For an Africanist archaeologist working in North Africa, the fall and winter seasons are mostly dedicated to excavation, while spring marks some how the beginning of the “conference season”.

Here, as a follow up of the blog post written by my colleague Chloë Ward on the Sudan Studies Conference Naples, I am glad to shorty report on the 16th EMAC Conference I attended last week in Pisa, Italy.

The EMAC is a important biennial conference gathering scholars and researchers with a broad spectrum background on ceramic technological and provenance studies from both the humanistic and hard science disciplinary areas. New approaches and up-to-date laboratory techniques to the study of ancient ceramics are typically presented in terms of analytical procedures, methodological papers, and case studies from all around the world.

The 1st EMAC edition took place in Rome, in 1991, while the first EMAC I personally attended was in Vienna, in 2011. This year, after two years of postponement because of the Covid Pandemic, the 16th edition of the EMAC has been back as an in-person conference in Italy, held by the University of Pisa, in the splendid setting of its Medieval and Renaissance town which is also one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Europe. Further, this year the EMAC conference was preceded by a 1st edition of the EMAC School dedicated to PhD students and young researchers as an opportunity for advanced training in non-destructive and non-invasive methods for the study of archaeological ceramics.

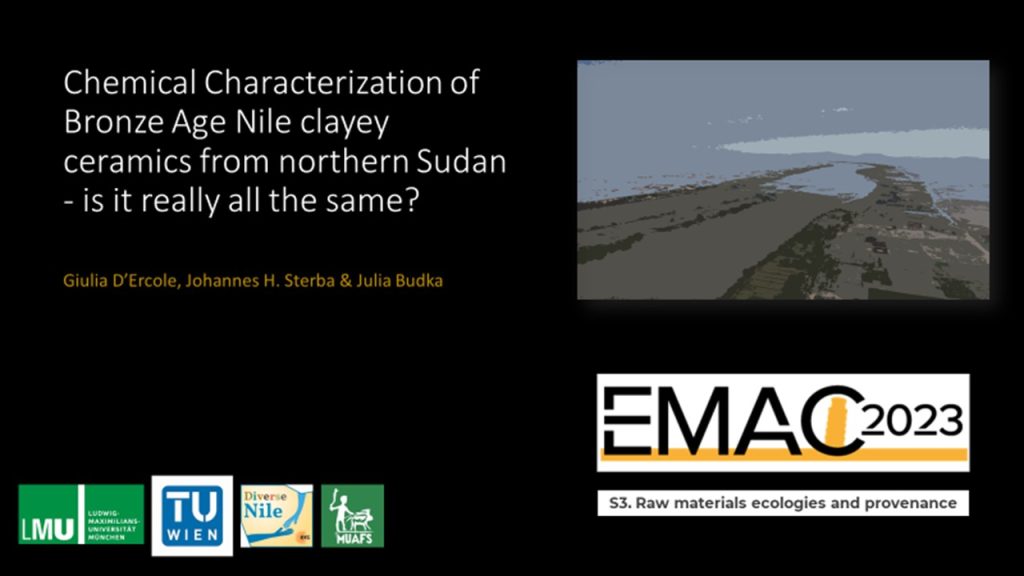

The conference (June 14-16) consists of six scientific sessions covering the diverse topics of Digital archaeology and potteries studies (S1), Experimental archaeology, technological traces, use wear and organic residues (S2 + S4), Raw materials ecologies and provenance (S3), Technology and production (S5), and Theory and Methods (S6).

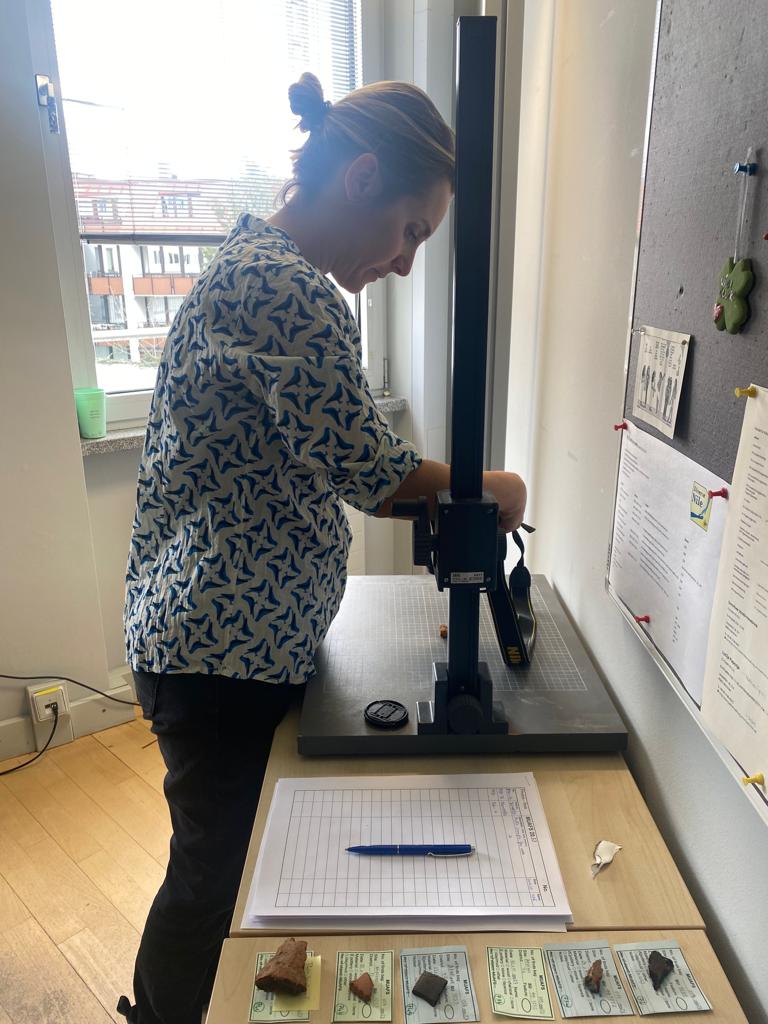

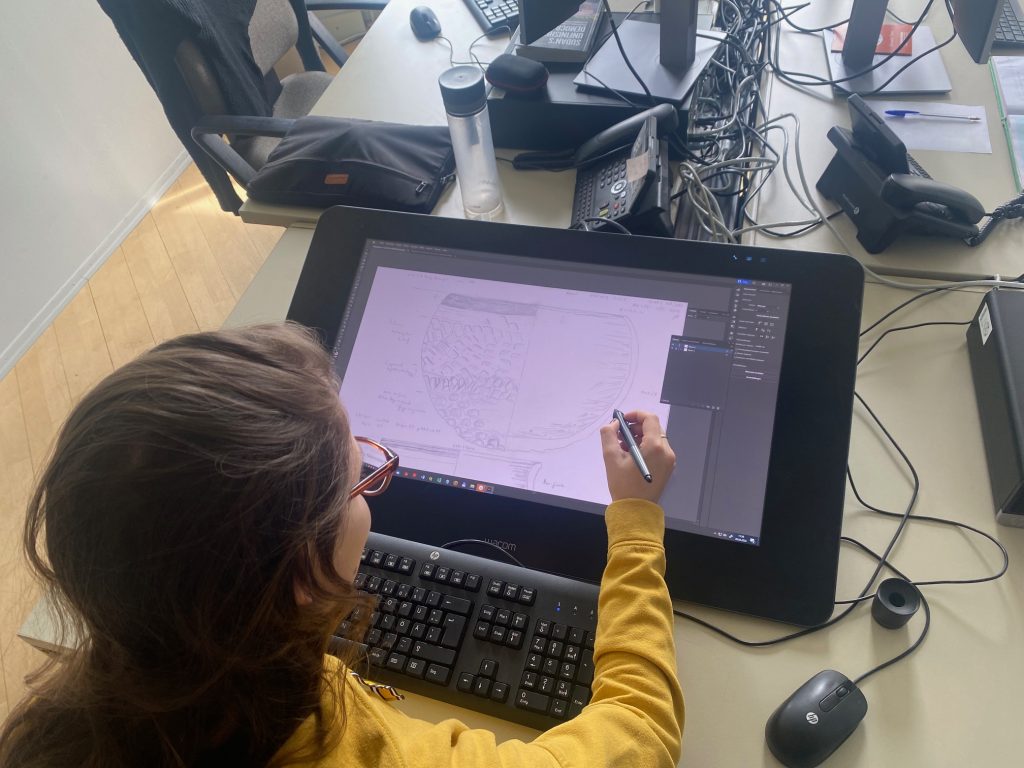

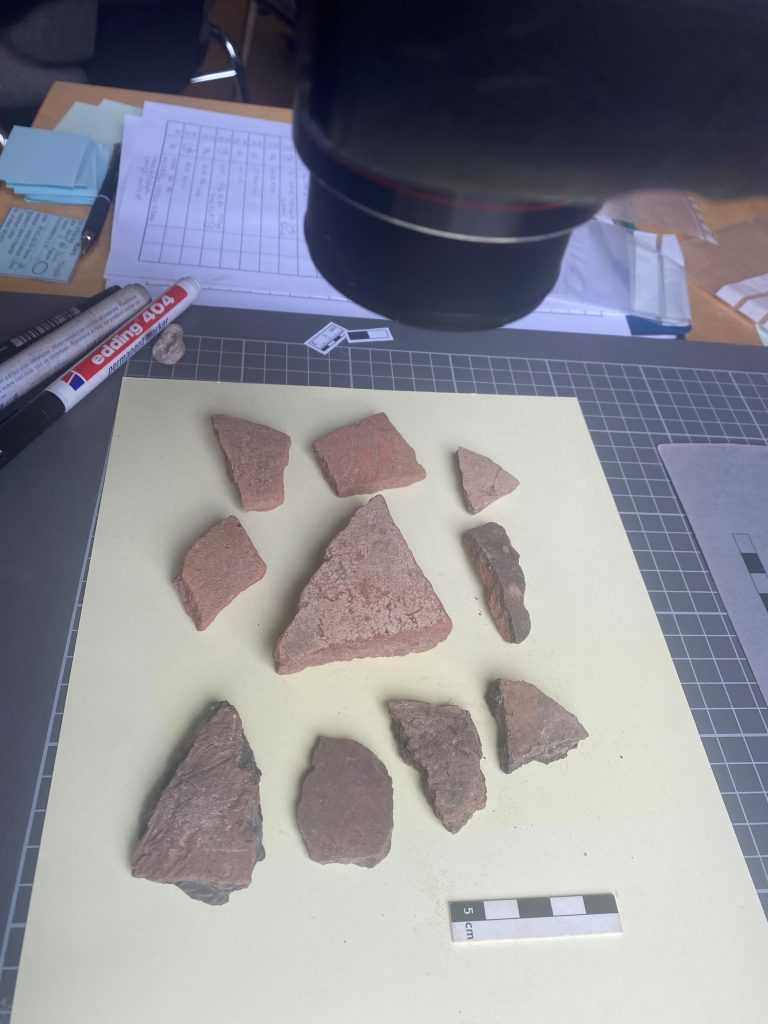

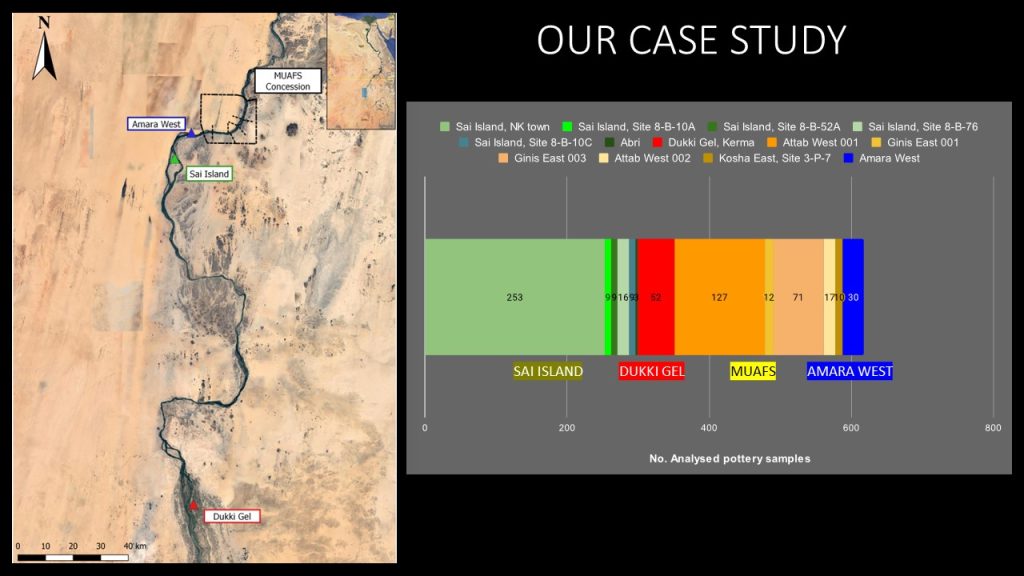

Our paper titled Chemical Characterization of Bronze Age Nile clayey ceramics from northern Sudan – is it really all the same?, co-authored by our PI, Julia Budka, Johannes H. Sterba, our colleague from the AI in Vienna, and by myself was included in Session 3: Raw materials ecologies an provenance. All in all, it summarized our study on over 600 ceramic samples conducted in the last 10 years within the framework of Julia’s ERC projects AcrossBorders and DiverseNile, dealing with the challenging but otherwise successful application of bulk geochemical analysis (Neutron Activation Analysis or NAA) to establish provenance for these characteristic vessels manufactured in Nile clay.

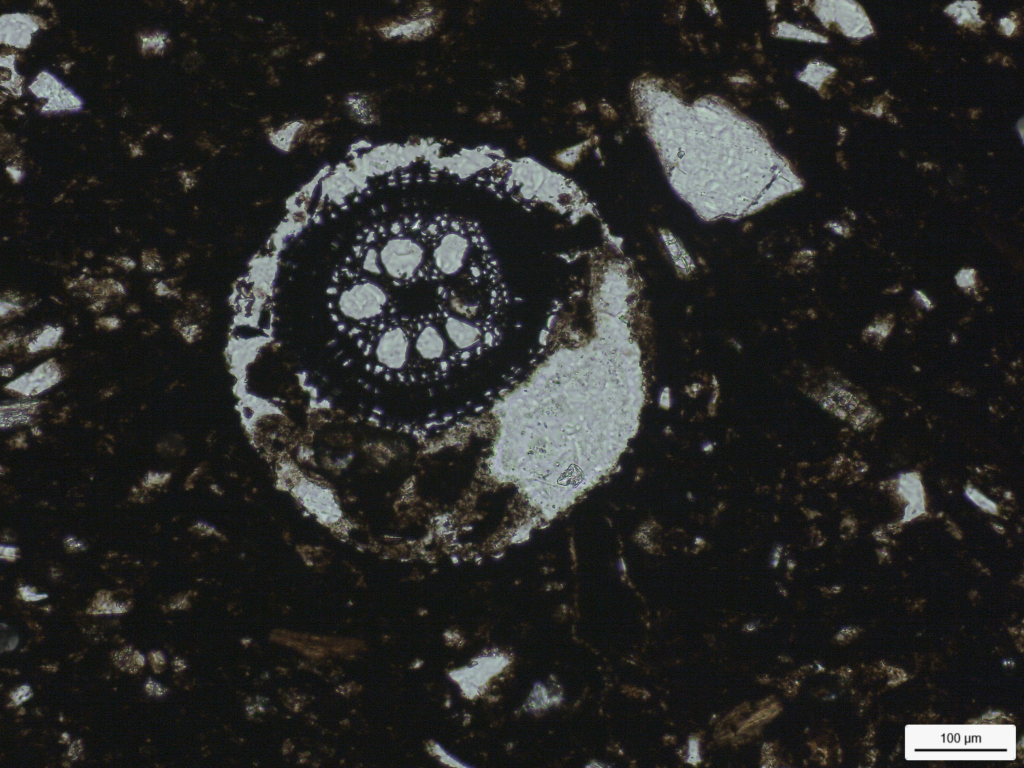

Specifically, our case study spans several millennia from prehistory to the Late Bronze Age (New Kingdom period) and comprises ceramic material collected over a long stretch of the Nile, including our last samples from the new sites excavated in the MUAFS concession area, the AcrossBorders ceramic samples from the temple town of Sai Island, and further reference material among which the beautiful potsherds from the site of Dukki Gel, Kerma. Within this large data set, we aimed to investigate minute changes in the chemical composition of Nile clayey ceramics that might help to differentiate their provenance and production technology. In detail, we looked for bulk compositional differences (or otherwise similarities) between different traditions (i.e., wheel-made Egyptian style and hand-made Nubian style pottery), chronological periods, and sites/locations. We focused our interpretation on the preparation of the clay, that is the particular recipe or formula adopted by the ancient potters to produce their vessels. We recognized in fact that considering just the clay raw material is possibly not sufficiently representative of the whole range of cultural and social drives as well as of performative actions (e.g., depuration of the clay, tempering and so on) carried out at the anthropic level to make a given paste particularly suitable for the production of a certain type of traditional vessel.

I am pleased to remark here that our talk was appreciated not only as a specific case study but more in general for the questions and challenges it proposed at the interpretative level, as a methodological paper.

Further, I really valued the holistic vision of the conference and the successful attempt of the organizing board to well intertwine over the different sessions the many different subjects and issues on ceramic production and use, such as to ideally follow all the successive stages of the manufacturing sequence, from raw material procurement to preparation, production, use and finally discard of the vessel. Further, this 16th EMAC gave more space to experimental archaeology, ethnographic study, and finally first tried to incorporate ORA studies in the wide range of inorganic analyses on ancient ceramics.

Of particular interest for us was certainly the talk given by Maritan et al. on the local and imported ceramic material from the Meroitic site of Sedeinga, nearby Sai Island, but I also much appreciated the methodological communication by Hein, Buxeda, Garrigós and Kilikoglou on the “Representativeness of a ceramic assemblage – significance and confidence in relation to sample size”, and the many good papers on the issue of manufacturing and shaping techniques, among which that by Gait et al. which nicely introduced the application of non destructive small-angle neutron scattering analysis (SANS) to identify forming techniques for both wheel made and handmade pots.

To conclude, I deeply admired the eco-friendly and low environmental impact slant of this 16th EMAC edition with its delicious and fully vegetarian Italian buffet, organic wine tasting, non-printed program and abstract book, and mostly the EMAC 2023 committee decision to donate the funds to charitable initiatives for the planet and the communities that inhabit it.