We are pleased to announce that registration for the 16th International Conference for Nubian Studies (ICNS) in Munich, Germany, hosted by LMU Munich from 7th September to 12th September 2026, is now open.

We would like to thank everyone who submitted proposals for oral and poster presentations. We currently have more than 260 presentations scheduled alongside posters which will be displayed throughout the conference. Please be advised that the provisional programme, which is now available on the conference website, is still subject to change.

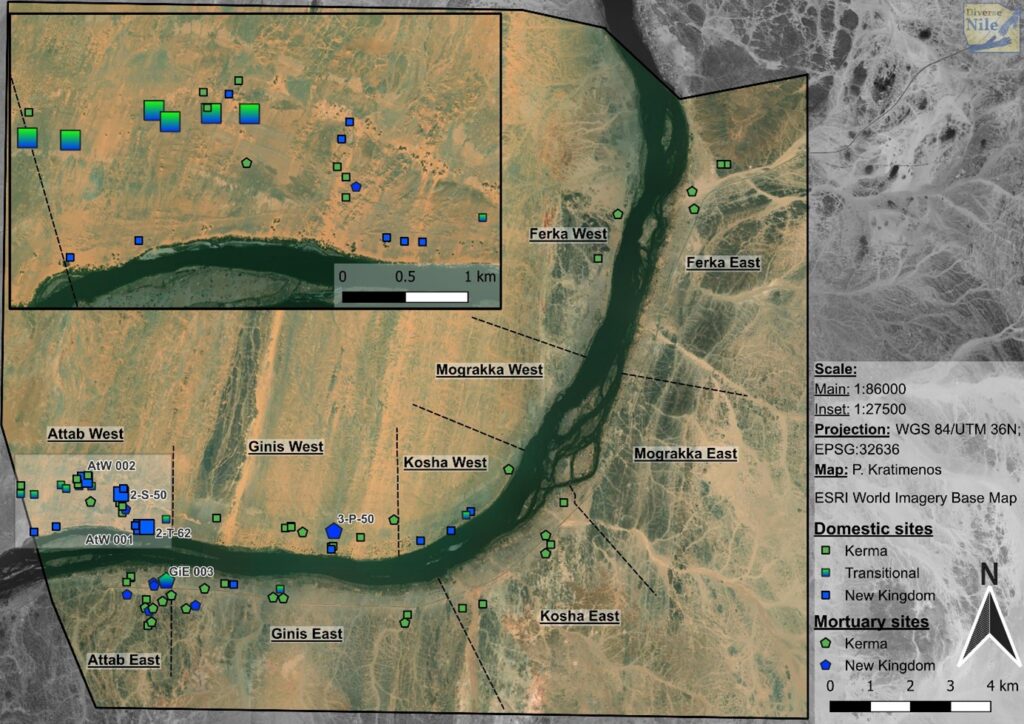

The main theme of the Munich conference, Multiple Nubias, is linked to the latest research findings of the ERC DiverseNile project. New research is starting to show that ancient Sudan was a lot more diverse than we thought, and that there were actually several different forms of Nubia. This goes against the common idea that Nubia was just one single place in the past. So, we’ve invited in particular sessions and papers to look at different experiences, regional traditions and individual actors – both human and non-human – over the millennia. There will also be four keynote speeches that will look at the main theme of the conference from a diachronic perspective, employing a variety of methodological approaches.

In light of the ongoing situation in Sudan, particular emphasis will be placed on safeguarding and conserving cultural heritage, along with related initiatives and projects.

Please note that it is mandatory for all participants to register for the conference in order gain access. Online registration is now open, for details see https://nubianstudies2026.de/tickets/. Colleagues from Sudan and Egypt are entitled to complimentary tickets (free of charge). Due to the ongoing situation in Sudan, the conference will be a hybrid event.

We’re really looking forward to meeting all of you who are interested in Nubia and Sudan in Munich!