We had an early and unpleasant start into the weekend – because of a strong sandstorm we needed to stop work at Thursday already before breakfast. Since we were just cleaning the human remains in the first tomb we found at GiE 002 and discovered a second pit burial, this was indeed unfortunate.

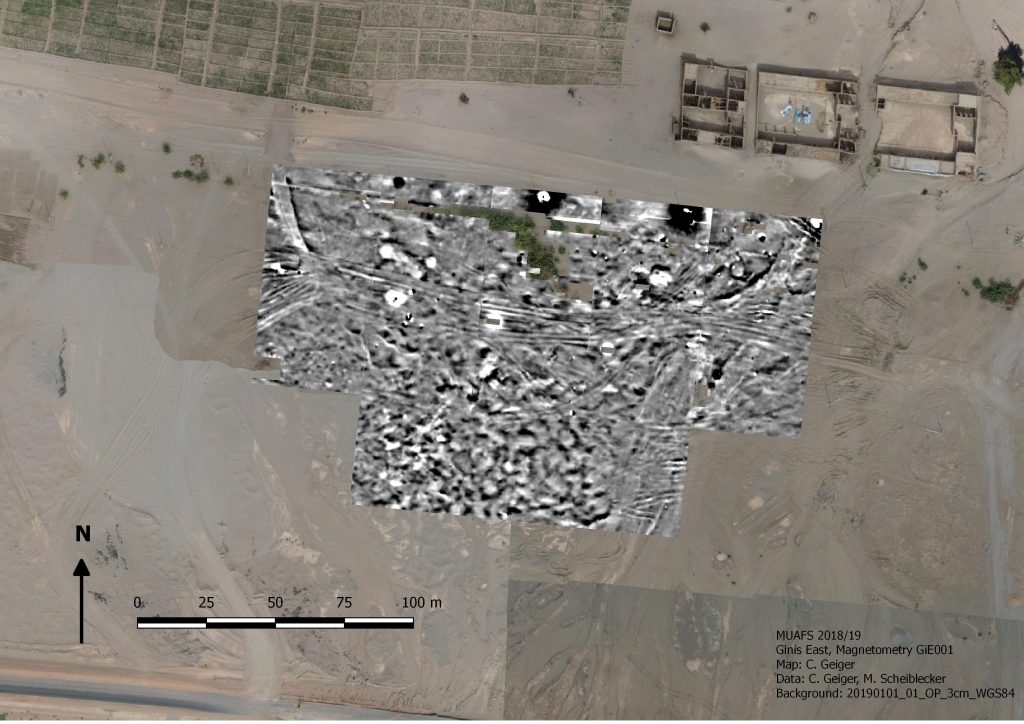

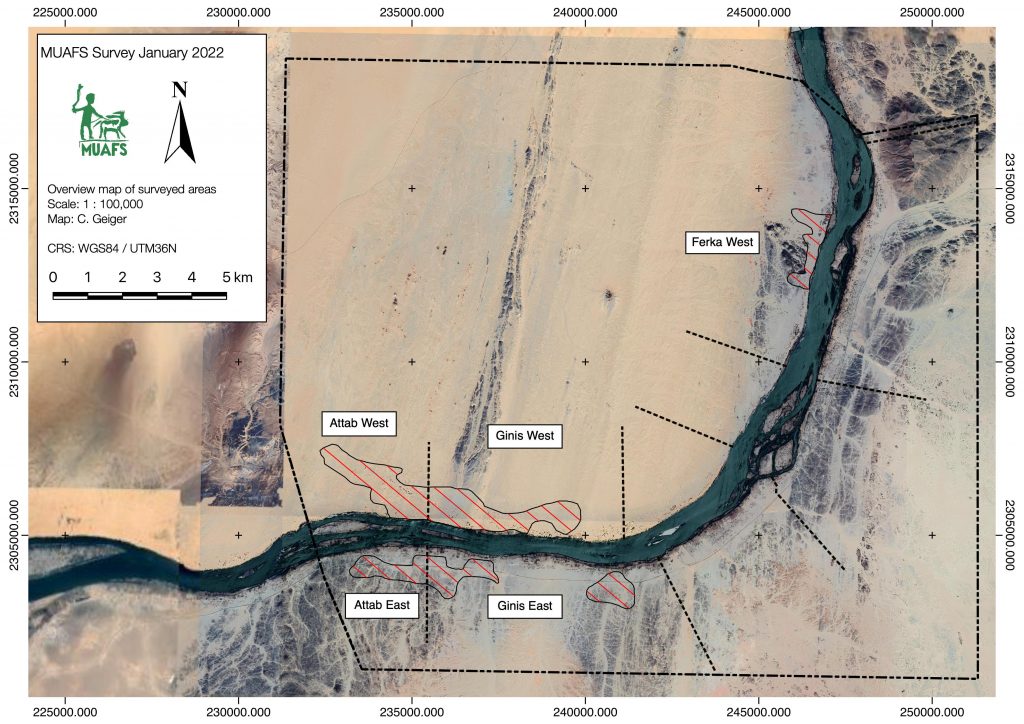

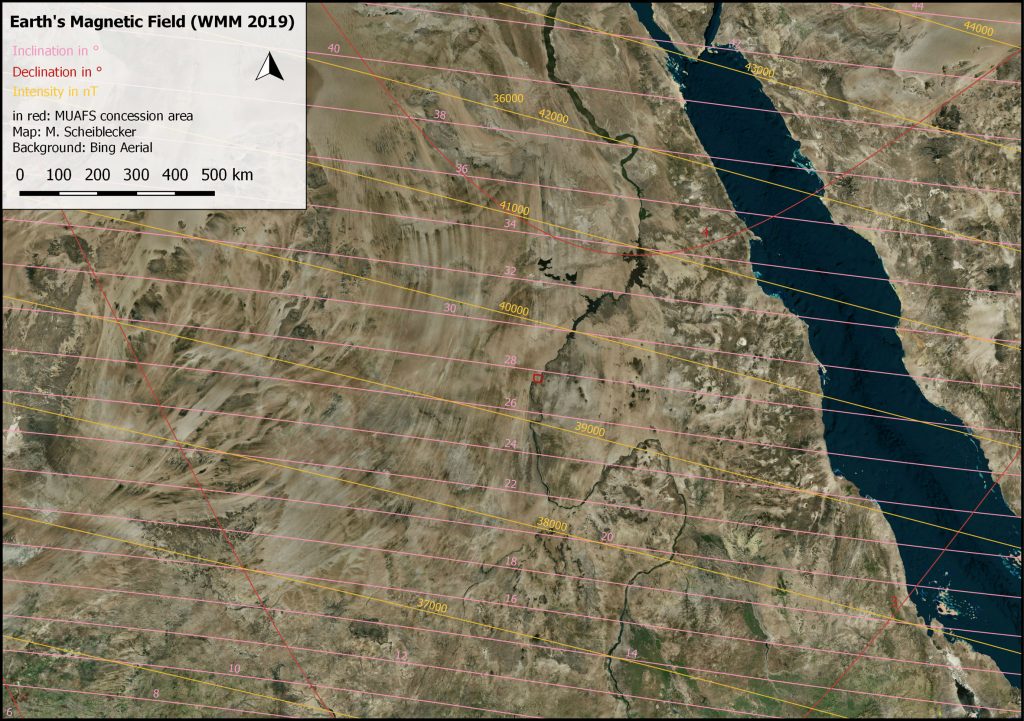

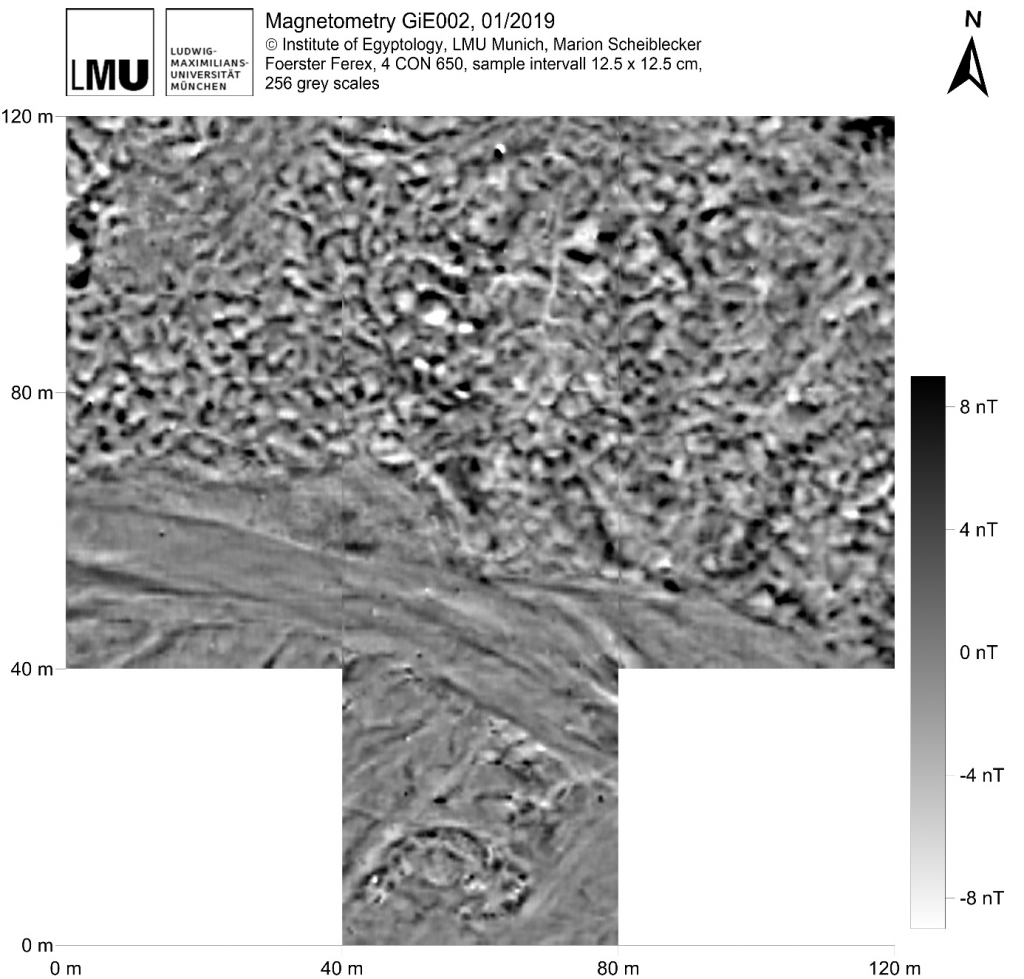

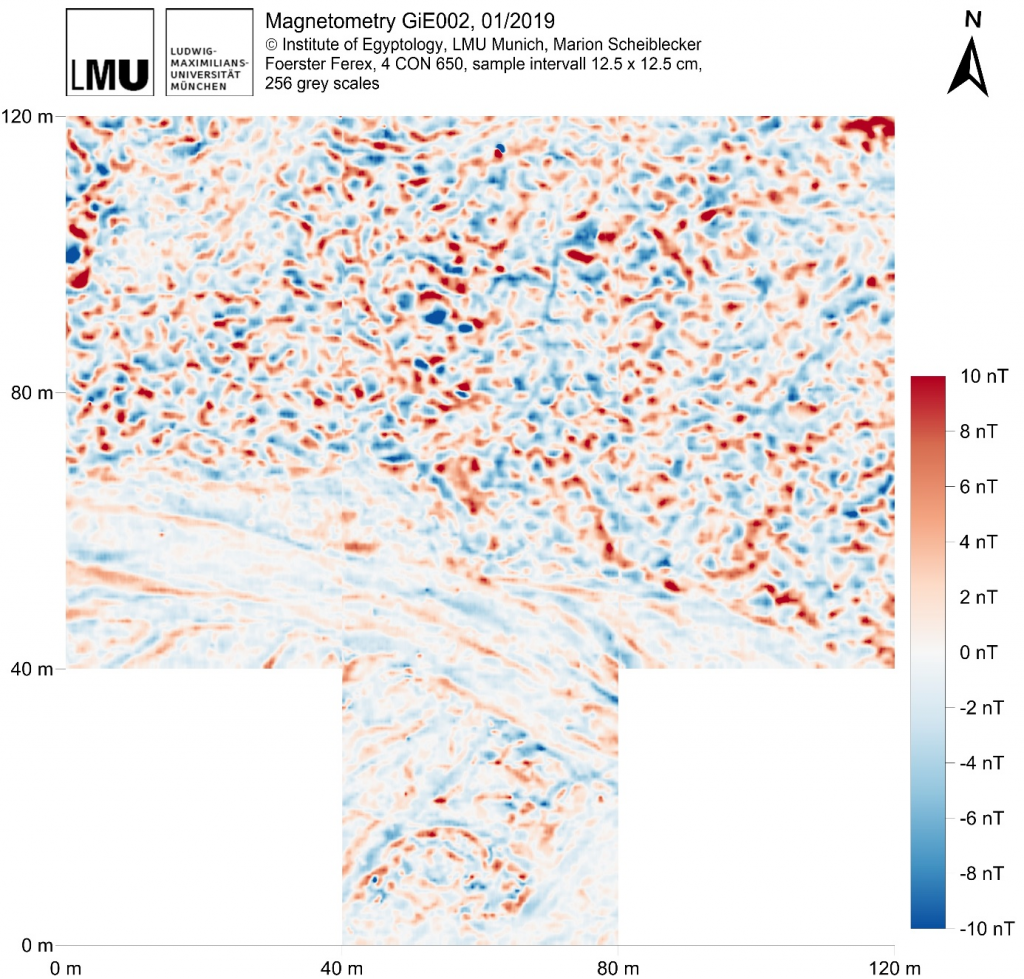

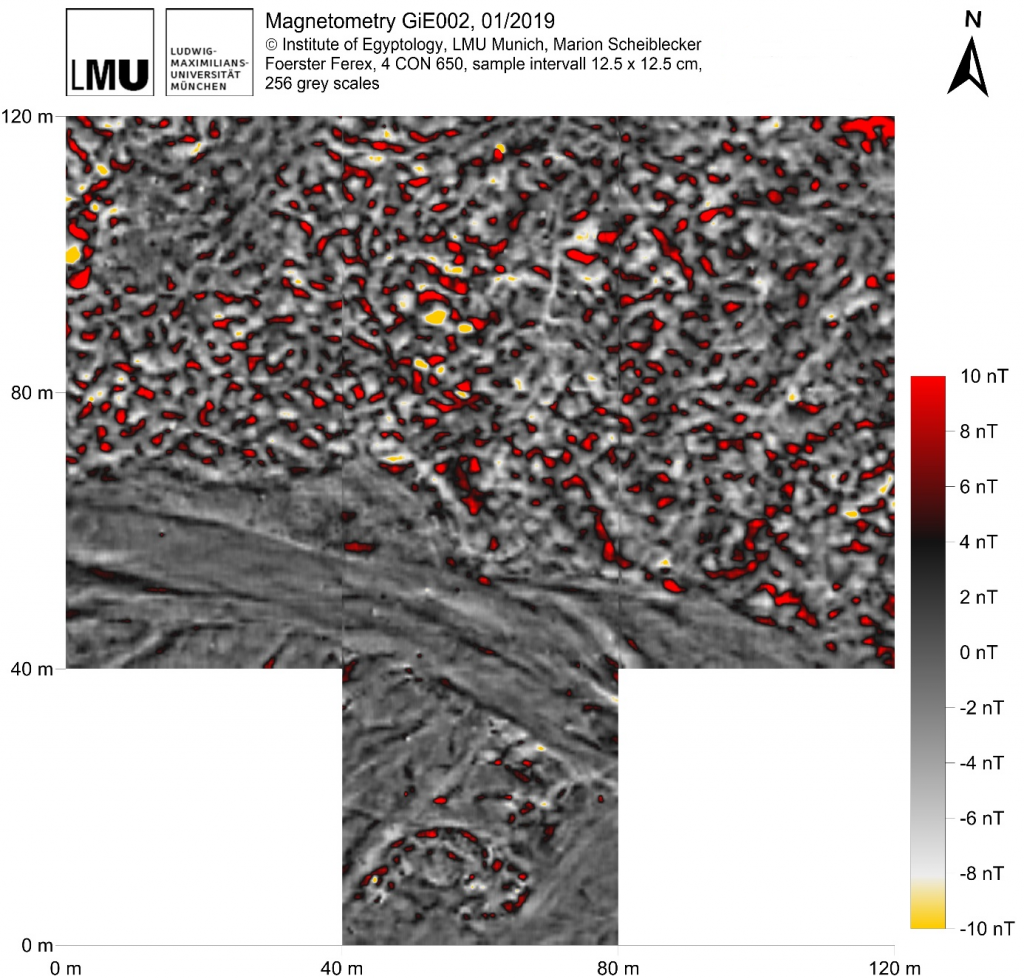

However, the first week of our 2022 was intense and in many respects successful. Part of this success might not seem very positive at the first glance, but is nevertheless of much relevance for the project. We stopped work at the settlement site GiE 001 already after 4 days. We did not succeeded in finding archaeological features at this site, but we confirmed my earlier impression about this site based on the results from the two test trenches we opened in 2020 (Trench 1 and 2`, Budka 2020, 66-67). With one large area (Fig. 1) and one small test trench (Fig. 2) we now know for sure that a thin sandy surface layer with finds from various periods – Kerma, 18th Dynasty, Ramesside, Napatan and Medieval – is directly on top of natural alluvial layers. No archaeological stratigraphy or sediments are preserved. Our magnetometry from 2018/2019 does not show any archaeological features but simply differences in the soil (e.g. sandy areas).

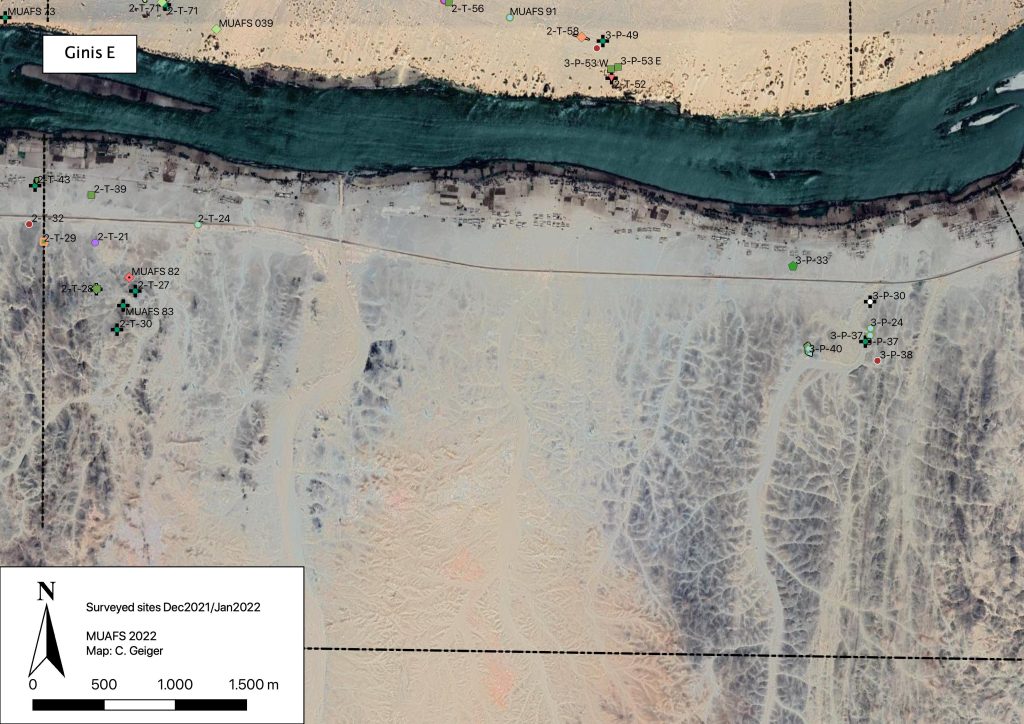

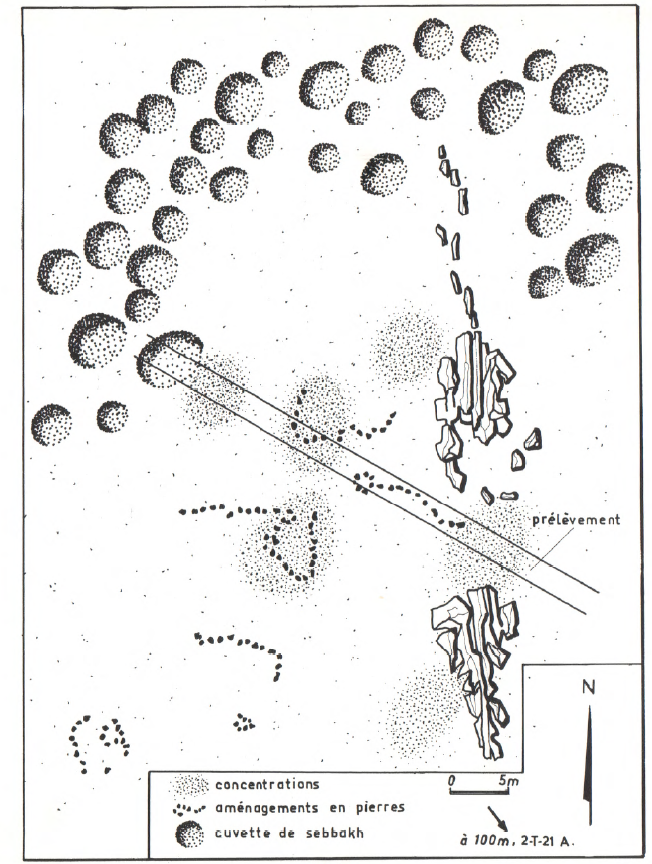

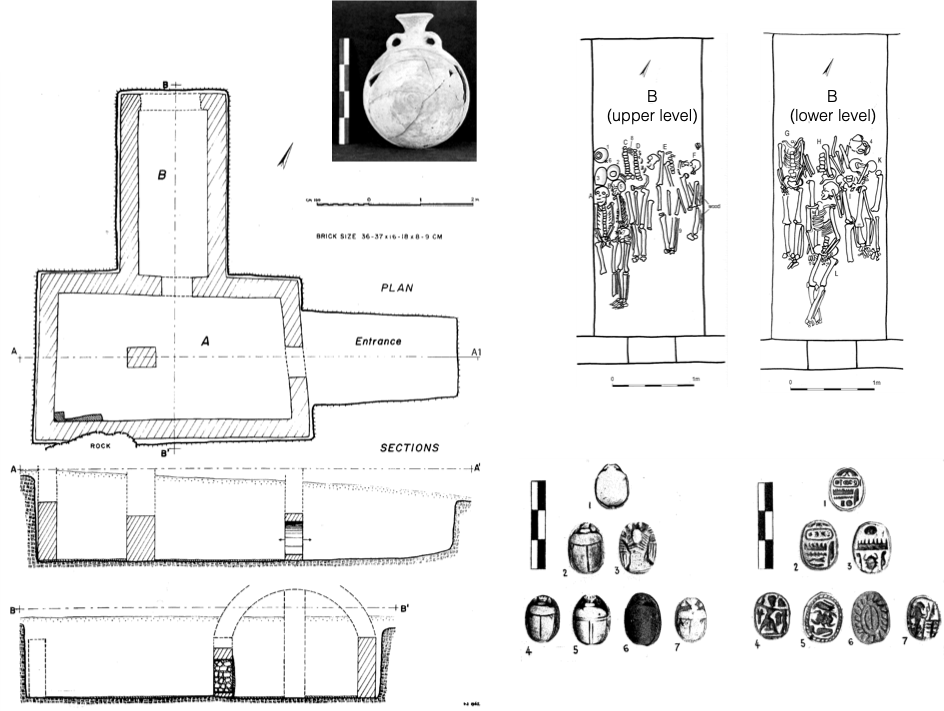

With this confirmed, we moved on Wednesday to cemetery GIE 002 just a bit further south. Here, the main aim was finding some tombs to check the dating as proposed by Vila in the 1970s. He dated the small cemetery with largely dismantled stone superstructures to the New Kingdom, but already the one pit burial he excavated and its pottery vessels suggest that this is too early. A Pre-Napatan or Napatan dating would clearly fit much better.

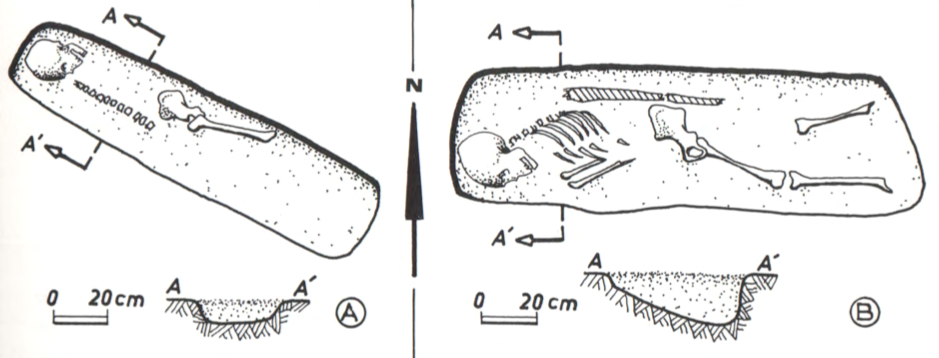

This is now getting more and more likely after just 1.5 days of work – we discovered two tombs of the pit burial type as described by Vila (site 2-T-13) and all of the associated ceramics seem to postdate the New Kingdom.

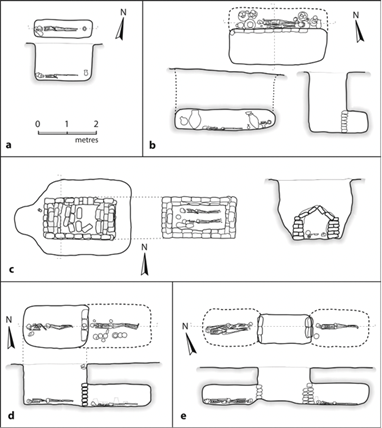

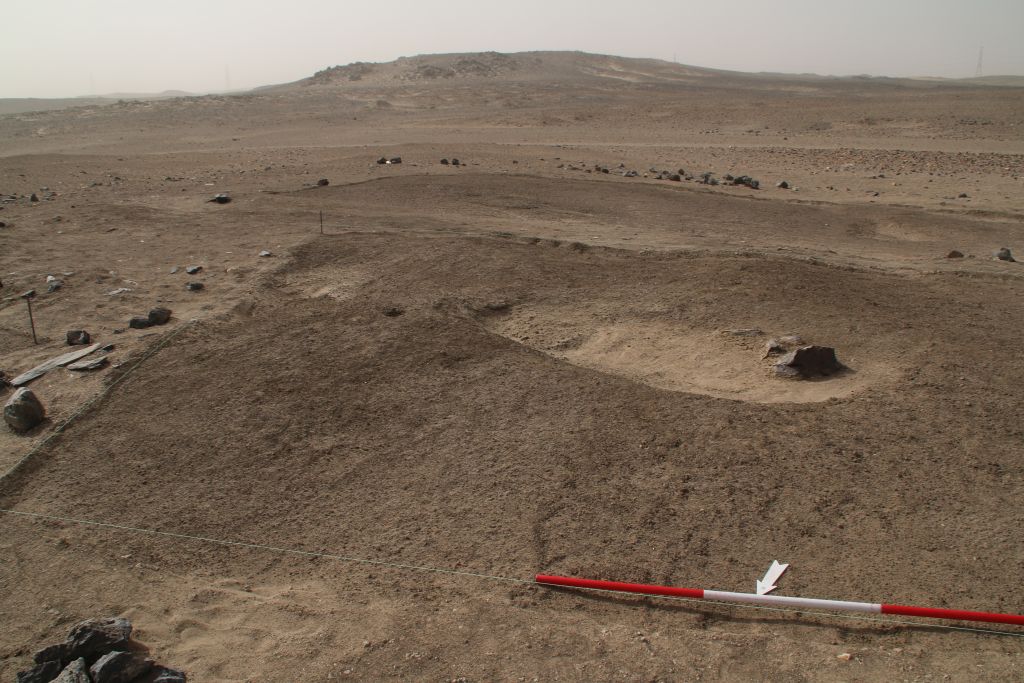

First, we opened a large area where we thought depressions of three tombs are visible on the surface (and on the magnetometry, Fig. 3). The result was a bit surprising, only one tomb in the eastern part was found (Fig. 4).

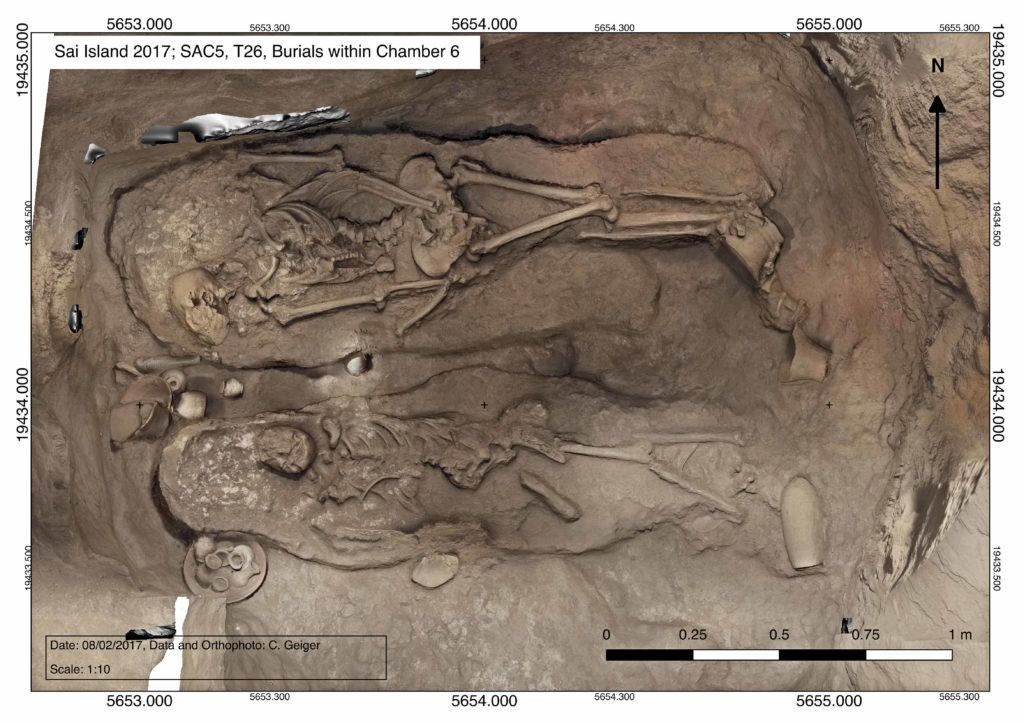

In the sandy filling of this burial pit, we have a minimum of one adult burial in displaced position (Fig. 5). Because of the sandstorm, we did not yet finish excavations and still need to clean the pit. Since Vila found the remains of seven individuals in a similar burial pit (Vila 1977, 48, fig. 16), I expect more human remains closer to the bottom.

Two other areas in GiE 002 yielded no burials at all, but Trench 4 finally comprised another pit burial filled with windblown sand (Fig. 6). We also started work in another area (Trench 5) but had to stop there because of the storm. Thus, with a minimum of two pit burials to be excavated we will be able to reassess this site – please keep your fingers crossed that the tombs also include some diagnostic pottery!

In our first week, the division of work within the team worked out perfectly. Max and Fabian from Novetus were documenting all trenches at GiE 001 and GiE 002, Iulia was responsible for writing find labels and the consecutive find list. Our inspector Huda helped with supervising the workmen and our driver Imad was helpful in many respects. All of them, our wonderful gang of Sudanese workmen included, did a great job and I am very much looking forward to the results of the upcoming week.

References

Budka 2020 =J. Budka, Kerma presence at Ginis East: the 2020 season of the Munich University Attab to Ferka Survey Project, Sudan & Nubia 24, 2020, 57-71.

Vila 1977 = A. Vila, La prospection archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise). Fascicule 5: Le district de Ginis, Est et Ouest. Paris 1977.