Digital technologies continue to inundate archaeology as a means of bridging scientific and humanistic approaches. More than merely an exercise in playing with flashy machines and fancy toys, 3D printing has wide-ranging implications for fostering education and outreach, the accessibility of archaeological heritage, and explorations in experimental archaeology.

In my first month as a postdoc with the DiverseNile project, I began looking into different strategies and methodologies for making 3D models and prints of small objects. First up, we looked into printing a seal impression from the AcrossBorders project’s excavations at Sai Island. This mid-18th dynasty mud seal impression bears the name of Nehi and the title “Overseer of the Gateway” and is intact apart from a finger smudge in the lower left corner.

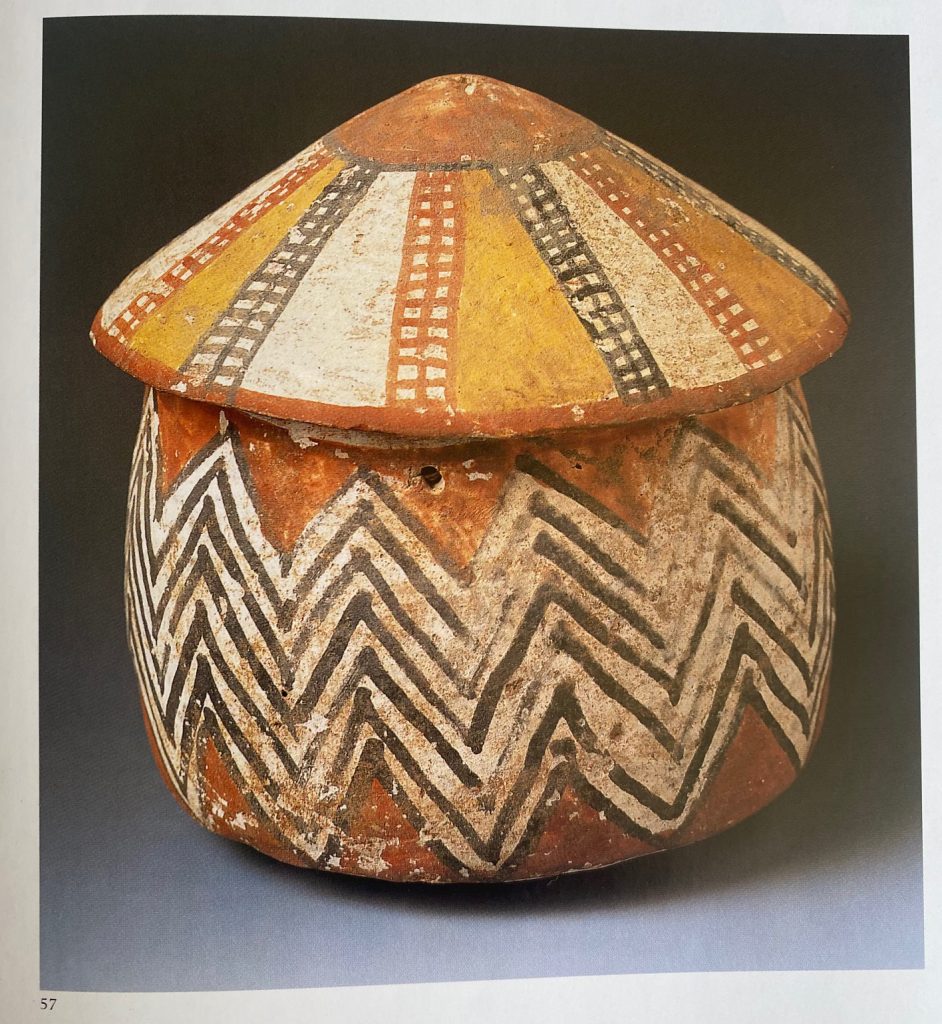

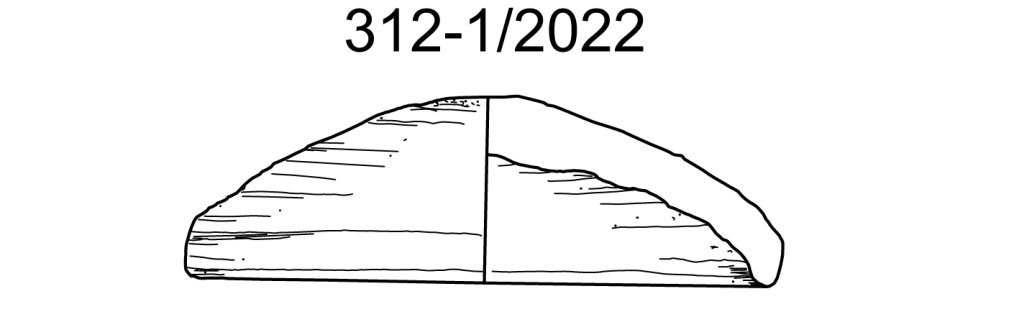

We also decided to experiment with printing an inscribed stone heart scarab also from the AcrossBorders project at Sai Island (figure 1). This object was excavated from the 18th dynasty burial of Khnum-mes and is inscribed on the bottom with Chapter 30 from the Book of the Dead (Budka 2021). Check out a blog post from 2017 about this find here.

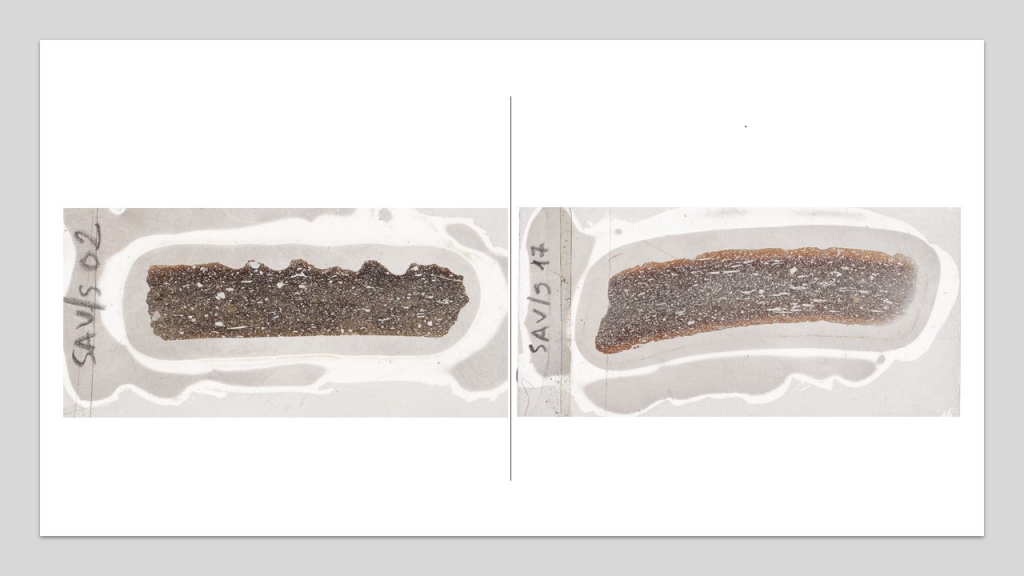

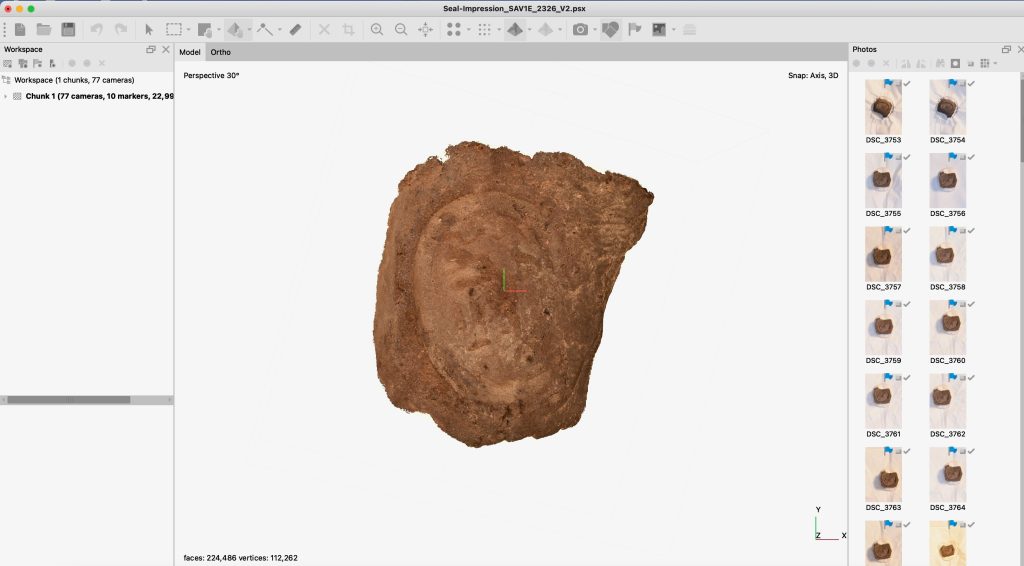

To create models, we use photogrammetric methods to align photos of the object in Agisoft’s Metashape to create a textured mesh (figure 2). The photos of this object were taken during a study season in Khartoum in 2017 by Cajetan Geiger.

For this project, we needed a printed object quickly for a television appearance (keep reading to find out more!) so I looked into commercial printing options. I came across Xometry, a Germany-based company offering on-demand manufacturing of industrial parts. I like to think that they were both confused and delighted when they saw the small, inscribed objects on their platform!

Pros of this service: Xometry has a well-designed, functional, and easy to use website. With their instant quoting engine, you can upload 3D models (.stl, .obj, and many other formats) and immediately receive a cost and shopping estimate. Also, if there are issues with your model the engine will detect them. You can also choose the specific color, material, weight, and finish of your print.

Cons: While the website has extensive options for types of printing materials, most of the options are obviously very light-weight industrial plastics, polycarbonates, silica glasses, and nylons. If you are aiming for realism in your 3D print, you will not come across colors or materials on this site that can replicate those of many archaeological objects. Also, it should be noted that for this company, the minimum order is €50. If you just want one or two prototypes of small objects, you will have to order A LOT of copies just to come close to this high of a minimum!

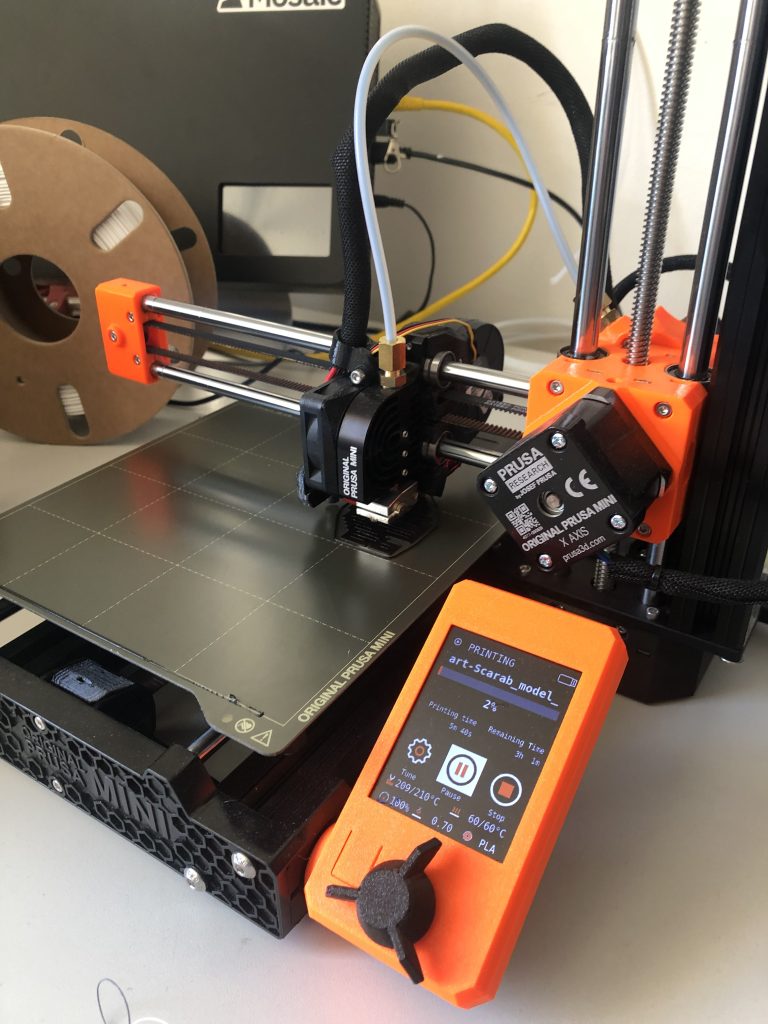

Given the drawbacks of working with large 3D printing companies like Xometry, I began to look into the possibility of collaborating with institutes on campus that may offer printers. After a bit of digging, I contacted the Medieninformatik Lab at LMU. Luckily, they have, not one, not two, but three (!) high quality, professional 3D printers; a Prusa Mini+ (PLA-3D printer), a Prusa i3 MK3S+ (PLA-3D printer), and the pièce de resistance, a Formlabs Form 3 (SLA-3D printer). The Prusa Mini+ and Prusa i3 models are some of the most ubiquitous printers (figure 3). They are extrusion-based printers which operate by heating a plastic material through a tube (filament) and distributing the heated material on a platform layer by layer, until it takes the full form of the object. The material is Polylactic acid (PLA) and can be heated at a low temperature. It is a robust, low-cost, and biodegradable material. Xometry prints using this method.

The Formlabs 3 printer operates with an entirely different method (figure 4). It uses stereolithography (SLA), which is a type of additive manufactory technology employing resin 3D printing. A light source like a laser or projector heats and cures liquid resin at a high temperature into hardened plastic in the shape of a 3D model. SLA printers have the ability to capture the highest resolution and most accurate details of objects, along with smoother surfaces and more complex geometries (size and shape of the print).

Preliminary Results Printing with Xometry and the Medieninformatik Lab:

As apparent in figure 5, three different printing methods yielded three vastly different results. On the far left of the image is a print of the seal impression using a Prusa Mini+. As is evident, the fine details of the inscription of Nehi were too high resolution for the printer to capture with accuracy. The inscription is not legible and overall, the surface and geometry of the object are not clean. The middle print is of the seal impression from Xometry. Even though Xometry used a PLA printer (like the Prusa) the print is of a higher resolution, and the geometry of the object is more accurate. The surface is smoother and the inscription, while not perfect, is legible. Lastly, the far-right print is from the Formlabs 3 printer. This by far, is the highest quality and highest resolution print! The inscription is very legible, and the geometry of the object is extremely accurate. The surface is also smooth, extremely detailed, and shows no signs of lumps or imperfections in the raw material. While the Formlabs 3 printer is a more time-intensive and expensive process, the cured resin clearly is the superior material to capture intricate and complex details of smaller objects (figure 6).

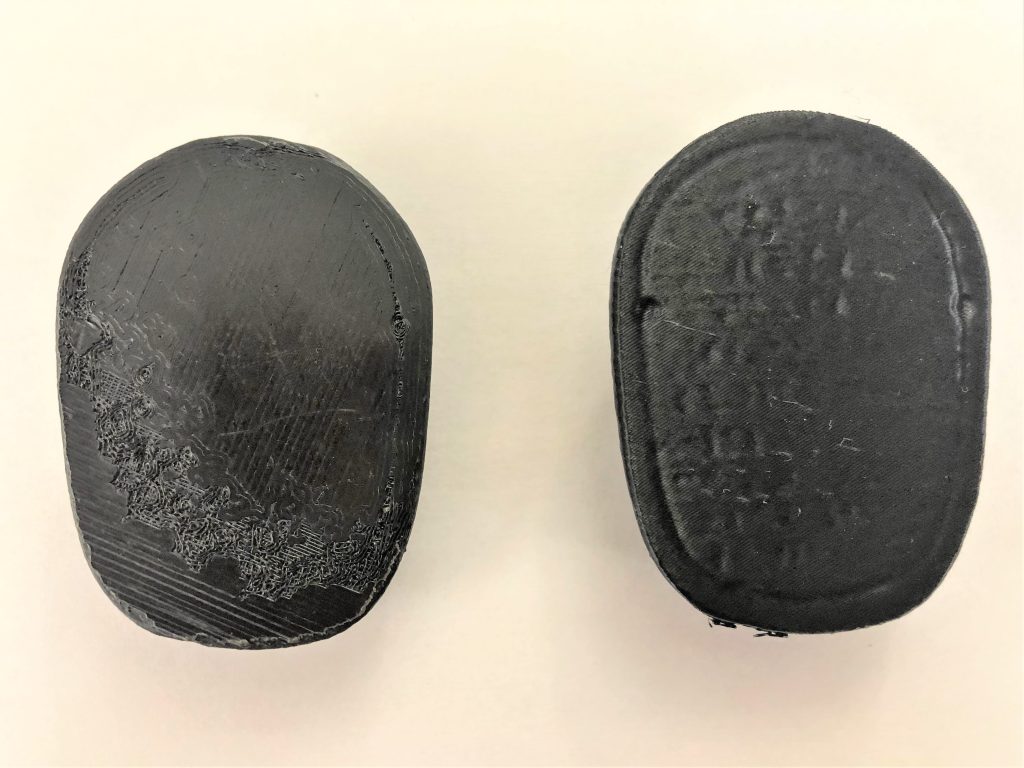

In terms of the heart scarab, the differences between prints are less stark but still significant. As evident in figure 7, the Xometry print (on the left) and the Prusa Mini+ print (on the right) are similar in shape and detail. The Prusa print has a smoother and cleaner surface, and slightly more legible details near the top of the scarab.

The bottom of the scarab demonstrates the biggest difference between the two prints (figure 8). The inscription was not captured at all on the Xometry print (left), due to the direction in which the print was oriented. If the print is rendered layer by layer with the bottom of the object flat on the printing platform, then any detail on the bottom of the object will not be captured. However, with the Prusa Mini+ print (right) the object was printed at an angle, and the result is a legible inscription (figure 9).

From these preliminary printing exercises, it was fascinating to see just how different prints of the same object can turn out given the variety of available printers, raw materials, and approaches. Clearly the various methods explored here have their pros and cons. 3D printing methods must be tailored to the specific goals of the project and qualities of the object/3D model. Trial and error, if you have the available resources and time, is a terrific way to start!

The Significance and Broader Impact of 3D Modeling and Printing

As an archaeologist who is interested in digital technologies, I am asked all the time (by fellow archaeologists and non-specialists alike), what is the purpose of making 3D models of artifacts that already exist? What keeps us from creating glorified toys that just sit and gather dust on shelves?

The truth is….3D modeling applications in archaeology is a means of addressing several unique problems of studying the ancient past. Firstly, 3D prints of archaeological objects that can be handled and shared without any risk of damage to the original artifact is invaluable. For objects that are restricted to museum collections or excavation archives, 3D models increase the accessibility of the archaeological record, not only to scholars in different regions, but also to members of the public. High quality 3D models that capture valuable information such as inscriptions and technological means of production can be used as tools in public outreach and education. In fact, our PI Julia Budka just demonstrated this during her recent appearance on the wildly popular children’s show, “1, 2, oder 3?” On a show dedicated to ancient Egypt, she brought our Xometry print of the seal impression to teach children that even objects made of seemingly quotidian materials like mud can be extremely important to archaeologists. 3D models expand and diversify the types of environments in which objects can be used in teaching.

Here is a link to the full episode if you would like to check it out!

Lastly, 3D printing can be used alongside other experimental archaeological approaches. For example, our graduate student Sofia Patrevita is studying goldsmithing techniques in Nubian jewelry making, including the lost wax technique. See her recent blog post here. The 3D printing lab at LMU has the ability to print objects in wax (among other materials), which could allow us to experiment with recreating jewelry in various stages of production, giving us insight into the chaîne opératoire of Nubian goldsmithing. Sofia and I are looking forward to exploring this possibility in future collaborations!

A huge thanks to the Medieninformatik Lab at LMU for access to their printers and resources, and especially to Boris Kegels for providing the access and printer training. Thanks also too Christine Mayer and Prof. Dr. Nicola Lercari of the Institute for Digital Cultural Heritage Studies at LMU for helping facilitate this collaboration!

Stay tuned for an update on our most ambitious 3D printing project yet, a to-scale reproduction of Khnum-mes’s shabti from Sai Island!

Reference:

Budka, Julia. 2021. Tomb 26 on Sai Island: a New Kingdom Elite Tomb and Its Relevance for Sai and Beyond. Leiden: Sidestone Press.