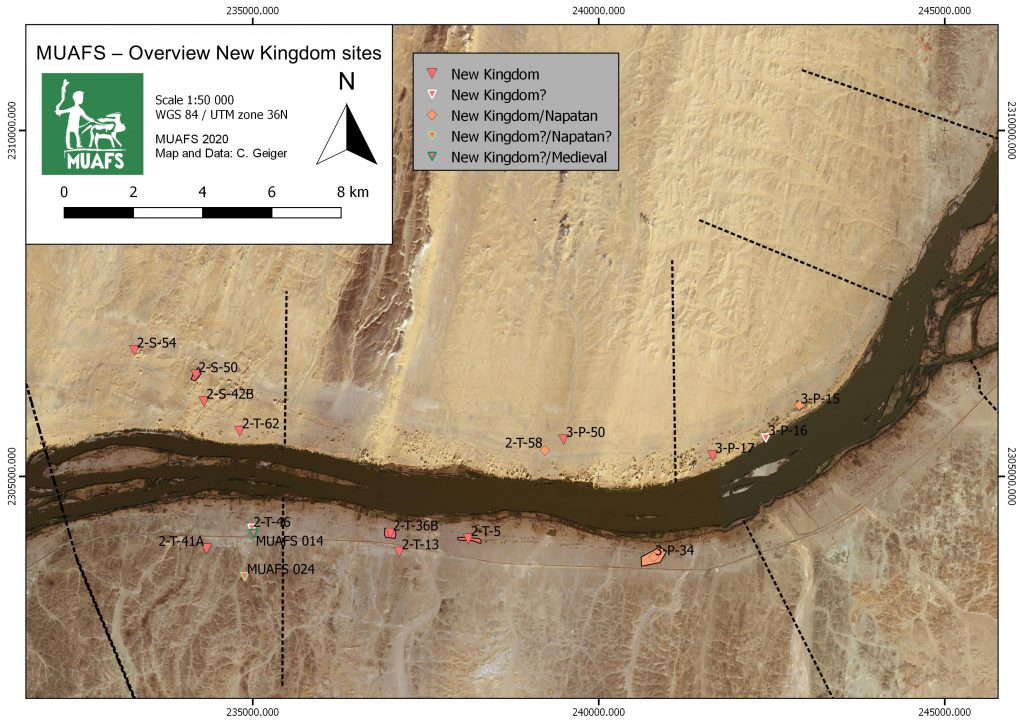

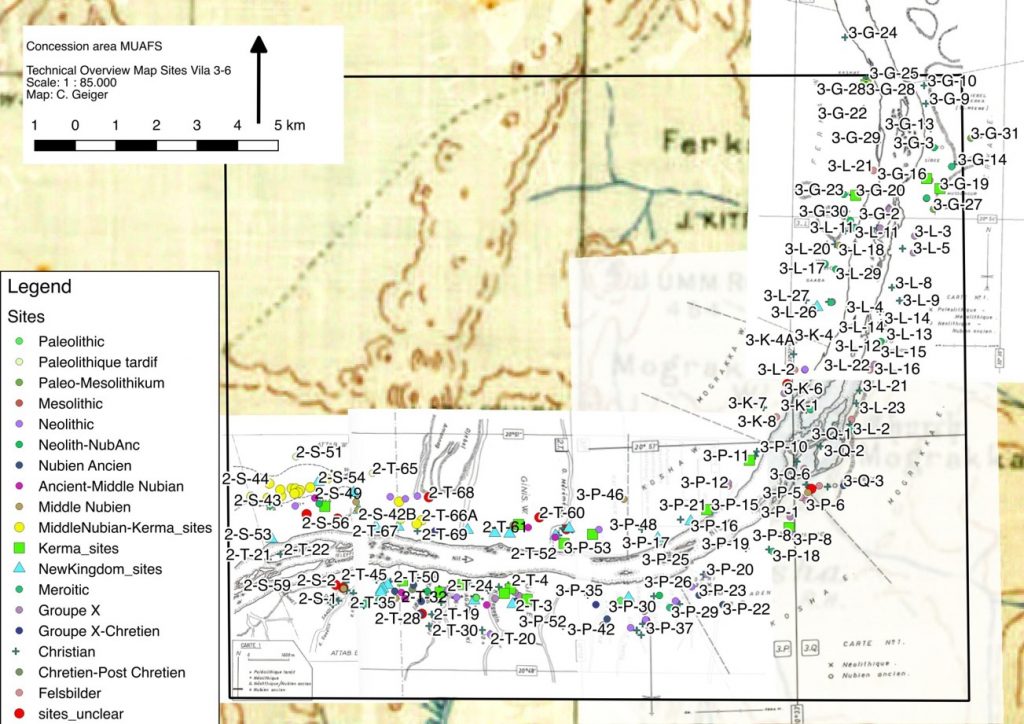

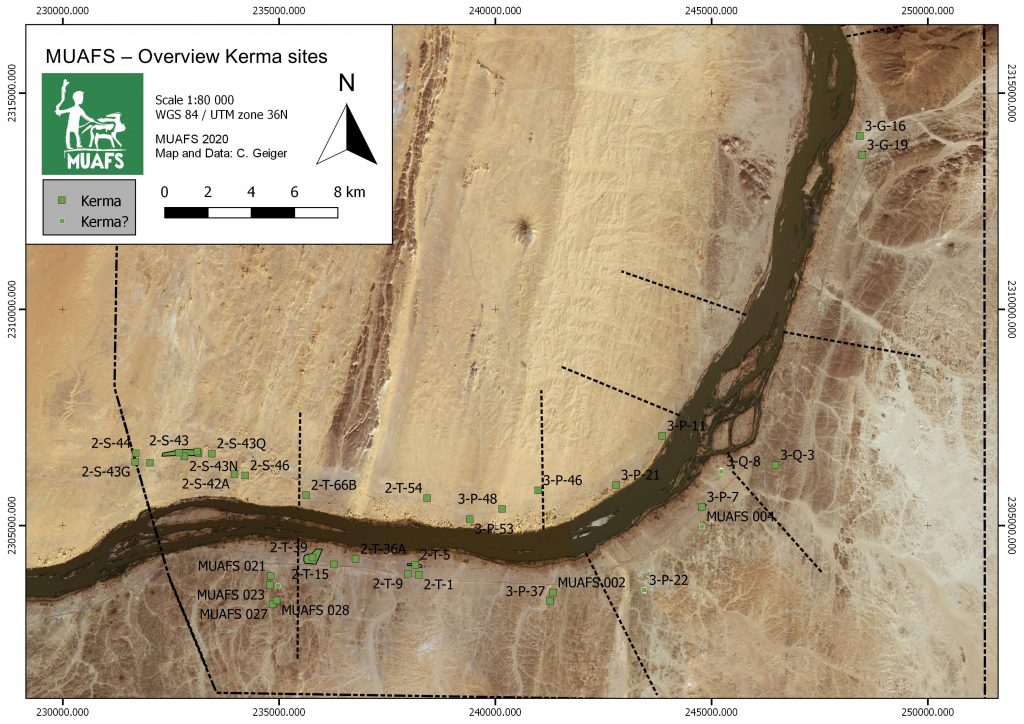

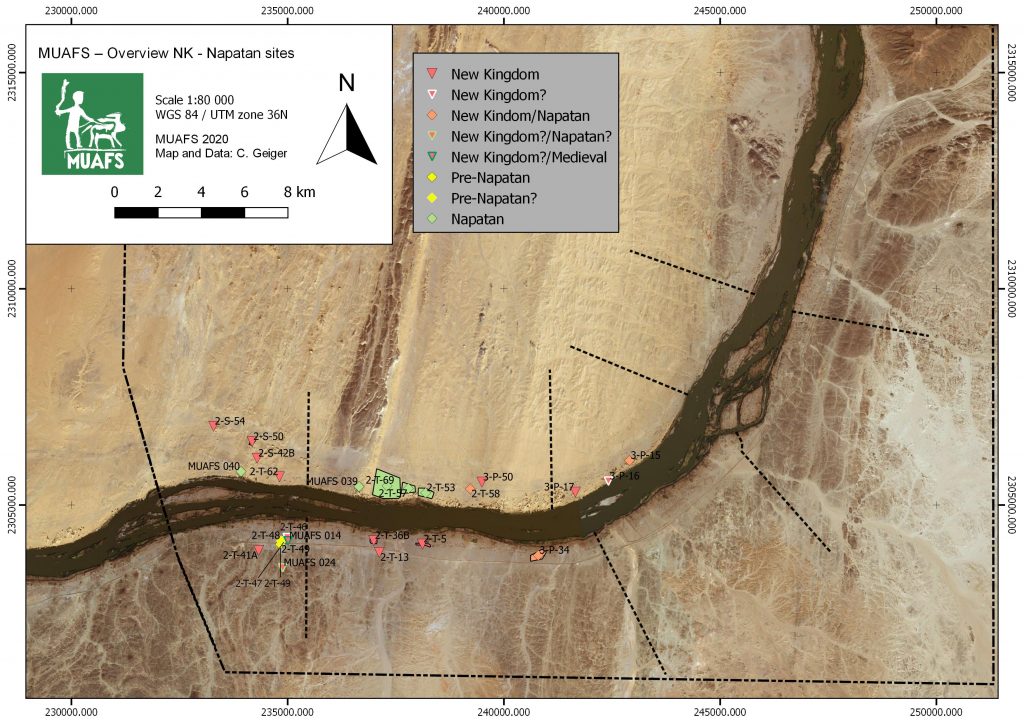

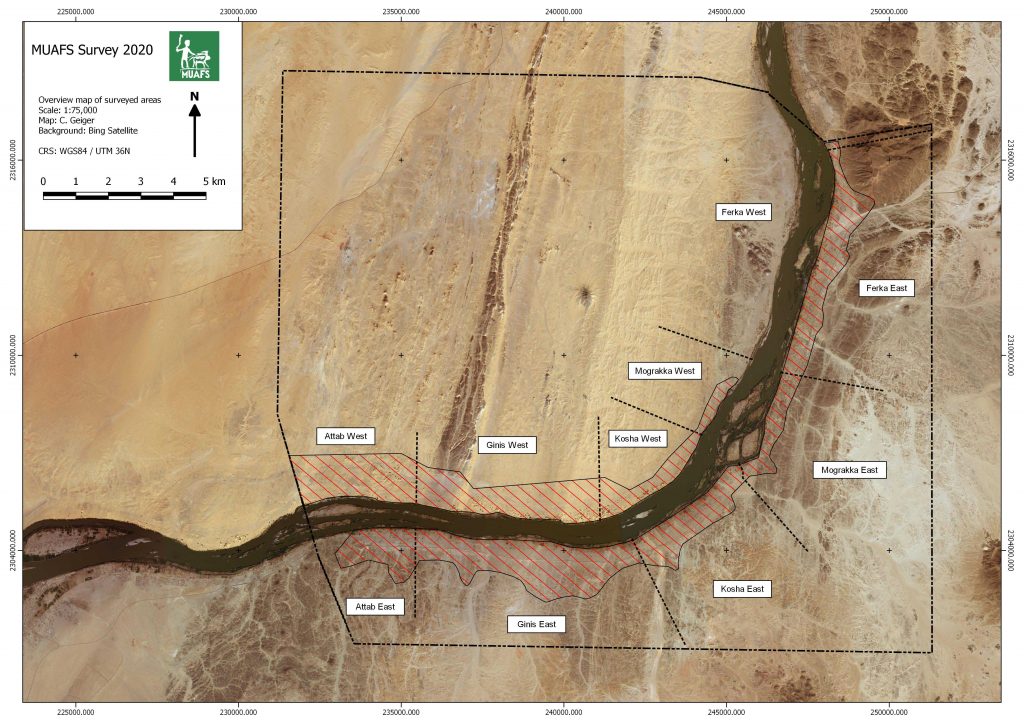

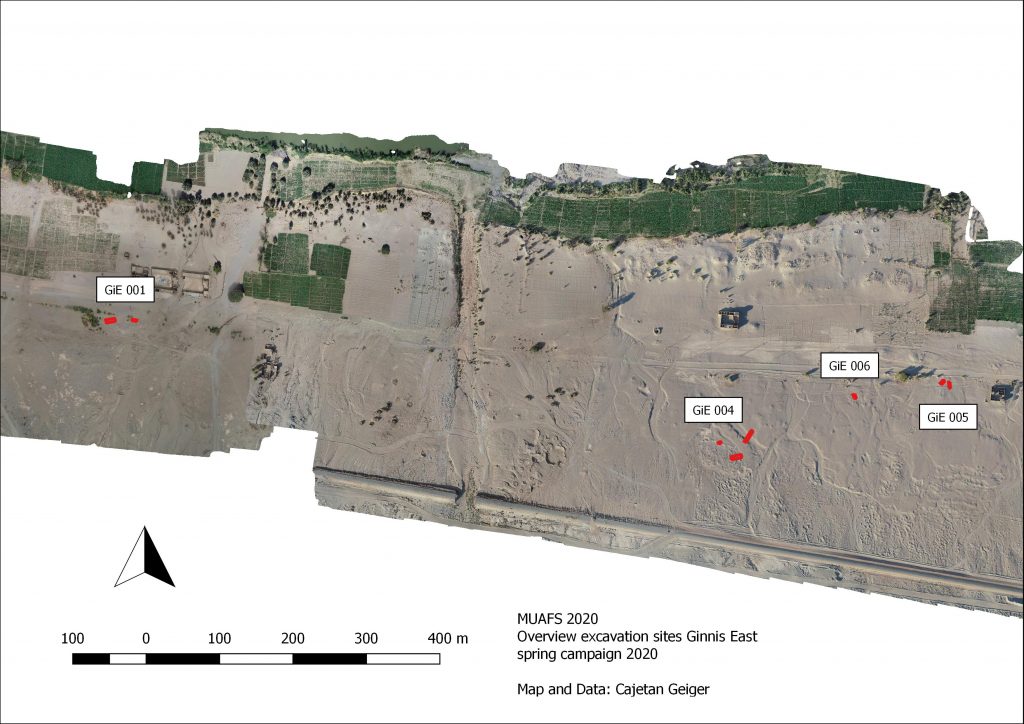

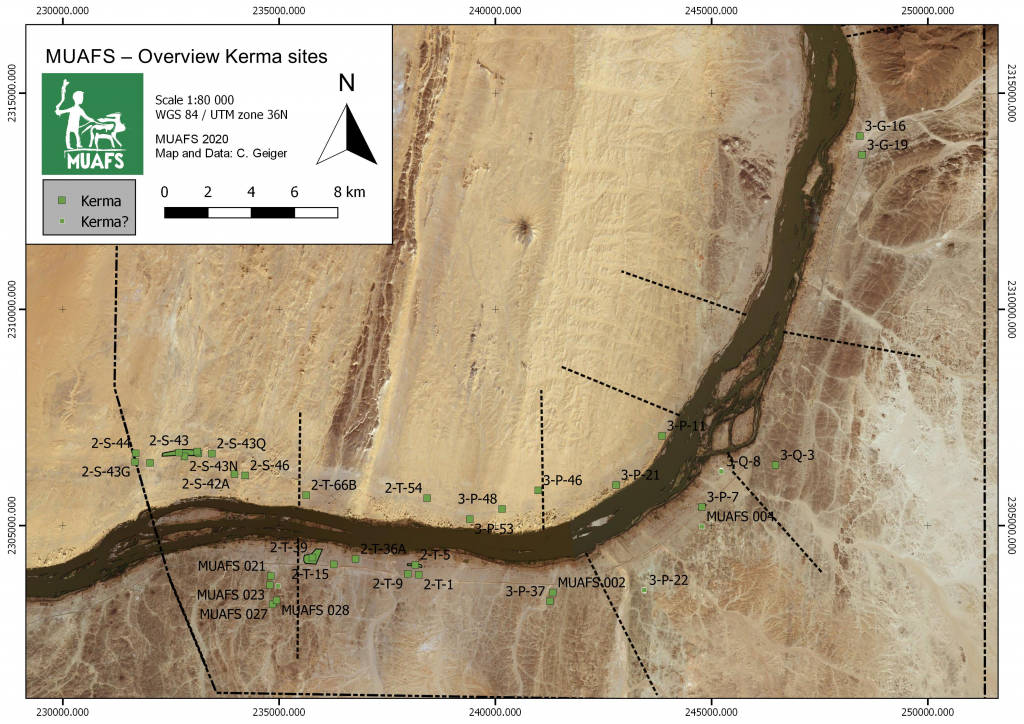

Sudan & Nubia 24 is now out and it includes a paper by PI Julia Budka on the Kerma presence at Ginis East (Budka 2020). The paper also presents an updated overview of MUAFS fieldwork, which relates to my work in the DiverseNile Project focusing on Kerma, New Kingdom and early Napatan cemeteries in the region. In the past three seasons, the MUAFS team reidentified hundreds of sites firstly described by Vila, but also identified 40 additional sites so far, including tombs which are of interest to my subproject. In my previous posts, I have focused mainly on the New Kingdom. Here I will present a brief overview of the Kerma presence, as attested by cemetery sites and isolated tombs, in Attab-Ferka (figure 1).

I have previously mentioned that, for the New Kingdom, our knowledge is mainly based on evidence from major colonial settlements and cemeteries. There are clear geographical gaps in what we know about the Egyptian colonisation of Nubia in areas such as the Batn el-Hajjar (Edwards 2020) or the MUAFS concession area. A similar situation occurs during the Kerma Period. As Julia Budka pointed out in her recent S&N paper, evidence from Attab-Ferka is extremely relevant “to address the issue of the borders of the Kerma kingdom as well as cultural manifestations of what has been labelled as ‘rural Kerma’” (Budka 2020: 63).

Veronica Hinterhuber’s last post provided an overview of her general database of sites based on information published by Vila. Her work is invaluable for my preliminary assessment of mortuary sites in our concession area. Based on her database, 10 mortuary sites first identified by Vila as dating to the Kerma Period can help us to preliminarily understand the Kerma spread in the region. Recent fieldwork has identified a large degree of destruction and plundering at those sites, which makes it important to revisit previously published and archival data with a fresh mindset to extract valuable information. Comparison with other sites, especially those at the Kerma hinterland and other ‘peripheral’ zones across Nubia, also help us shed light onto blurred spots in our datasets from Attab-Ferka.

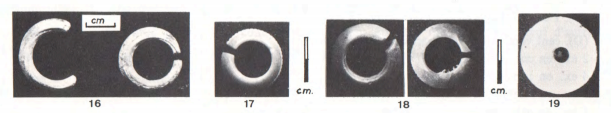

Besides the overall plundering, Kerma tombs in the region were tumuli with granite superstructures (usually not preserved) and oval or large rectangular pits containing bone fragments, sherds and very rarely burial goods (e.g., faience beads). Kerma tombs were either larger, aprioristically isolated tombs or part of cemeteries grouping a higher number of burials; e.g., at Ferka East and Kosha East. A few skeletons were found in situ, although plundered. They were all deposited in a flexed position, sometimes on a bed; e.g. at Ferka East. Kerma tombs were reused in the Christian Period. For instance, one wrapped body dating to this period was found inside a Kerma tomb at Kitfogga, Ferka East. Sherds usually include Kerma beakers and goblets. Due to plundering, it is difficult to determine, based on the amount of information currently available, whether these burials were characterised by a simple approach to graves goods or not. Comparison with sites such as Abu Fatima, where Stuart Tyson Smith and Sarah Schrader are currently working, should allow us to gain a better picture of continuity and variation in Kerma contact spaces between, for instance, elites and non-elites or urban and rural communities.

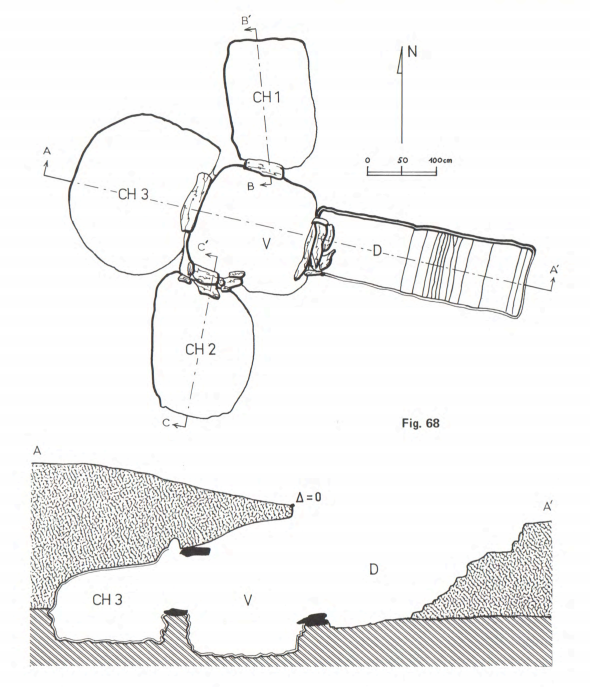

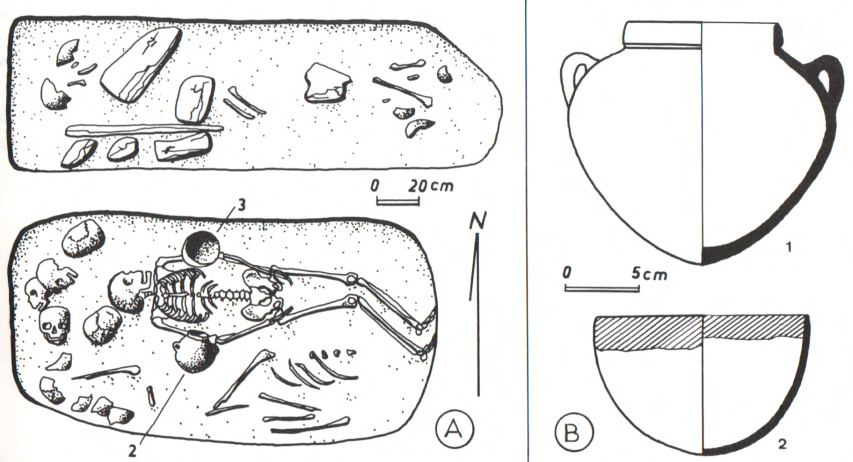

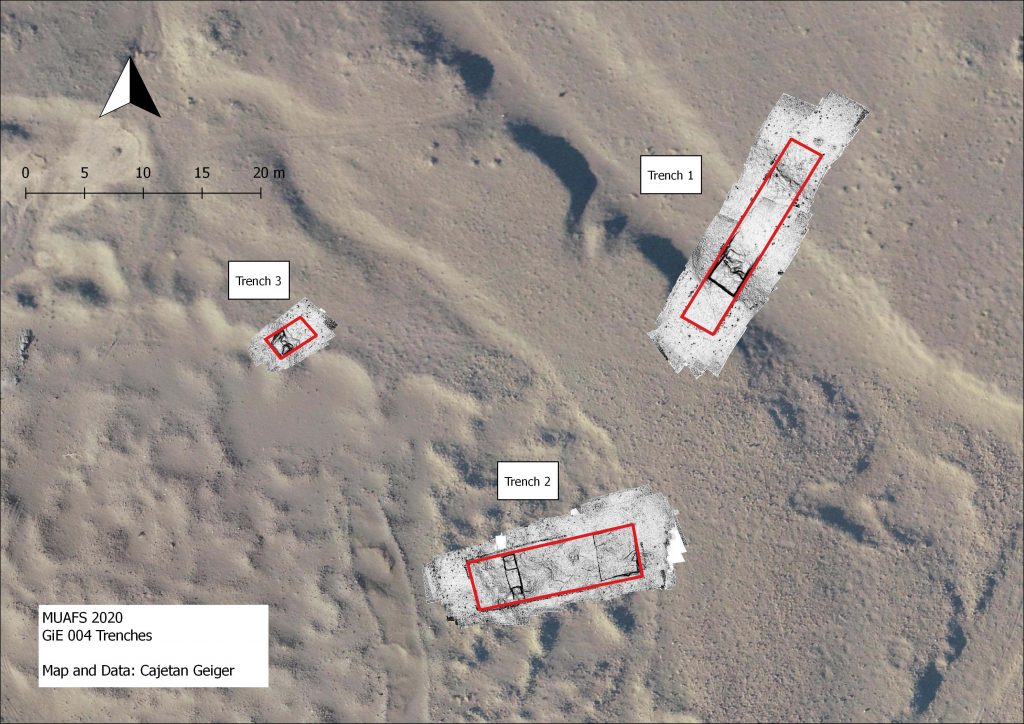

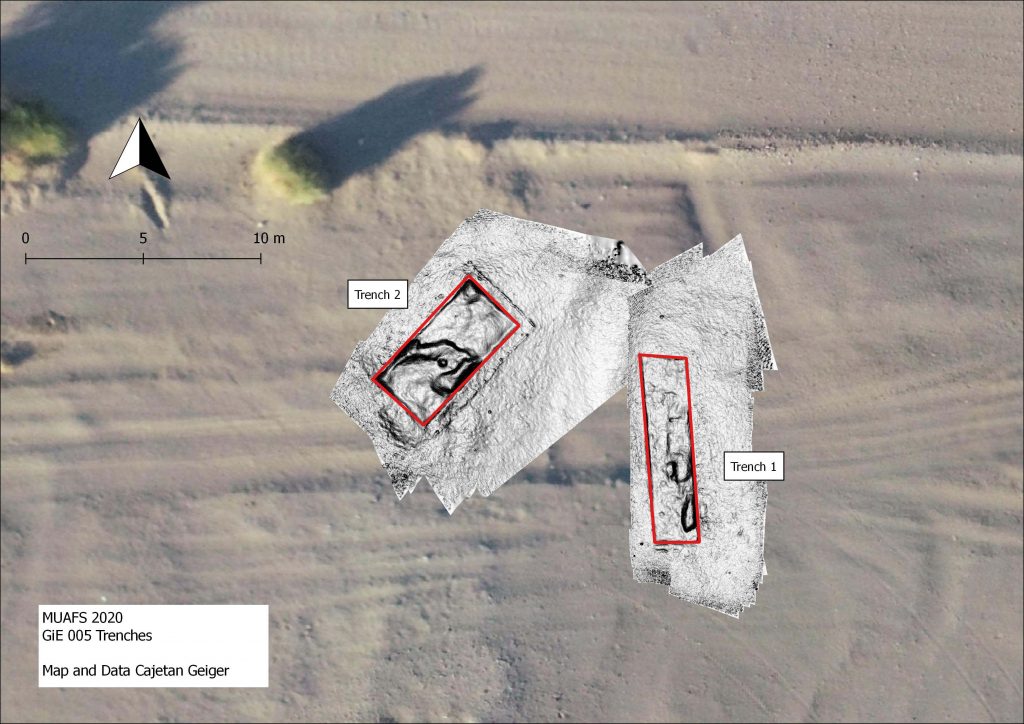

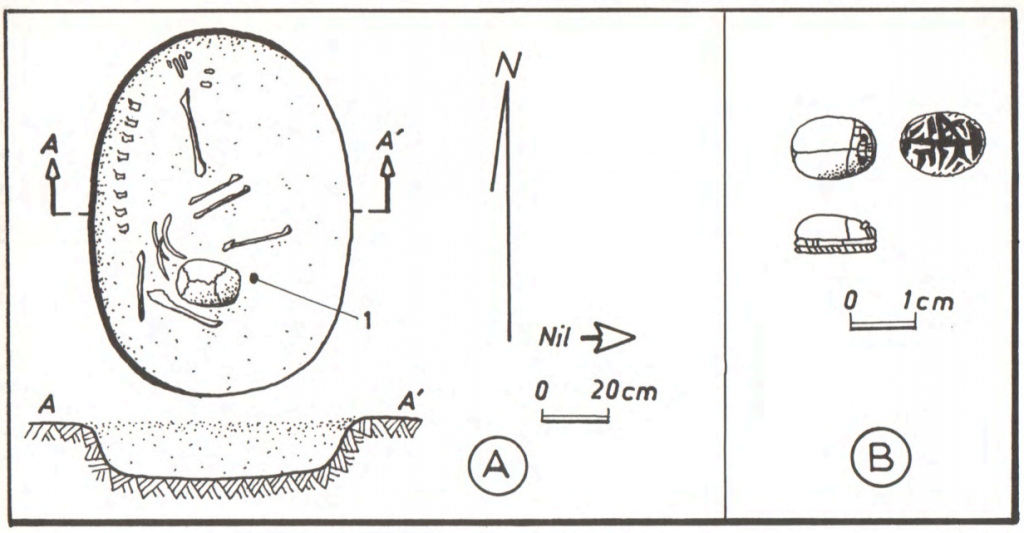

The region from Attab to Ferka was not only a contact space within the Kerma state. It was also an area where the Kerma ‘culture’ interacted with Egyptian patterns. For example, one very interesting burial was excavated by Vila at Shagun Dukki, Ginis East, where c. 10 other tombs were detected (figure 2). It consisted of a shallow, oval pit inside of which a flexed skeleton was found (disturbed). Together with the skeleton, a bone scarab was found in the right hand, a common pattern at Classic Kerma burials at Kerma city (Minor 2012: 144). Most scarabs found at Kerma city bear similarities with scarabs from Second Intermediate Period Egypt and Syria-Palestine and would have been acquired either via trade or reuse of graves in Lower Nubia (Minor 2012: 138-140). It is difficult to read the signs on the base of the scarab from Shagun Dukki. Moreover, bone was a material used to manufacture various items in the Kerma Period, as well as among other Nubian communities, and worked as a Nubian identity marker in the New Kingdom. Were bone scarabs the result of local copying practices? Looking at the evidence from Attab-Ferka holds the potential to shed light on internal contact and variability within the Kerma realm, as well as the local roles of foreign objects in local contexts in this period.

Gratien has previously pointed out how little we know about the Kerma state outside Kerma city, as well as how the Kerma state related to other ‘Nubian’ communities north and south of the Third Cataract (Gratien 2014: 95; 1978; Bonnet 2014). Evidence from Sai (Gratien 1986) and the Fourth Cataract (Paner 2014; Herbst and Smith 2014; Wlodarska 2014; Emberling et al. 2014) can illuminate further aspects of the spread of Kerma throughout the Middle Nile. The publication of evidence from Lower Nubia is also much expected (see Edwards 2020). Recent scholarship has also been shedding light on alternative, ‘rural’ experiences of the Kerma state outside of Kerma city (Akmenkalns 2018) and comparative, ‘global’ perspectives on specific categories of artefacts across cultural borders provide interesting avenues of inquiry (Walsh 2020). In a few years, the results of the DiverseNile Project will also contribute to our understanding of a more complex and diversified landscape beyond rigid cultural divisions.

References

Akmenkalns, J. 2018. Cultural continuity and change in the wake of ancient Nubian-Egyptian interactions. PhD thesis, University of California Santa Barbara.

Bonnet, C. 2014. Forty years research on Kerma cultures. In The Fourth Cataract and beyond, eds. J. Anderson and D. Welsby, 81-94. Leuven: Peeters.

Budka, J. 2020. Kerma presence at Ginis East: The 2020 season of the Munich University Attab to Ferka Survey Project. Sudan & Nubia 24: 57-71.

Edwards, D. ed. 2020. The Archaeological Survey of Sudanese Nubia, 1963-69. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Emberling, G. et al. 2014. Peripheral vision: Identity at the margins of the early Kingdom of Kush. In The Fourth Cataract and beyond, eds. J. Anderson and D. Welsby, 329-336. Leuven: Peeters.

Gratien, B 1986. Saï I. La Nécropole Kerma. Paris: CNRS.

Gratien, B. 1978. Les cultures Kerma: essai de classification. Villeneuve-d’Ascq: Publications de l’Université de Lille III.

Gratien, B. 2014. Kerma north of the Third Cataract. In The Fourth Cataract and beyond, eds. J. Anderson and D. Welsby, 95-101. Leuven: Peeters.

Herbst, G. and S. T. Smith. 2014. Pre-Kerma transition at the Nile Fourth Cataract: First assessments of a multi-component, stratified prehistoric settlement in the UCSB/ASU Salvage Concession. In The Fourth Cataract and beyond, eds. J. Anderson and D. Welsby, 311-320. Leuven: Peeters.

Minor, E. 2012. The Use of Egyptian and Egyptianizing Material Culture in Nubian Burials of the Classic Kerma Period. PhD thesis, University of California Berkeley.

Paner, H. 2014. Kerma Culture in the Fourth Cataract of the Nile. In The Fourth Cataract and beyond, eds. J. Anderson and D. Welsby, 53-80. Leuven: Peeters.

Vila, A. 1977. La prospection archeologique de la valee du Nil au sud de la cataracte de Dal 5. Paris: CNRS.

Walsh, C. 2020. Techniques for Egyptian eyes: Diplomacy and the transmission of cosmetic practices between Egypt and Kerma. Journal of Egyptian History 13: 295-332.

Wlodarska, M. 2014. Kerma burials in the Fourth Cataract region – Three seasons of excavations at Shemkhiya. In The Fourth Cataract and beyond, eds. J. Anderson and D. Welsby, 321-328. Leuven: Peeters.