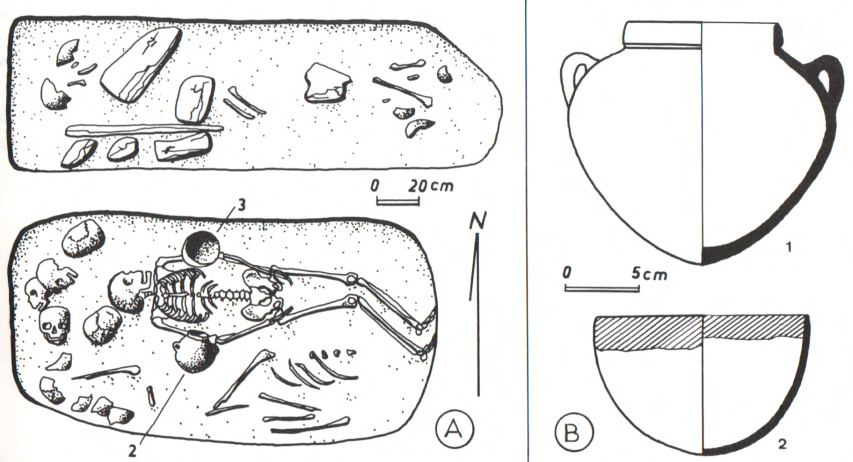

Documentation is the bread and butter of archaeological research. Archaeologists are daily committed to documenting everything: sites formation processes, dwellings, funerary remains, and above all the various products of material culture.

Any method of documentation, from the most essential and traditional (i.e., technical drawing of archaeological strata and finds) to the most elaborated (i.e., image-based 3D-modelling of artefacts, human remains, and sites) constitutes a fundamental step toward archaeological reconstruction. Documentation mainly serves the archaeologist to record and understand the material remains, settlement and funerary features identified during the archaeological excavation and to leave a trace of it. Also, through documentation, a preliminary process of interpretation and critical reading of the data is carried out. Furthermore, the system we adopt to document and classify archaeological data is not unbiased, rather it already implies a methodological choice and a specific scholarly interpretative approach.

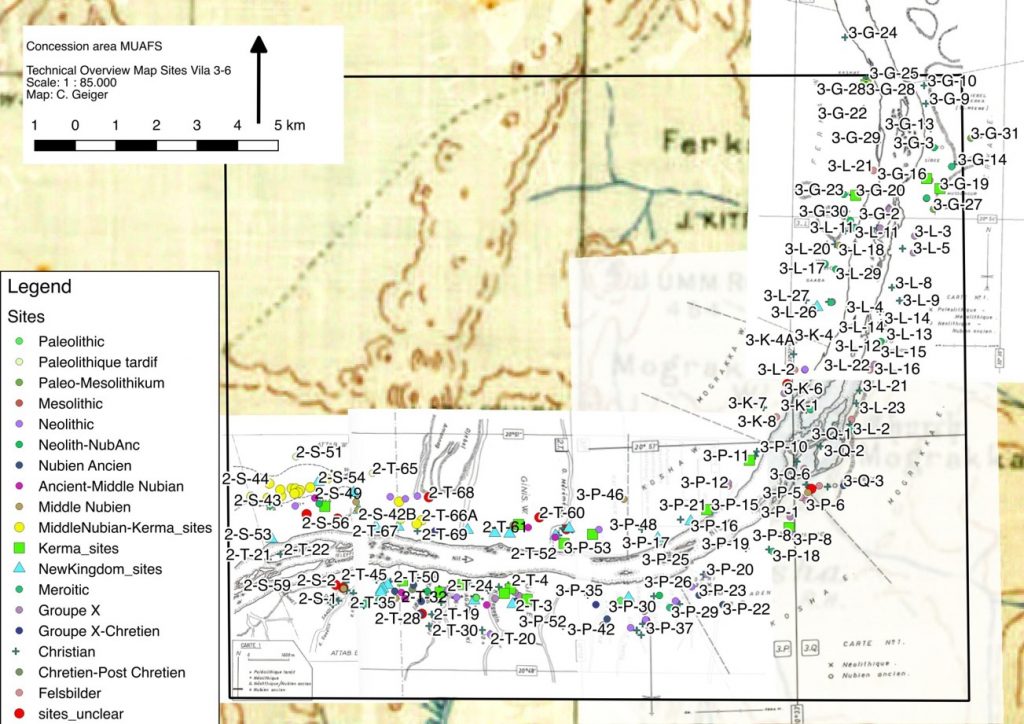

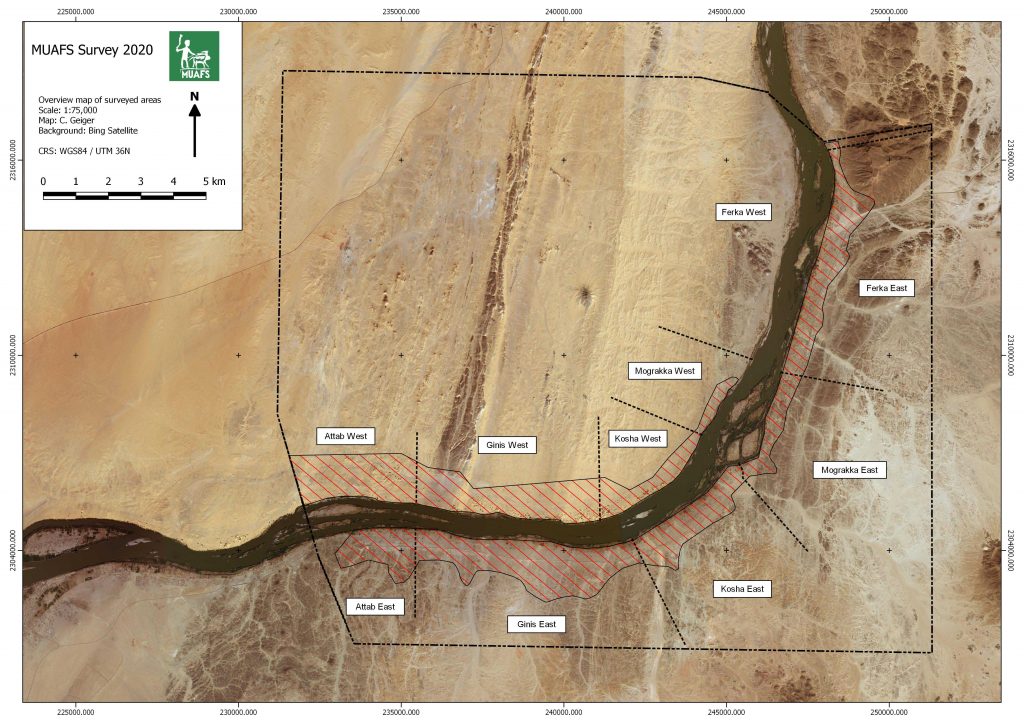

As responsible, within the Work Package 3 of the DiverseNile project, for the technological and compositional analyses of the ceramic materials, I want to outline the method I use for the petrographic classification of the ceramic samples which we are going to analyse from the new concession area in the Attab to Ferka region and from our reference collections (e.g., the AcrossBorders ceramic samples from Sai Island; the New Kingdom/Kerma-Dukki Gel pottery samples; see also D’Ercole and Sterba 2018).

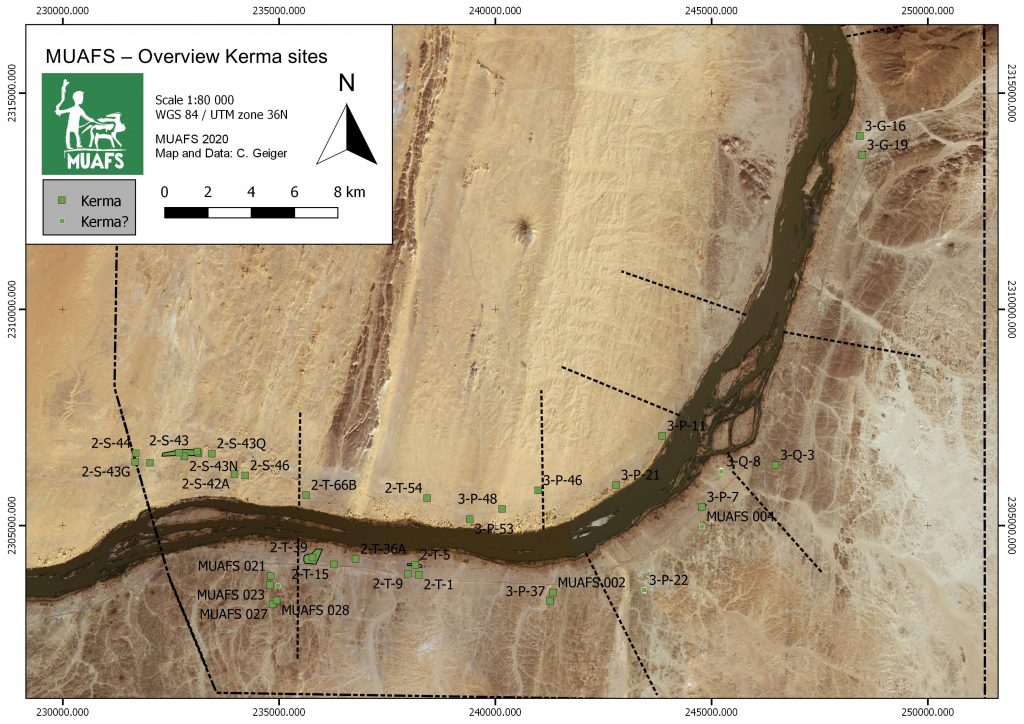

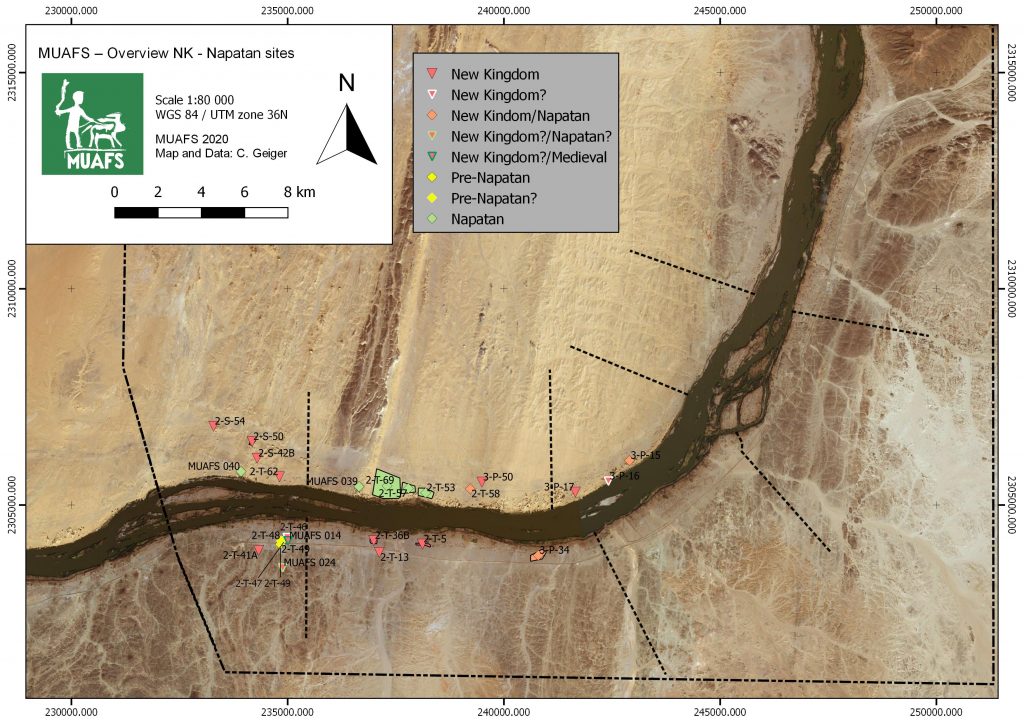

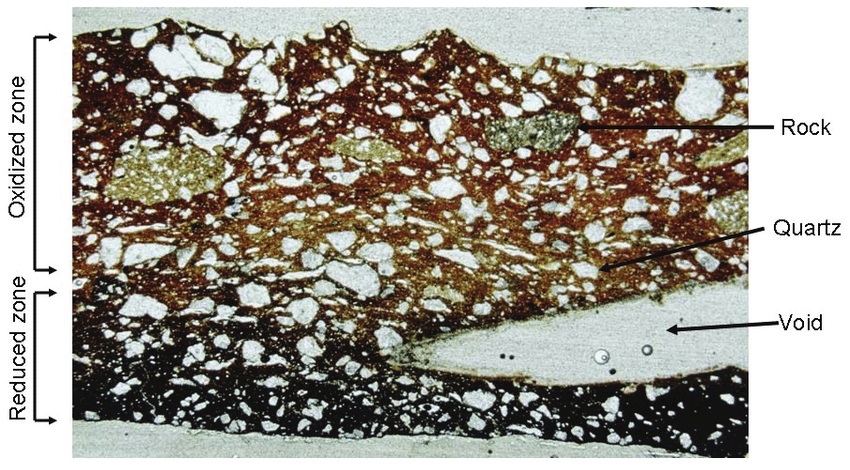

Generally speaking, petrography, via optical microscopy (OM), is a well-established procedure employed to examine ceramic objects and identify the source of clay raw materials and tempers used to manufacture the vessels (Fig. 1). This technique allows answering to crucial archaeological questions on pottery provenance and technology.

In Sudanese archaeology, the interest in provenance and technological studies on pottery started approx. 50 years ago. In 1972, Nordström, referring to the work of Anna Shepard (1956), produced a systematic publication on early Nubian ceramics from the region of Abka-Wadi Halfa and defined the term fabric meaning the set of the compositional and anthropogenic characteristics of the ceramic material that could be determined by microscopic observation and comprised both the composition of the groundmass (or clay matrix) and non-plastic inclusions plus the potter’s technological choices adopted to make the vessel.

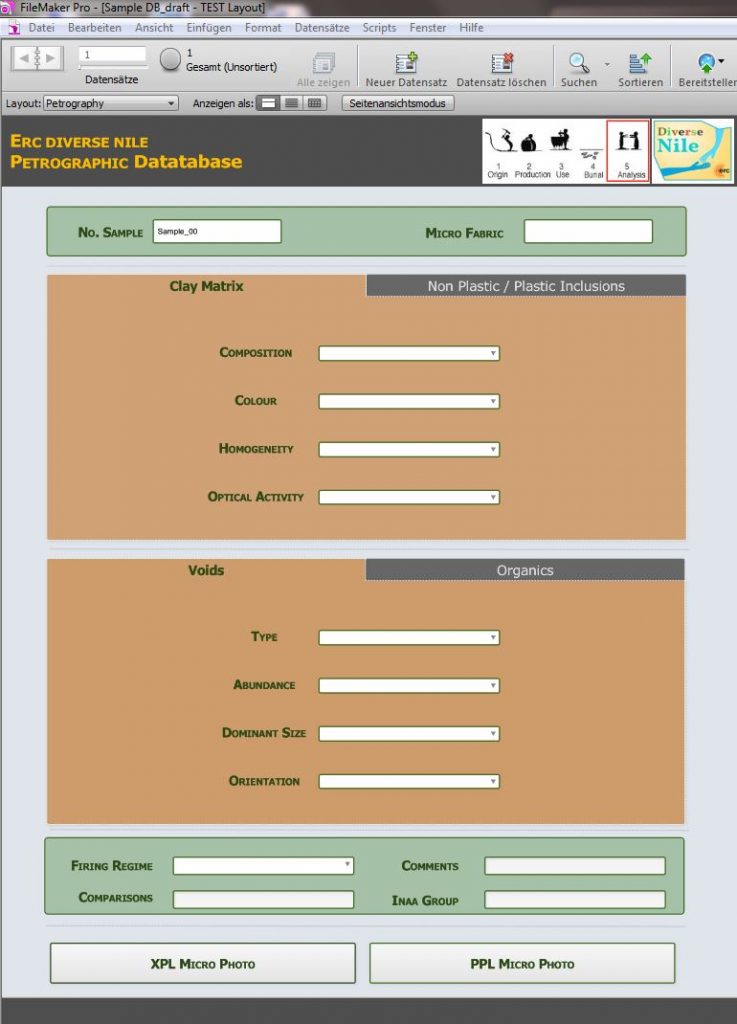

For the study of the ceramic material of our DiverseNile project I have designed a specific petrographic layout within the Filemaker database of the ceramic samples (Fig. 2).

The petrographic layout includes information on the archaeological provenance and dating of the samples. It also correlates the micro fabric or petrographic group to the macroscopic evidence, that is the visual description, shape, function, and macro ware of the ceramic specimens. The consecutive entries inform on a) the groundmass or clay matrix of the sample (i.e., colour, homogeneity and optical activity); b) non-plastic inclusions (i.e., sorting, dominant grain size, maximum grain size, abundance, and mineral composition); c) plastic inclusions (i.e., clay pellets, argillaceous rock fragments etc.); d) porosity (i.e., voids abundance, type, dominant size, iso-orientation); e) organics (i.e., abundance, type, dominant size). The database also notifies on the firing regime of the ceramic sample (i.e., oxidised, reduced, reduced with narrow ox margins, dark core due to insufficient ox, oxidised to reduced). Finally, a graphic field incorporates the microscopic photos of the thin section taken under both cross-polarised (XPL) and plane polarised (PPL) light. Comments, possible comparison with other samples, and a link to the iNAA compositional groups are included as further relevant information.

The purpose of this database is to simplify the data entry of the petrographic evidence and to standardize it according to an easy-to-use, flexible, and consistent classificatory system that embraces the main information on the composition and technology of production of the ceramic data (see among others Quinn 2013).

At a subsequent step, this information will be intertwined with the results obtained from the other laboratory analyses and eventually with the archaeological data to provide a further analytical and interpretive tool for understanding the diversity and complexity of the material culture of the human groups living in the periphery of the Egyptian towns in Sudanese Nubia.

References

D’Ercole, G. and Sterba, J. H. 2018. From macro wares to micro fabrics and INAA compositional groups: the Pottery Corpus of the New Kingdom town on Sai Island (northern Sudan), 171–183, in: J. Budka and J. Auenmüller (eds.), From Microcosm to Macrocosm: Individual households and cities in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Leiden.

Nordström, H. – Å 1972. Neolithic and A-Group sites. Uppsala, Scandinavian University.

Quinn, P. S. 2013. Ceramic Petrography: The Interpretation of Archaeological Pottery & Related Artefacts in Thin Section. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Shepard, A. O. 1956. Ceramics for the Archaeologist. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Smith, M. S. 2008. Petrography, Chapter 6, 73-107, in: J. M. Herbert, T. E. Mc Reynold (eds.), Woodland Pottery Sourcing in the Carolina Sandhills. Research Report No. 29, Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.