The most recent publication of the ERC DiverseNile Project focuses on landscape and resource management in Bronze Age Nubia. Here, I would like to present some thoughts on the regionality of stone quarrying in Nubia with a case study from the MUAFS concession.

Stone is a natural resource which has typically been associated with Egypt, being regarded as a raw material of little importance for Nubian cultures. However, the quarrying of stone played a role in the complex framework of cultural exchange of Middle Nile communities with Egypt (see Budka 2024). Whereas Nubian sandstone (quartz sandstone) only started to be used as building material in the Middle Nile during the Middle Kingdom, mostly for Egyptian fortresses, there is evidence for a much earlier use of natural- and dry-stone architecture, in both settlement architecture and funerary buildings (cf. Liszka 2017). Sandstone architectural pieces were also well integrated within Nubian monumental architecture (e.g., the columns and stelae at the eastern Deffufa in Kerma, see Budka 2024 with references). Some of the most important sandstone quarries during the New Kingdom can be found at Sai Island – we have studies these quarries already during the ERC AcrossBorders Project and will come back to the topic within the framework of our present project in the near future thanks to the expertise of our PostDoc Fabian Dellefant.

Granite is another important stone quarried in Nubia. While the most renowned granite quarry used for building projects and objects in ancient Egypt over millennia is located in Aswan, there are also a number of granite quarry sites in the Middle Nile. They are less well known and seem to have been used for a considerably shorter amount of time.

One quite famous example is the site of Tombos close to the Third Nile Cataract. The site includes a large quarry of magmatic rocks, principally granite and granitic gneisses, with known activity from the 18th Dynasty until Napatan and Meroitic times, particularly for statues and stelae. One particularly striking left-over in the quarry is the beautiful, although unfinished royal statue of presumably Napatan date.

There is no clear evidence that the quarry site of Tombos was used prior to the New Kingdom (Klemm, Klemm and Murr 2019, 28).

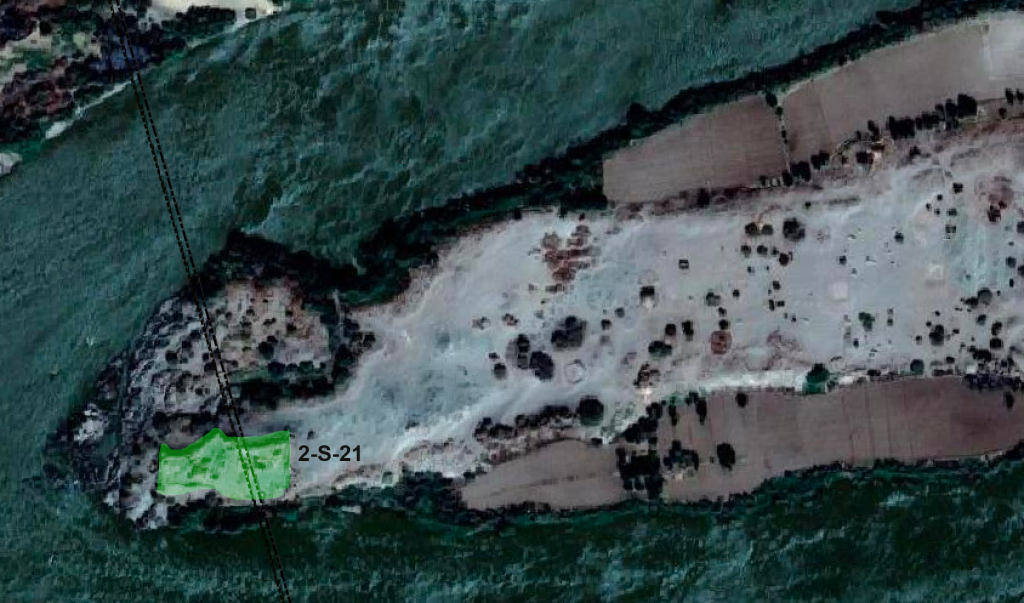

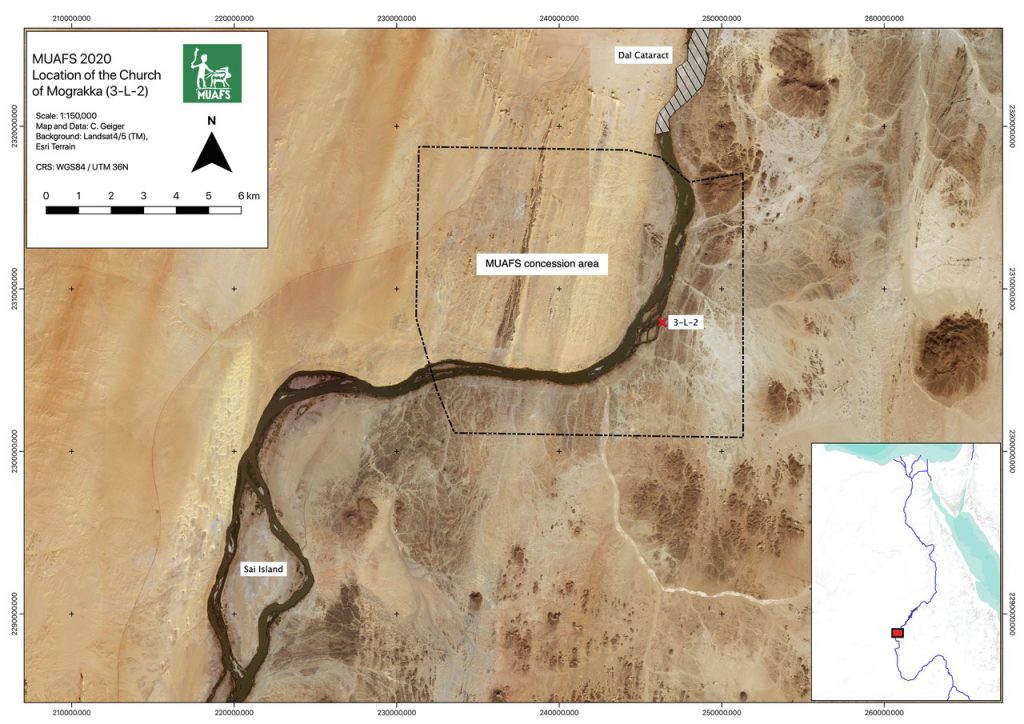

Another type of granite, pink granite, is available just south of the Dal Cataract in the MUAFS concession. This brings me to my case study: site 3-L-6 is a large red granite quarry at the foot of Jebel Kitfoggo in Ferka West – well noted by Vila and others during the 1970s survey (Vila 1976, 72−73). We visited the site during our 2022 survey of the MUAFS project – the landscape is fantastic and the pink granite very picturesque.

Fragments of unfinished columns in the southern part of the site testify to an intensive use in Medieval times for architectural pieces (Welsby 2002, 173).

This is supported by evidence from settlement site 3-G-30, just to the north of 3-L-6, where Medieval ceramics were found on the surface. The building technique and general layout of these stone-built huts are also typical of the Medieval era.

Although several Kerma sites are also identifiable in the surroundings of 3-L-6, there is no evidence for Bronze Age or Iron Age use of the granite quarry at Jebel Kitfoggo.

It is interesting to stress that both Tombos and Jebel Kitfoggo were used for a relatively limited time span compared to other quarry sites. These examples illustrate regional patterns in quarrying in the Middle Nile, but they also show the need to consider political and historical circumstances when investigating the management of raw material and resources (Budka 2024).

References

Budka 2024 = J. Budka, Introduction. Regionality of resource management in Bronze Age Sudan: an overview and case studies, in: J. Budka and R. Lemos (eds), Landscape and resource management in Bronze Age Nubia: Archaeological perspectives on the exploitation of natural resources and the circulation of commodities in the Middle Nile, Contributions to the Archaeology of Egypt, Nubia and the Levant 17, Wiesbaden 2024, 19−33.

Klemm, Klemm and Murr 2019 = Klemm, D., Klemm, R. and Murr, A., Geologically induced raw materials stimulating the development of Nubian culture, in: D. Raue (ed.), Handbook of Ancient Nubia, Vol. 1, Berlin; Boston 2019, 15−38.

Liszka 2017 = Liszka, K., Egyptian or Nubian? Dry-stone architecture at Wadi el-Hudi, Wadi es-Sebua, and the Eastern Desert, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 103 (1) (2017), 35−51.

Vila 1976 = Vila, A., La prospection archéologique de la Vallée du Nil, au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Soudanaise). Fascicule 3: District de Ferka (Est et Ouest),Paris 1976.

Welsby 2002 = Welsby, D.A., The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia: Pagans, Christians and Muslims Along the Middle Nile, London 2002.