introduction: History and historiography of a colonial entanglement, and the shaping of new archaeologies for Nubia in the New Kingdom. In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived experience, pharaonic control and indigenous traditions, ed. N. Spencer, A. Stevens and M. Binder, 1–61. Leuven: Peeters.

Vila, A. 1977. La prospection archeologique de la valee du Nil au sud de la cataracte de Dal 5. Paris: CNRS.