Before we’re able to go to the field, a lot of work on the cemeteries in our concession area is currently underway from Munich. Marion’s recent blog posts already discussed the potential of magnetometry for us to better understand what we are dealing with, and this is especially true in connection with Cajetan’s remote sensing work. Cajetan’s work has been revealing some interesting aspects of our sites and hopefully you’ll be able to catch glimpses of his work soon in here.

This work provides important background regarding the specificities of our sites. Alongside an assessment of the cemeteries and comparison with other sites across Nubia, this allows us to put together an ‚ideal type‘ (sensu Max Weber) that can guide us through future survey and excavation. The data sets produced by Vila, as well as previous MUAFS seasons, are also crucial for us to establish this ideal type, which works as a methodological tool to confirm our hypotheses (or not).

In my previous posts, I’ve already shared details about the assessment of sites I’ve been carrying out over the past months. Base on Vila’s data, we can know what to expect from the cemeteries in terms of preservation, types of structures etc. For example, the Late New Kingdom „tomb of Isis“ works an example of „elite“ or „sub-elite“ burial ground in the periphery of temple towns, where Egyptian and Nubian features mixed, probably to a greater extent than at temple towns—an example of hypothesis that we can create departing from an ideal type. This mixture occurred, for instance, in the combination of Egyptian substructures and a tumuli superstructure, remains of which were located in previous MUAFS seasons (see my previous posts). Departing from an ideal type such as the „tomb of Isis“ we can approach how the ideal varies across geographical and social spaces within our concession area.

For example, Marion and Cajetan’s work are shedding light on the extension of cemeteries where we can easily see from above those tumuli, some of which already explored by Vila, but also other features. It is difficult to determine from a distance what is the nature of this evidence. Comparative research then comes in handy. I’ve already proposed a discussion on the whereabouts of the majority of the Nubian population during the New Kingdom (a discussion that also applies to the Kerma period).

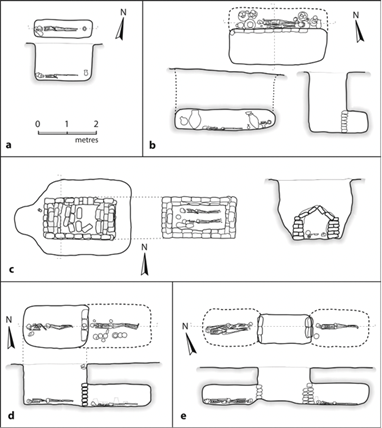

Other Nubian cemeteries such as Fadrus in Lower Nubia add information about non-elite groups to our ideal type (figure 1). If larger tumuli such as the „tomb of Isis“ are easily located based on drone and satellite imagery, simple non-elite pit graves originally with no extensive superstructures pose more challenges. Though, comparisons allow us to open up to possibilities that include, in our research framework, social groups not clearly represented by evidence accumulated from large temple-town cemeteries. These groups—which comprised the bulk of Nubian populations working in the fields, mines, and probably carrying out other work in the service of larger centres—are yet to be fully understood (and here work at the cemeteries of Amarna provide us interesting comparison points, see Stevens 2018).

Several are the challenges of doing research from the office, as we cannot yet go to the field. But work conducted so far, from various fronts, help us establish a pretty solid starting point from which to explore our sites knowing more or less what to expect. This takes into account old and new evidence, extensive comparisons with other sites and a clear theoretical framework, which is essential to formulate research questions and carry out large scale projects such as DiverseNile.

References

Säve-Söderbergh and Troy 1991. New Kingdom pharaonic sites: the finds and the sites.

Spence 2019. New Kingdom burials in Lower and Upper Nubia. In Handbook of Ancient Nubia, ed. D. Raue.

Stevens 2018. Death and the city: The cemeteries of Amarna in their urban context. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 28 (1): 103–126. doi:10.1017/S0959774317000592