Less than two years after the 16th-edition-of-the-european-meeting-on-ancient-ceramics-emac I had the pleasure of returning to the splendid setting of Pisa to attend the International Conference Embedded in Clay – Identity and Performance in Figurines and Ceramic Objects from Ancient Societies, organized by prof. Gianluca Miniaci and the team of the pipe-project at the Dipartimento di Civilta’ e Forme del Sapere, University of Pisa (Italy).

Upon receiving the kind invitation from Beatriz Noria-Serrano, Georgia Long, and Hannah Page, the three project postdocs and primary organizers of this event, I was pleasantly surprised by their intention to revive the topic of clay figurines − every so often neglected or kidnaped by ceramicists (Gianluca Miniaci cit.) – and situate this within a novel and much more comprehensive framework, to foster a collaborative environment amongst scholars whose methodologies pertain to the analysis of identity and performance as manifested in clay artifacts. The final result exceeded expectations!

In a friendly and informal setting, with an agenda (for details see, embedded-in-clay-conference-programme) covering a wide range of chronologies and geographies, from the Ancient Nile Valley in Egypt, through northern and central Sudan, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Asia, and with an equally well-calibrated assortment of lectures and roundtables to stimulate discussion among the various specialists, the three conference days flew by, and it seems only yesterday that we were all enchanted by Richard Lesure’s (University of California, LA) exciting keynote on figure-making during the Formative era in Mesoamerica.

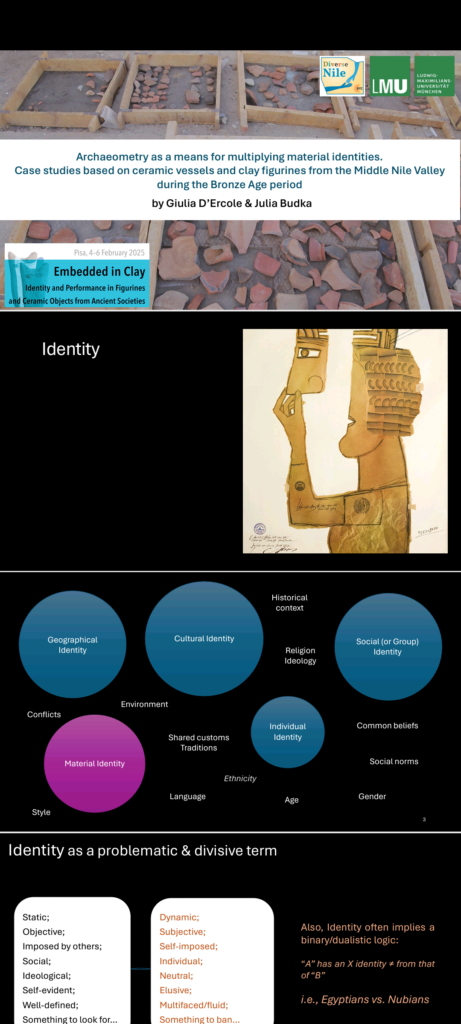

In this schedule, our paper entitled ‚Archaeometry as a means of multiplying material identities. Case studies based on ceramic vessels and clay figurines from the Middle Nile Valley during the Bronze Age‘ opened the second day of the conference, which was entirely dedicated to the concepts of identity and performance through the lens of archaeometry, while the last day was devoted to archaeology.

The talk has been formally divided into three macro-parts, starting with a theoretical introduction on the subject of identity in archaeology, and continuing with case studies, the first on clay figurines from the site of Sai Island, while the second dedicated to the analysis of the ceramic corpus from the neighbouring region of Attab and Ferka, in the hinterland of Sai and Amara West. Overall, we have tried to present some preliminary results, based on the different laboratory methodologies (INAA; OM; Raman Spectroscopy, XRD; Micro-CT; SANS) we have applied in the framework of the Diverse Nile project, dealing with a very large data set of samples from different sites. Most importantly, we have tried to emphasize how, over the years and thanks to the impact of postcolonial archaeology, our approach through materialities has significantly shifted − we do not work anymore along dichotomies and schematizations of identities (e.g. Egyptian vs. Nubian manufacturers). Instead, we explore open questions that also imply the complexity, hybridity, and entanglement of multiple material (and thus cultural) identities.

As the conference progressed, some of our questions were considered, debated, and answered in subsequent talks, while others perhaps emerged and stimulated my new thinking.

During the round table that wrapped up the conference, I took note of many themes and new and much-needed research perspectives on the subject of clay figurines that we agreed on: the need to revise the terminology, which is often too schematically limited to the distinction between human and zoomorphic figures; to take greater account not only of the function and performance of figurines, but also of their re-use and possible multifunctionality, both in synchronic and diachronic terms; to look at chaîne opératoires and gestures and fingerprints and, through them, reconstruct novel and hidden narratives related to women and children; eventually go beyond the surface and the ‘outer skin’ of the figurines, beyond traditional typologies and performances, in search of new ontologies and dynamic meanings.

The liveliness of that discussion, with so many pleasant colleagues and friends, still resonates in my mind, blending the gentle landscape of Pisa with the lights of the sunset on the Arno, another river, like the Nile, which has been crossed every day for ages by boats, and items, and by the glances and encounters of many diverse people.