It’s been a few weeks since our fantastic weekend full of experimental archaeology at Asparn (Austria), at the MAMUZ museum. I have tried to summarise the first part of our experiments, producing Nile clay vessels including the firing process with animal dung, in a previous blog post.

Once again, loads of thanks go to all our dear friends and colleagues who supported us – Vera Albustin, Ludwig Albustin, Michaela Zavadil and Su Gütter – as well as to the Viennese hosts of the event, especially to Mathias Mehofer.

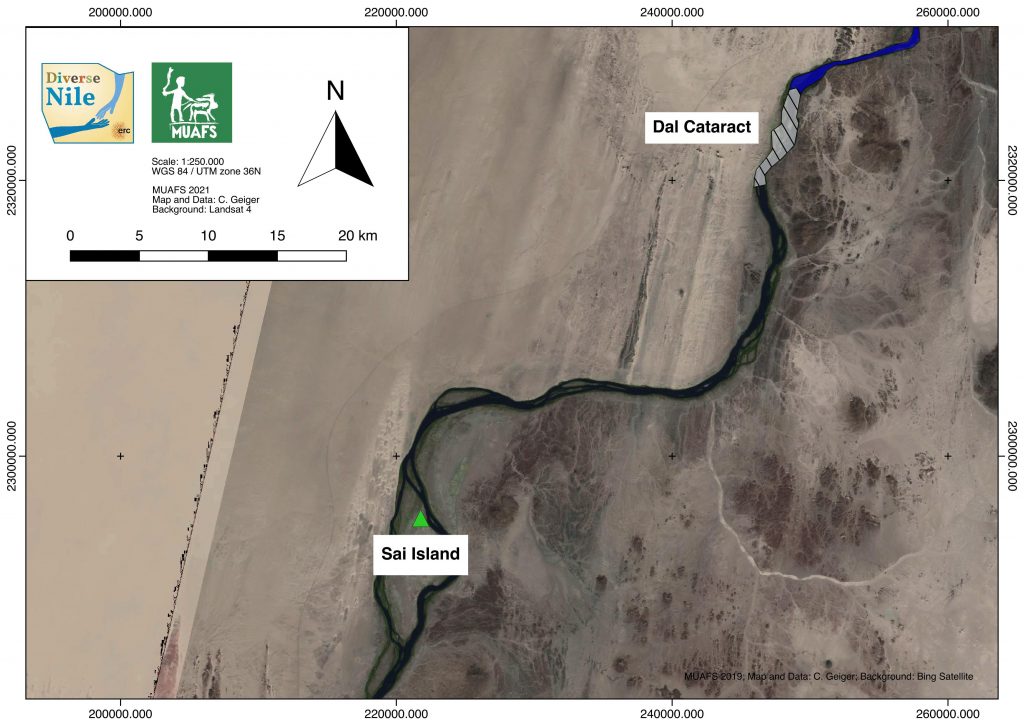

The second part of our experiments was dedicated to cooking with fire dogs – a topic which keeps us busy ever since our work at Sai Island and the discovery of large amounts of fire dogs in the New Kingdom town. We have produced a number of replicas of fire dogs in the last years – and have tested various settings and arrangements of fire dogs to hold a cooking pot above the fire.

This year, we tested a new arrangement – placing two fire dogs in our pit to hold a Nubian-style cooking pot. Other than normally reconstructed (following a seminal paper by D.A. Aston), we placed the fire dogs upside down – with the “ears” to the top, using these as support for the pot.

Well – the preparation of red lentils was absolutely problem-free – we used some wood as fuel as well as cattle dung. The fire dogs held the pot next to the fire, allowing us to reduce or increase the temperatures upon need.

Our replicas of fire dogs include examples with “snouts” as well as with “handles”, just like the Sai originals. For our cooking experiment this year, we used two examples with handles and placed the handle away from the fireplace. And: at the end of the cooking process, we could use the handles to take the fire dogs straight out of the fireplace and use them as a support for the pot while we were eating. Could this maybe be the explanation for these parts of our curious fire dogs?

We will continue to experiment with our fire dog replicas – not least because one of our new settlement sites in the MUAFS concession in Sudan, AtW 001, yielded several fire dogs from 18th Dynasty contexts, providing an excellent fresh parallel for the situation at Sai Island.