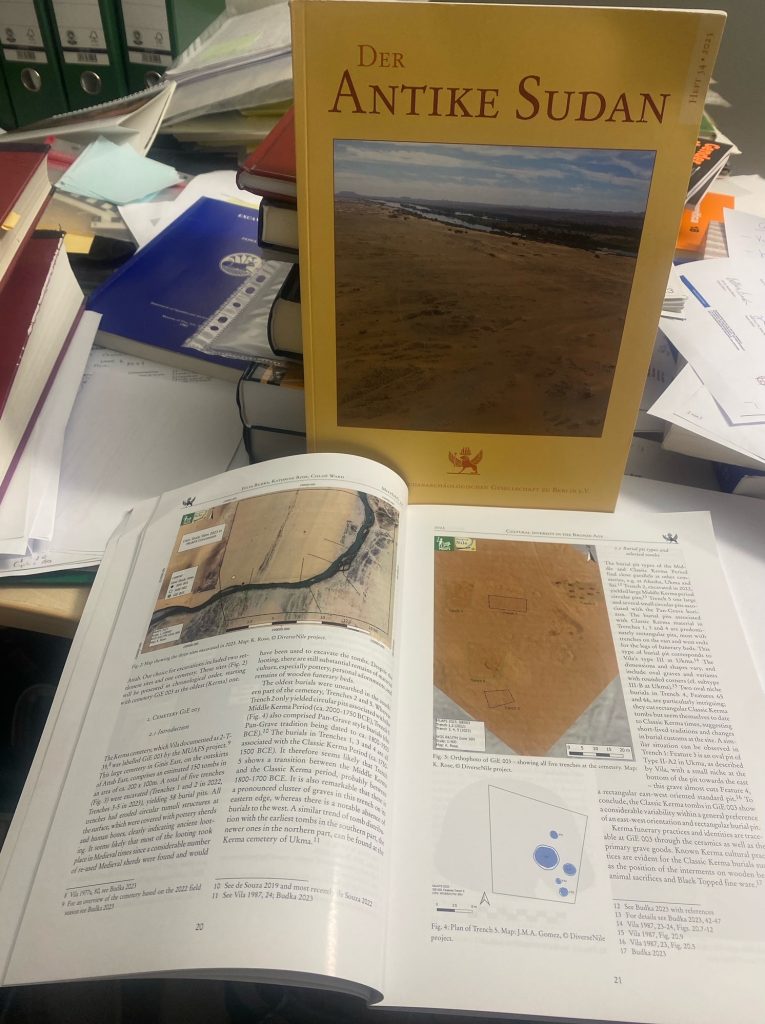

Perfect timing – just before the holidays, the new issue of Der antike Sudan – Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. arrived in our office, hot off the press. It comprises a broad range of topics, including our 2023 excavation report.

Chloë, Kate and I summarised under the title “Cultural diversity in the Bronze Age in the Attab to Ferka region: new results based on excavations in 2023” the most important working steps and results of our field season in Attab and Ginis earlier this year. This work would not have been possible without our Sudanese workmen and the support of all authorities. We are in particular very grateful to Huda Magzoub Elbashir, our NCAM inspector and long-time collaborator and friend.

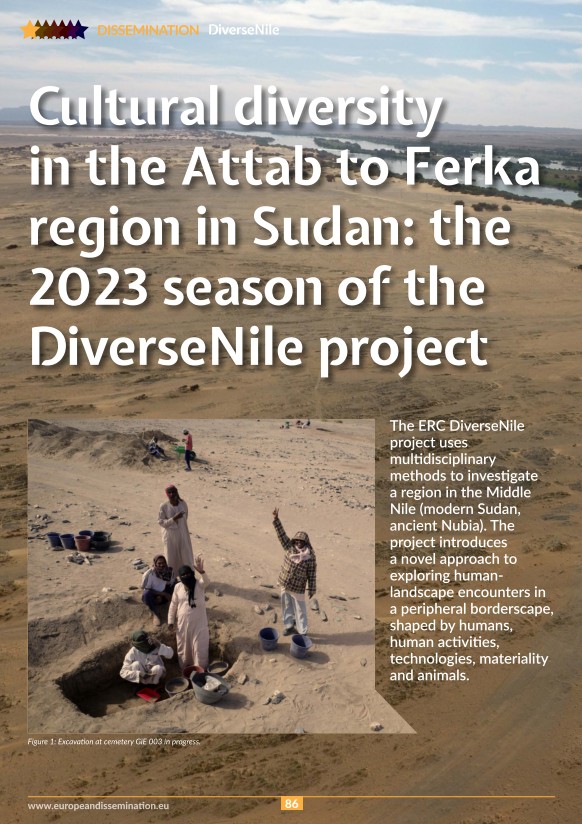

An update of our work in Kerma cemetery GiE 003 can be found in the article, highlighting the relevance of the Pan-Grave burials we discovered in Trench 5. The presence of cultural diversity (Pan-Grave Nubians, Kerma Nubians) and evidence for cultural exchange (with the Hyksos – see for example the royal scarab, with the Egyptians – especially through imported ceramics) is of key importance for the ERC DiverseNile Project.

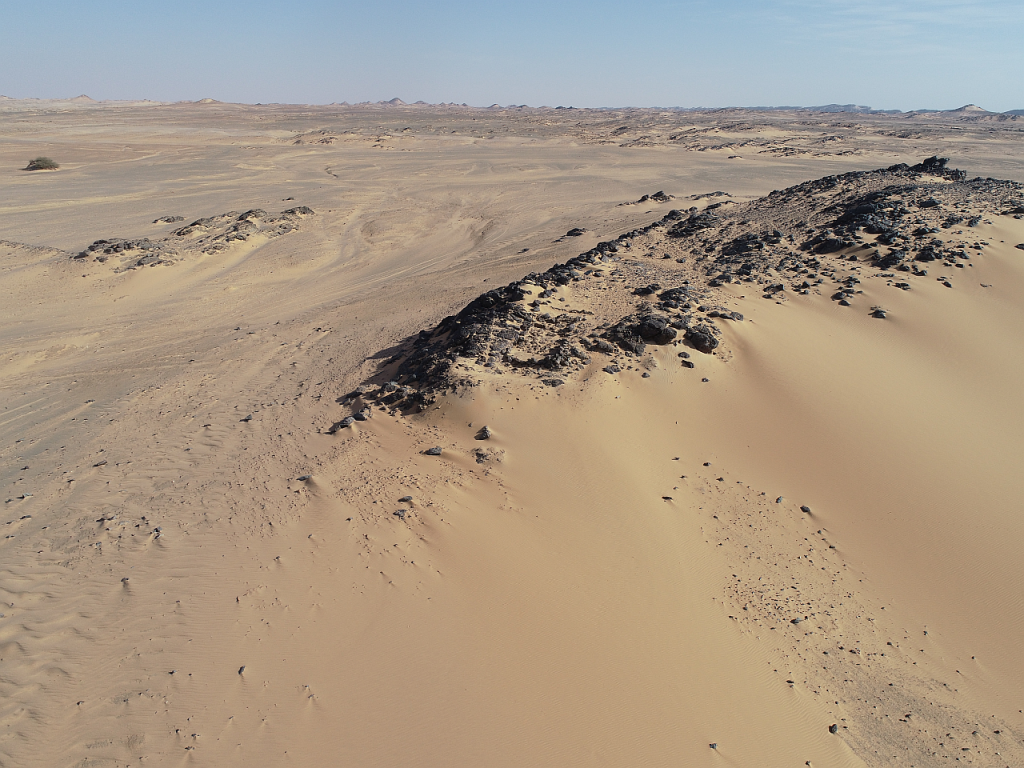

Furthermore, a short section describes our work at site 2-S-54 which we recorded as AtW 002. The rectangular Structure 1 on this site can be dated through the ceramics to the early 18th Dynasty and I included in the new article the results from the C14 analysis of a charcoal sample from a fireplace in the lower stratum, presumably the primary usage horizon. The sample yielded with the highest probability the period of 1688-1517 BCE, supporting our hypothesis that AtW 002 and neighbouring sites were probably used from Classic Kerma times to the early New Kingdom. The site is located along a paleochannel which was documented in our 2023 season by Kate (who also describes her work in this article). This paleochannel was recently addressed by our colleagues Mat Dalton, Neal Spencer and others (Dalton et al. 2023) under the topic of the intriguing river walls (of which there are plenty in our concession).

The report includes an update on our 2023 excavation at AtW 001 which allows a better understanding of this site, also in terms of dating. The material found in the debris layers we excavated in 2023 is all mid-18th Dynasty in date, therefore an abandonment of the site under the late years of Thutmose III or one of the subsequent Egyptian kings is likely. The latest pottery found at the site seems to date to the reigns of Amenhotep II/Thutmose IV (e.g. imported bichrome decorated ware).

Finally, Kate describes in the article the two primary objectives carried out for the landscape work package during the 2023 field season: 1) the drone survey over the entire district of Attab West and other areas in the concession, including low flights over selected sites for the creation of detailed orthophotos and digital elevation models of the terrain, and 2) ground survey and mapping of dry-stone features in the landscape, using a Trimble Catalyst GPS receiver, and a TDC 6000 data collector. One of Kate’s nice drone photos also made it to the cover of the new issue of MittSAG!

Seeing results of our fieldwork in Sudan published is very ambivalent at the moment – it reminds us all too well of our friends and colleagues on site and the terrible situation in Sudan, which unfortunately continues to escalate. The hope remains that 2024 will bring rapid improvement for the country and its residents. Just as there will hopefully be peace in other parts of the world.

Reference

Dalton et al. 2023 = Dalton, M., Spencer, N., Macklin, M. G., Woodward, J. C., & P. Ryan. “Three thousand years of river channel engineering in the Nile Valley.” Geoarchaeology, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21965.