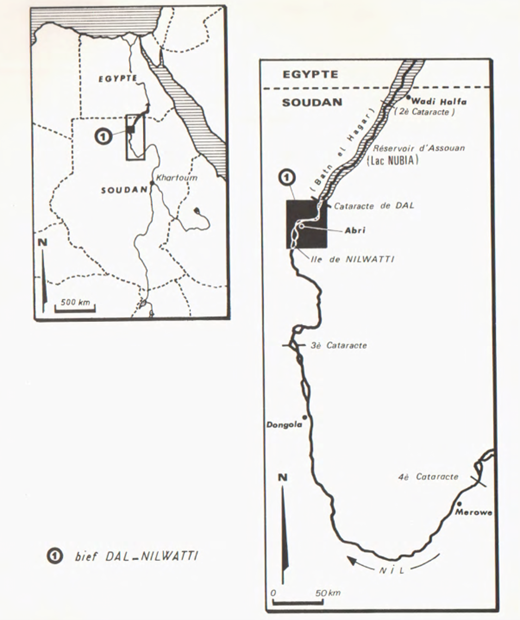

Since joining the project in June, I have been busy catching up on the research that has been conducted to date. A considerable amount of this goes back much further than the start of the DiverseNile project to an archaeological survey which took place between 1969 and 1973 directed by André Vila (Budka 2020). As much as we archaeologists enjoy excavation, we also spend a huge amount of time using and building on the work of our predecessors (see also the earlier blog posts by Rennan Lemos and Veronica Hinterhuber). This is particularly important when considering large concession areas such as the one held by the DiverseNile project and the questions the project poses.

Past work such as Vila’s survey can help inform current (and future!) projects in myriad ways. At the most basic level, we can use the results to help locate potential sites of interest for the project and then identify and re-explore them in the field in Sudan. This can also be significant in noting changes in archaeological sites since Vila’s survey, which is crucial for their preservation (Budka 2019; 2020). We can also integrate past data into our current research, increasing the data we have available at our disposal to answer our present research questions. Finally, we can use this survey data to explore research and archaeological practices both today and in the past. Understanding these practices is crucial as they directly influence the way that archaeological knowledge is constructed (Ward 2022). Therefore, a key consideration when using Vila’s data is to understand how it was collected and presented at the time, this means we can make use of it much more effectively. To this end, considering Vila’s results as ‘legacy data’ is a useful way of integrating this past research into our current project.

Normally, the term legacy data in archaeology is used to define ‘obsolete’ archaeological data but, given the vast importance of digital data for any kind of analysis, manipulation, or mapping, this can broadly be applied to any data which is not digital (Allison 2008). As such, any work involving the re-contextualisation, application of modern techniques, or modelling of past data can be considered working with legacy data (Wylie 2016). Thinking of this evidence as legacy data rather than simply data is crucial when using it in any new or future research as it demands a more complex engagement with the material then simply extracting quantitative data. It would be redundant to simply apply new methods to old data, without engaging with more fundamental questions which consider how the data was originally collected and how it fits into the broader historical and methodological contexts of previous studies.

Fortunately for us, Vila’s survey is comprehensively published across 11 volumes, all of which are available on the website of the SFDAS (Section française de la direction des antiquités du Soudan). The volumes are nicely bookended by an introductory volume — which provides crucial information on how the survey and recording was conducted by the team, as well as the classification system used — and a concluding volume — which provides some quantitative analyses of the results of the survey.

This is a fantastic resource for the project to draw upon as a key consideration when making effective use of legacy data is not only to understand the methodological processes used, but also to ensure the replication of past results (Corti and Thompson 2004; Corti 2007; Corti 2011). As in any science, the reproducibility of results is fundamental in ensuring the accuracy — and therefore usability — of past research, which is crucial when incorporating it into contemporary research. Furthermore, advances in the archaeology of Sudan means that some of Vila’s results — for example, in terms of phasing — may well need to be re-examined and ‘updated’ to take into account the half-century of subsequent research.

Of course, all of this leads to additional questions on the future of the research and data created by the DiverseNile project. This includes thinking about the best ways to collect, store, and share our data and ‘futureproof’ our work.

Keep reading the blog for future updates on Vila’s work and its integration into the DiverseNile project!

References

Allison, P. 2008. Dealing with Legacy Data ‒ an introduction. Internet Archaeology 24. DOI:10.11141/ia.24.8

Budka, J. 2019 (with contributions by Giulia D’Ercole, Cajetan Geiger, Veronica Hinterhuber & Marion Scheiblecker). Towards Middle Nile Biographies: The Munich University Attab to Ferka Survey Project 2018/2019, Sudan & Nubia 23:13‒26

Budka, J. 2020. Kerma presence at Ginis East: the 2020 season of the Munich University Attab to Ferka Survey Project, Sudan & Nubia 24: 57‒71

Corti, L. 2007. Re-using archived qualitative data ‒ where, how, why? Archival Science: 37‒54

Corti, L. 2011. The European Landscape of Qualitative Social Research Archives: Methodological and Practical Issues. Forum: Qualitative Soical Research 12(3)

Corti, L. and Thompson, P. 2004. Secondary Analysis of Archive Data. In: Seale, Gobo, Gubrium, et al. (eds) Qualitative Research Practice. London: Sage: 327‒343

Vila, A. 1975. La prospection archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise). Fascicule 1: General introduction. Paris: CNRS

Vila, A. 1979. La prospection archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise). Fascicule 11: Récapitulations et conclusions. Paris: CNRS

Ward, C. 2022. Excavating the Archive/Archiving the Excavation: Archival Processes and Contexts in Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Practice 10(2). DOI:10.1017/aap.2022.1

Wylie, A. 2016. How Archaeological Evidence Bites Back: Strategies for Putting Old Data to Work in New Ways. Science, Technology, & Human Values 42(2): 203‒225