I have thought a lot about style recently ‒ on the one hand about stylistic questions of Ptolemaic coffins for the Ankh-Hor project, as well as for class preparation about Egyptian art, but of course also during the processing of ceramics from Nubia, from the colonial town of Sai Island.

Style is in general a much-disputed label in archaeology and art history. Recent studies have introduced a focus on “style as effect” (Bussels and van Oostveldt 2020, 221 with references), stressing the transformative power of style and discussing style together with objects and agency. Stylistic variations as reflections of intercultural exchange seem to be very evident in the ceramic corpus from colonial Nubia during the New Kingdom.

It is well established that are clear differences regarding the Egyptian style and the Nubian style pottery corpora in colonial Nubia, not only in terms of shape but also regarding the technology with wheel-made Egyptian and hand-made Nubian vessels. From the beginning of my study of pottery from Sai Island, I used the term “Egyptian style” for wheel-made products and soon differentiated between locally produced variants and imported vessels.

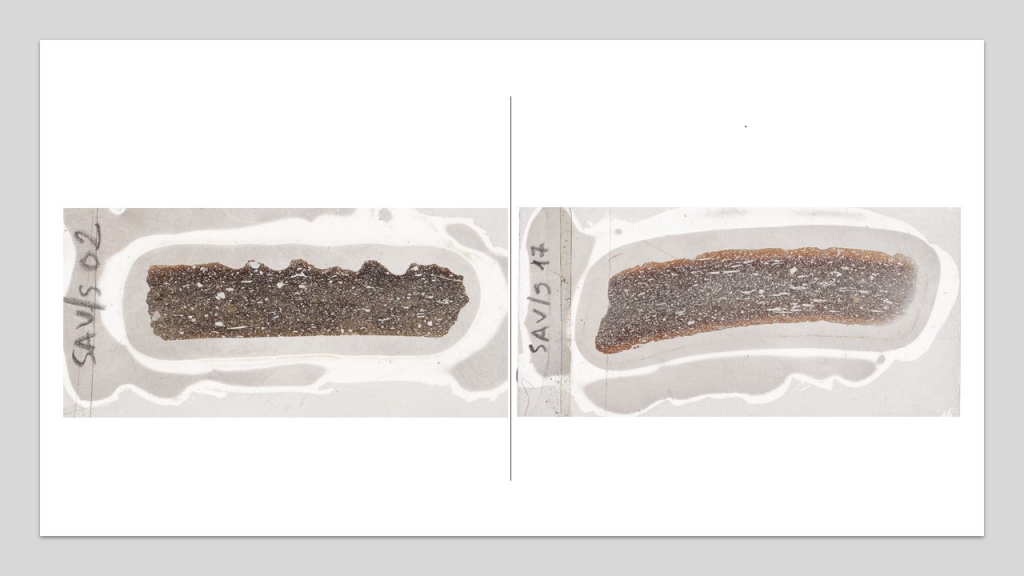

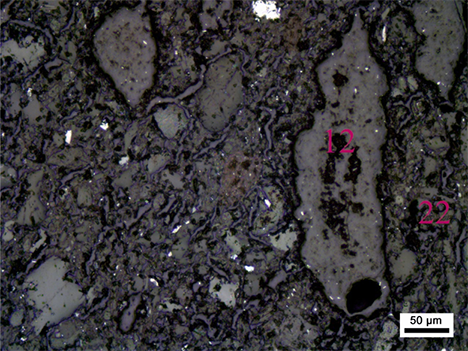

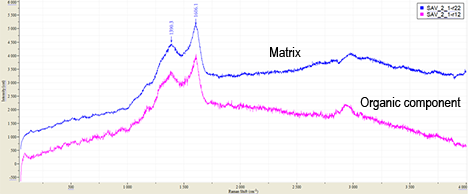

But let’s come back to the broad concept of style – I believe the main aim should be to address the complex processes involved in producing objects (as proposed by Marian Feldman 2006 for the “International Style” of the Late Bronze Age). My labels for New Kingdom pottery in Nubia also stress the production process – vessels which appear within the Nubian respectively in the Egyptian tradition, without marking them already as Nubian or Egyptian production. Of interest is the effect and the role these objects took in the framework of cultural encounters – sometimes taking hybrid forms, making it impossible to separate the distinctive traditions from each other. Hybrid pottery products from colonial Nubia must be regarded as something new and separating Egyptian and Nubian elements on these pots is not helpful or applicable. Giulia D’Ercole is currently working within the DiverseNile project on these hybrid products and their significance for cultural encounters, focusing on the production technique including the raw materials.

Within New Kingdom Nubia, regional style in ceramics was mostly expressed by surface treatment and decoration (see already Miélle 2014). One exceptional case is that the colonial experiences on Sai resulted in a new style of painting wheel-made ceramics. Deep bowls are attested in all sectors of the town and find parallels in Askut. Stuart Tyson Smith interpreted the preference of wavy lines and painted triangles on these bowls as local Nubian style (Smith 2003, fig. 3.7). Laurianne Miellé concentrated on the pending triangles painted in black on red and which seemingly refer to earlier Nubian decoration patterns known from C-Group vessels and Kerma Moyen bowls (Miélle 2014, 387‒389, fig. 4). However, this is not simply an inspiration by means of motif but there was a striking transformation in the execution style – incised decoration was carried out as painted decoration. Here, the colouring scheme seems to have been influenced by the new black-on-red style which became fashionable in the early 18th Dynasty, both in Egypt and New Kingdom Nubia. The shapes are markedly different from any Nubian style vessels and typically Egyptian; the production technique is also Egyptian, but in local variants of Nile clays. All in all, this new style of painted vessels must be seen as the embodiment of colonial experiences, transforming different cultural traditions to something new with multiple affinities in both directions.

Just as one example, this mixed context of sherds from sector SAV1 West in the colonial town of Sai shows the multiple styles of pottery we typically encounter in this urban centre with a strong cultural diversity in its material culture. There are imported Marl clay vessels from Egypt, one of which is painted and could be labelled as „Levantine style“ (although an Egyptian product); there are two bichrome decorated Nile clay vessels which were maybe produced locally in Nubia, but are very similar in style to Marl clay vessels and Nile clay vessels known from Egypt (see Budka 2015); one example attests the wheel-made painted bowls which seem to express a very specific colonial Nubian style restricted to Nubia (but here the style of painting is less clearly inspired by Nubian incised decoration). And finally, there is an undecorated, wheel-made dish produced locally on Sai and the rim sherd of a Kerma Classique beaker, probably also manufactured locally (and not imported from the Third Cataract region).

Sai is clearly another case study for a distinctive “local variation within a generally shared repertoire of material culture” (Näser 2017, 566) commonly found in New Kingdom Nubia which originates from specific social practices (Lemos 2020). Within the DiverseNile project and with our contact space biography approach, also considering the concept of Objectscapes, I believe we can take the results from Sai further. One aspect I will be working on in the next weeks is whether the intriguing concept of “Communities of Style” (Feldman 2014) is applicable to questions about pottery production in colonial Nubia, first of all for Sai and its hinterland, the MUAFS concession area.

References:

Bussels and van Oostveldt 2020 = Stijn Bussels and Bram van Oostveldt, Egypt and/as style, in: Miguel John Versluys (ed.), Beyond Egyptomania: objects, style and agency, Berlin/Boston, 219–224.

Budka 2015 = Julia Budka, Bichrome Painted Nile Clay Vessels from Sai Island (Sudan), Bulletin de la céramique égyptienne 25, 331–341.

Feldman 2006 = Marian Feldman, Diplomacy by Design. Luxury Arts and an ‚International Style‘ in the Ancient Near East,1400-1200 BCE, Chicago.

Feldman 2014 = Marian Feldman, Communities of Style : Portable Luxury Arts, Identity, and Collective Memory in the Iron Age Levant, Chicago.

Lemos 2020 = Rennan Lemos, Material Culture and Colonization in Ancient Nubia: Evidence from the New Kingdom Cemeteries, in: Claire Smith (ed.), Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3307-1.

Miélle 2014 = Laurianne Miélle, Nubian traditions on the ceramics found in the pharaonic town on Sai Island, in: Julie R. Anderson and Derek A. Welsby (eds.), The Fourth Cataract and Beyond. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies, British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 1, Leuven, 387–392.

Näser 2017 = Claudia Näser, Structures and realities of the Egyptian presence in Lower Nubia from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom: The Egyptian cemetery S/SA at Aniba, in: Neal Spencer, Anna Stevens and Michaela Binder (eds.), Nubia in the New Kingdom. Lived experience, pharaonic control and indigenous traditions, British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 3, Leuven, 557‒574.

Smith 2003 = Stuart Tyson Smith, Pots and politics: Ceramics from Askut and Egyptian colonialism during the Middle through New Kingdoms, in: Carol A. Redmount and Cathleen A. Keller (eds.), Egyptian Pottery. Proceedings of the 1990 Pottery Symposium at the University of California, University of California Publications in Egyptian Archaeology 8, Berkeley, 43–79.